The Unexpected Champion

Before he tuned Kenny Roberts to three world titles, Kel Carruthers gave Benelli its greatest glory

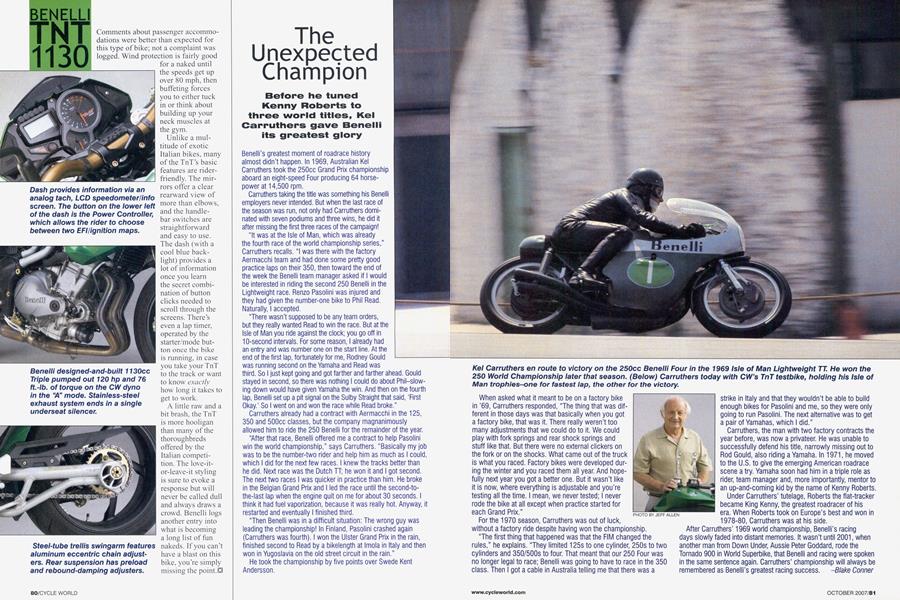

Benelli's greatest moment of roadrace history almost didn't happen. In 1969, Australian Kel Carruthers took the 250cc Grand Prix championship aboard an eight-speed Four producing 64 horse-power at 14,500 rpm.

Carruthers taking the title was something his Benelli employers never intended. But when the last race of the season was run, not only had Carruthers dominated with seven podiums and three wins, he did it after missing the first three races of the campaign!

“It was at the Isle of Man, which was already the fourth race of the world championship series,”

Carruthers recalls. “I was there with the factory Aermacchi team and had done some pretty good practice laps on their 350, then toward the end of the week the Benelli team manager asked if I would be interested in riding the second 250 Benelli in the Lightweight race. Renzo Pasolini was injured and they had given the number-one bike to Phil Read.

Naturally, I accepted.

“There wasn’t supposed to be any team orders, but they really wanted Read to win the race. But at the Isle of Man you ride against the clock; you go off in 10-second intervals. For some reason, I already had an entry and was number one on the start line. At the end of the first lap, fortunately for me, Rodney Gould was running second on the Yamaha and Read was

third. So I just kept going and got farther and farther ahead. Gould stayed in second, so there was nothing I could do about PhiUslowing down would have given Yamaha the win. And then on the fourth lap, Benelli set up a pit signal on the Sulby Straight that said, ‘First Okay.’ So I went on and won the race while Read broke.”

Carruthers already had a contract with Aermacchi in the 125, 350 and 500cc classes, but the company magnanimously allowed him to ride the 250 Benelli for the remainder of the year.

“After that race, Benelli offered me a contract to help Pasolini win the world championship,” says Carruthers. “Basically my job was to be the number-two rider and help him as much as I could, which I did for the next few races. I knew the tracks better than he did. Next race was the Dutch TT; he won it and I got second. The next two races I was quicker in practice than him. He broke in the Belgian Grand Prix and I led the race until the second-tothe-last lap when the engine quit on me for about 30 seconds. I think it had fuel vaporization, because it was really hot. Anyway, it restarted and eventually I finished third.

“Then Benelli was in a difficult situation: The wrong guy was leading the championship! In Finland, Pasolini crashed again (Carruthers was fourth). I won the Ulster Grand Prix in the rain, finished second to Read by a bikelength at Imola in Italy and then won in Yugoslavia on the old street circuit in the rain.”

He took the championship by five points over Swede Kent Andersson.

When asked what it meant to be on a factory bike in ’69, Carruthers responded, “The thing that was different in those days was that basically when you got a factory bike, that was it. There really weren’t too many adjustments that we could do to it. We could play with fork springs and rear shock springs and stuff like that. But there were no external clickers on the fork or on the shocks. What came out of the truck is what you raced. Factory bikes were developed during the winter and you raced them all year. And hopefully next year you got a better one. But it wasn’t like it is now, where everything is adjustable and you’re testing all the time. I mean, we never tested; I never rode the bike at all except when practice started for each Grand Prix.”

For the 1970 season, Carruthers was out of luck, without a factory ride despite having won the championship.

“The first thing that happened was that the FIM changed the rules,” he explains. “They limited 125s to one cylinder, 250s to two cylinders and 350/500s to four. That meant that our 250 Four was no longer legal to race; Benelli was going to have to race in the 350 class. Then I got a cable in Australia telling me that there was a

strike in Italy and that they wouldn’t be able to build enough bikes for Pasolini and me, so they were only going to run Pasolini. The next alternative was to get a pair of Yamahas, which I did.”

