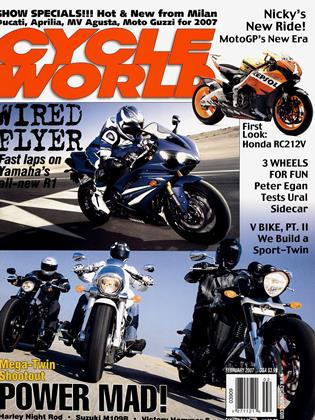

Flying on the ground

LEANINGS

LATE AUTUMN IS USUALLY THE BEST TIME for riding in the upper Midwest—dry, clear and sunny. It’s cool enough to enjoy wearing a leather jacket, but not so cold that great sheets of ice cover the North American continent and drive our local mastodon herds relentlessly south. It’s a time of ideal balance.

Not this year, though.

October was pretty much a washout for riding. Granted, we had a beautiful first weekend for the Slimey Crud Motorcycle Gang’s fall Café Racer Run-about 1000 bikes showed up-but after that things went downhill fast.

On Monday morning, low clouds moved in like an armored division and brought with them an endless convoy of bad weather-wind, cold, freezing rain and snow showers. Nearly four unbroken weeks of it. I parked my bike and, until yesterday, didn’t ride at all. Pretty grim.

Luckily, I found a novel way to make it through those dark and difficult weeks without giving up my usual quota of banked turns, skids, slips, hair-raising miscalculations and grateful homecomings.

I took flying lessons.

Yes, after a 15-year absence from flying, I’d decided to get back into it, to see if I could be taught to fly again and update my license. I took an FAA physical (alarmingly thorough, it seems, when you’re 58) and signed up for flying lessons at a place called Morey Field in Middleton, Wisconsin. My instructor, an unflappably calm and patient man named Richard Morey, is the grandson of the airport’s founder. A thirdgeneration flight instructor. His grandfather, an aviation pioneer and barnstormer, flew with Lindbergh.

It may have been too cold for riding-at least by my exacting and self-indulgent standardsbut not for flying. Airplanes don’t mind a little sleet or dry snow blowing around. They have heaters. So I flew twice a week for four weeks and finally finished up last Tuesday.

On this final lesson, we flew to nearby Sauk Prairie Airport so we could take advantage of the fierce crosswinds and see what I was made of. Never a good idea, but we somehow survived my crosswind landings without serious injury. So Rich-in a mood of life-affirming gratitude, no doubt-signed off my ancient

and crumbling log book (first entry, 1964). I was good to go. A pilot again.

And the next day, as if by magic, the bad weather skulked off to the east, high pressure moved in and our classic fall riding weather returned. It was a sunny 65 degrees yesterday, and I took my big KTM 950 out for a good backroad flog through the russet-colored hills with leaves swirling across the road and the dry smell of corn-harvester dust in the air. Carved pumpkins grinned at me from farm porches. Glorious stuff.

And, while riding again at long last, inevitable comparisons crept into my partially trained journalistic brain and I started thinking how closely related motorcycling is to flying.

Okay, they aren’t exactly the same. When you climb out of a Cessna after an hour of crosswind landings, driving anything on the highway at moderate speed seems absurdly easy, and you wonder briefly how anyone ever manages to have an accident-especially in a car.

There are no critical instruments to scan (other than your speedometer, if you so choose). No rate of climb or stall speed to worry about. Your altitude and heading are pre-determined by the road. You don’t have to radio ahead to Barnes & Noble and tell them you’re coming into the parking lot from the west on a heading of zero-niner-zero. There are no other vehicles above or below the road surface. If your engine quits, you pull over.

Another difference is that flying-once you’ve mastered the basic motor skills— is more of a cognitive process than riding and less of an athletic act. You always have to think about where you’re going, where you’ll be 20 minutes from now and how you’re going to make it all happen. The actual steering is not so crucial, except in landing.

Riding, particularly dirt riding, roadracing and fast backroad riding, is more physical and immediate. Your plans are much shorter in range and duration, corrections more frequent and imperative. Expletives of doom arrive with greater regularity.

But the two sports are still related. You tilt the horizon and forces act through your own personal vertical axis. Bank, accelerate, zoom. Grin. Your inner ear is hard at work, as it is nowhere else. In full flight, with either bikes or planes, all your senses are engaged and you become hyper-alert.

Maybe that’s the link: The thing flying and motorcycling have most in common is that you simply must pay attention. Your life depends on it. Both sports, you might say, are naturally riveting.

Of course, the same may be said of mountain climbing, whitewater canoeing, sky diving, bicycle racing, downhill skiing and mountain biking. (Notice how all these sports involve a rapid elevation change. A form of falling, as it were, skillfully arrested.)

In any case, it’s that paying attention thing I like best.

Winston Churchill once remarked that nothing is more exhilarating than to be shot at and missed. Well, pilots and motorcyclists are shot at quite often, figuratively speaking, and called upon to arrange their own near misses.

Which is a good thing, in my opinion. Life is full of perfectly nice activities that don’t require this kind of concentration, but most of them seem to me only halfinteresting.

As I’ve discovered at many parties and social gatherings over the years, I’m never really comfortable-or completely awakearound people who are unacquainted with the invigorating joys of mild panic. □

Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue