A Keen Life

RACE WATCH

From Ascot hero to short-track innovator, Neil Keen led the way

CHUCK WEBER

THE NOISE WAS DEAFENING AS THE RIDERS CHARGED TOWARD the first corner. Forced off the racing line, Neil Keen slipped from near the front back to ninth. After 14 laps, he regained his rhythm and worked his way through the pack to second place. Only the great Carroll Resweber lay ahead. The reigning AMA Grand National Champion had a lead the length of the front straightaway, but Keen was not about to be denied a national win on his home turf. One lap later at the end of the backstretch, Keen made his move. He passed Resweber on the inside and went on to win the 1961 Ascot 8-Mile National by a clear margin. If was the highlight of a most remarkable season for the 26-year-old BSA rider, who had won 19 of the first 24 races and an incredible 11 straight on the legendary Los Angeles track.

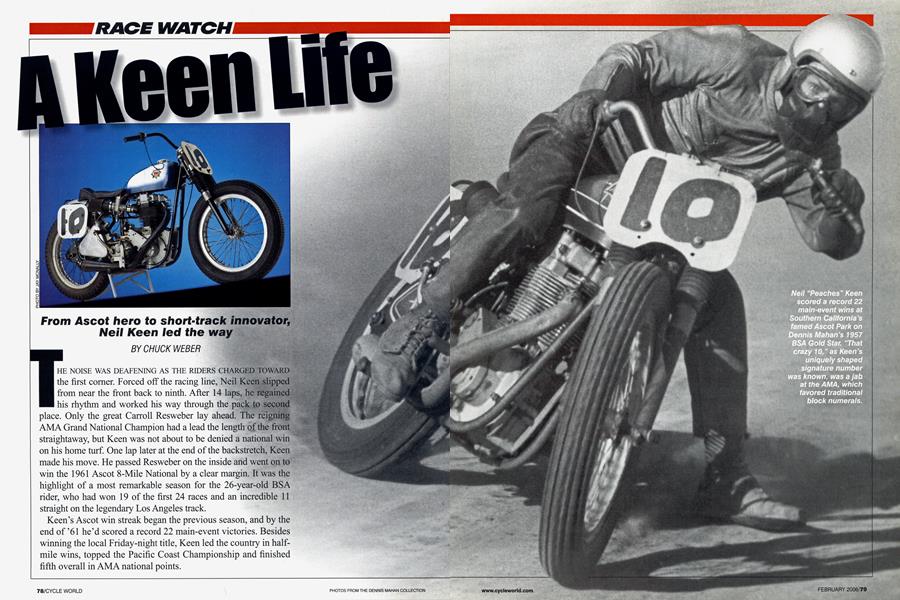

Keen’s Ascot win streak began the previous season, and by the end of ’61 he’d scored a record 22 main-event victories. Besides winning the local Friday-night title, Keen led the country in halfmile wins, topped the Pacific Coast Championship and finished fifth overall in AMA national points.

Previously known as L.A. Speedway, the half-mile oval was leased to promoter J.C. Agajanian in 1959 and renamed Ascot Park. Under Agajanian’s stewardship, the track flourished and saw some of the greatest motorcycle racing ever. National-caliber riders like Sammy Tanner, AÍ Gunter and Joe Leonard attracted sellout crowds, and the racing surface offered incredible traction. Keen recalls it as being “not a groove or a cushion,” but offering a variety of racing lines.

These were the days before flat-trackers wore brakes. “At Ascot, you didn’t countersteer through the comer in a typical flat-track slide,” Keen describes. “You came into the comer so hard that the front wheel would plow. That would help slow you down.” Using this method, Keen and competition would barrel around the track three abreast, lap after lap. Fearless Harley-Davidson factory rider Bart Markel was amazed by this on his first visit to the track. He called the Ascot regulars “the hardest riding bunch of guys I ever saw.”

To win at Ascot, Keen had to outrun not only Harley riders Markel, Leonard and Resweber, but also Triumph-mounted Darrell Dovel and Tanner, as well as fellow members of the famed “BSA Wrecking Crew”-Gunter, Jack O’Brien and Stuart Morley. Keen admits that he had to mentally prepare for the Friday night races on Wednesday, psyching himself up to compete not only against the other riders but the track itself. He was also witness to the bloody reputation Ascot earned during this time, with 24 riders killed in a three-year period, several of whom were his close friends.

Keen’s racing career began when he started attending races in Georgia (hence the nickname, “Peaches”), where he lived with his mother. He caught the competition bug but was told that the “real racing” was in California. So in 1952, the 18-yearold packed up and moved to Pasadena. He began racing professionally two years later, gaining experience on tracks like Los Angeles Speedway and nearby Gardena Stadium. Racing just twice in ’54, Keen struggled, but the following year he finally won an event in Tulare.