Carruthers, the man with two factory contracts the year before, was now a privateer. He was unable to successfully defend his title, narrowly missing out to Rod Gould, also riding a Yamaha. In 1971, he moved to the U.S. to give the emerging American roadrace scene a try. Yamaha soon had him in a triple role as rider, team manager and, more importantly, mentor to an up-and-coming kid by the name of Kenny Roberts.

Under Carruthers’ tutelage, Roberts the flat-tracker became King Kenny, the greatest roadracer of his era. When Roberts took on Europe’s best and won in 1978-80, Carruthers was at his side.

After Carruthers’ 1969 world championship, Benelli’s racing days slowly faded into distant memories. It wasn’t until 2001, when another man from Down Under, Aussie Peter Goddard, rode the Tornado 900 in World Superbike, that Benelli and racing were spoken in the same sentence again. Carruthers’ championship will always be remembered as Benelli’s greatest racing success. -Blake Conner

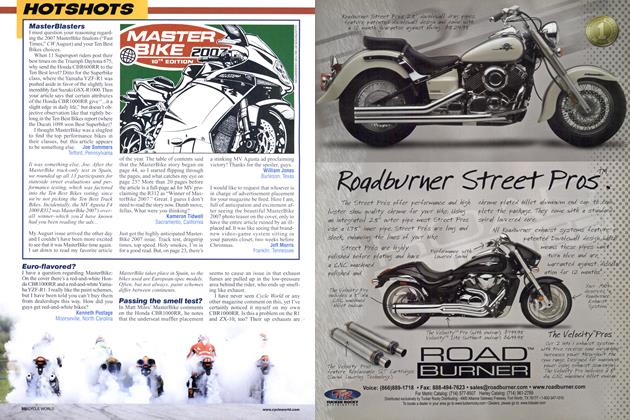

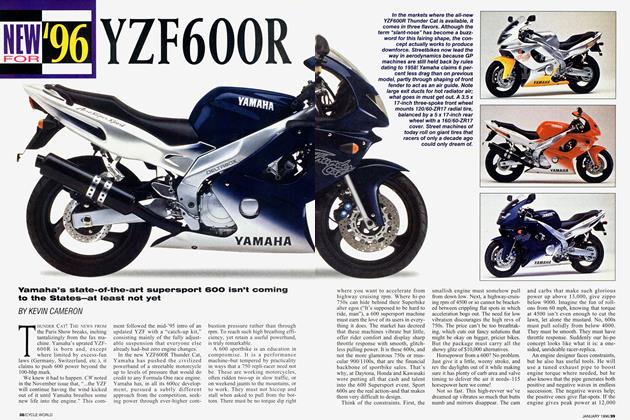

BENELLI TNT 1130

SPECIFICATIONS

$15,499

EDITORS' NOTES

THERE IS SOMETHING ENTICING ABOUT naked bikes. I don’t know if it’s the upright, commanding riding position, the hooligan image or the raw appearance of their exposed mechanicals. Something, however, always makes me want to act a little irresponsible on them. The Benelli is no exception. This Italian Triple has all the elements of an Open-class hell-raiser. The torquey

engine provides more than enough thrust to get you into trouble, while the competent chassis always makes ripping down a twisty road exhilarating.

This Benelli isn’t for everyone, because of its expensive price tag and basic components. But, those looking for something that stands out, well, the TnT could fit the bill perfectly. It lacks the polish of Japanese, Brit and other Italian nakeds, but offers a lot of fun, accessible performance and its unique, look-at-me styling virtually guarantees you’ll be the only TnT rider at your Sunday hangout.

-Blake Conner

WHILE IT STANDS THAT UNSIGHTLY LIES in the eye of the beholder, if you’re asking me, the Benelli TnT offers another shard of naked proof that certain streetfighter styling elements are best viewed with the lights turned off. Ducati literally created a monster, so to speak, with others in the naked niche trying to emulate or upstage the original

Benelli takes this clipped-tail trend to a head with its curious side-radiator placement and use of stylized cooling fans that look as though they would be at home on a computer gaming graphics card. Or was that just a computer virus in the EFI ECU?

Still, given a blind road test, I found the TnT’s nimble chassis and gutsy engine a blast to ride. In many ways it feels like a Triumph Triple stuffed into an MV Brutale chassis-albeit with a level of execution and refinement more akin to an MZ. -Don Canet, Road Test Editor

THERE IS EVERY REASON I SHOULD LOVE this motorcycle. I have obsessed about Benelli’s ’70s-era six-cylinder. I owned a 1976 Laverda Triple, the Italian spiritual father of this 1130cc TnT if ever there was one. I rode our long-term MV Agusta Brutale 750 everywhere and loved it at least 80 percent of the time. But the Green Machine just doesn’t do it for me.

Was it the years of anticipation brought on by the previous aborted Benelli importation attempts? Was it the notsorted engine management? The high price tag and almost non-adjustable suspension? The way the headlight turns off when the cooling fans kick on at idle? The clunky transmission? Yes.

It is still a pretty cool bike that goes fast, handles well and looks...okay, two outta three ain’t bad! But until refinement is improved, I’d have to go Triumph Speed Triple or Brutale 91 OR. Still, I’ll make my final decision after we get a new Tornado superbike. -Mark Hoyer, Executive Editor