With his racing skills constantly improving, Keen earned his Expert license in 1957. By this time, he knew what it took to make a bike handle well and soon became an innovator in dirt-track chassis and frame design. A gifted mechanic, Keen also earned a reputation for his engine-building skills. In addition to racing, he began sponsoring other riders, including fellow Ascot star George Everett. Sadly, Everett was killed at Ascot in 1959 during his first ride on a factory Triumph.

That tragedy brought Keen to a turning point. He knew that to become a highcaliber racer, he needed his own tuner, which would allow him to concentrate fully on the track. He found the man he was looking for in Dennis Mahan. Just 18 years old, Mahan already had a reputation as a brilliant engine developer and master mechanic, and he just happened to be looking for a hard-charging rider to put on his own BSA. The pair would become one of the most successful rider-and-tuner combinations ever and develop a friendship that continues to this day.

With Mahan spinning the wrenches, Keen started winning, earning the national #10 plate during the 1959 season. Their confidence quickly grew, culminating in the highly successful 1960 and record-breaking ’61 seasons. For years after, fans would immediately recognize the uniquely shaped “0” on Keen’s numberplates.

Mahan remembers the 1961 Ascot season as something special. “Every rider who made the main event was capable of winning, but Neil and I just knew we were going to win,” he says. “Our confidence was just so high, mine in Neil’s riding and his in the bike.”

With Keen at the top of his skills, Mahan played mind games with the other riders and tuners. Some were subtle, like placing a large stack of the preferred but difficult-to-get Firestone tires in his and Keen’s pit area. Other tricks involved installing complicated hoses, batteries and other parts on the bike, which made it appear as though Mahan was trying some slick new innovation. In reality, the parts weren’t functional.

For the start of the 1962 Ascot season, H-D race-team boss Dick O’Brien offered Keen the latest KR factory racer. Keen and Mahan jumped at the chance but struggled with the bike. After finishing poorly in the first eight races, they returned it, along with all the spare parts they had been given. O’Brien later noted that this was the only time anyone had ever returned all of his equipment. Back on his trusty Gold Star, Keen regrouped to win several races.

That same season, Keen and Mahan obtained the first Yamaha TD1 roadracer. Along with Gunter, they became the factory’s first U.S. roadracing team. Although he enjoyed pavement racing, Keen struggled at it. “I was no good at all that slowing down and speeding up again,” he says.

In 1963, the season started great with two wins at Ascot, but then Keen crashed heavily and broke his arm and shoulder after making contact with a fallen rider. He recovered from the injuries, but found himself burned out on the weekly Ascot grind. The stress to remain a winner was overwhelming, and he needed a change.

On his earlier travels to AMA nationals in other parts of the country, Keen had enjoyed the racing stops in the Midwest. Of the Kansas county-fair circuit, Keen says, “You could get up in the morning, have breakfast in one of the small-town diners, take in the fair and relax until the evening races.”

With Mahan’s help, Keen knew he was good enough to compete for national wins, but that factory-backed riders like Markei, Dick Mann, Fred Nix and George Roeder were more likely to come out on top. Midwestern fair circuits suited him just fine.

In 1965, Keen, now sponsored by legendary dealer John Lund, moved to Decatur, Illinois. His strategy was to ride the AMA events that were within a reasonable distance and compete on fair circuits that were closer to home. Not only were there plenty of half-miles to ride, but shorttrack racing was catching on strong. Racing was fun again.

Keen loved the excitement that the smaller bikes racing on short-tracks provided. Many factory riders thought faircircuit racing and short-tracks were beneath them, but Keen thrived on such events. “Short-track racing is like manure,” he says. “Everybody knows it will do their garden good, but nobody wants to put their hand in it.”

Winning, however, was far from easy. Mann, Markel and the rest would still show up at these events without notice, making for a tough night’s work. Still, Keen loved the competition and enjoyed the variety of tracks that the Midwest offered. Moreover, by supplementing his busy weekend racing schedule with weekly short-tracks at Granite City, Illinois, on Tuesday, Santa Fe Speedway just outside of Chicago on Wednesday and Auto City, Michigan, on Friday, he could make a good living.

In 1968, Keen and Mann began racing Bultacos provided by Lund, and the three of them made the two-strokes competitive. Early seizures and the questionable legality of compression releases were overcome, and Bultacos quickly became the bike of choice in short-track competition. Their success led to a nearly universal switch from fourto two-stroke machinery by the start of the 1969 season.

That year saw Keen make several changes. Now riding BSAs and Yamahas for St. Louis-area dealer Carl Donelson, he moved to Missouri and with Mahan’s > tuning skills, turned the Yamaha DTI trail-bike engine into a competitive shorttracker. A new age of technology had begun. No longer could riders simply strip a streetbike and attempt to be competitive. With the advent of special frames, wheels, tires and other components, a purposebuilt flat-tracker was necessary for anyone taking his racing seriously. Keen, seeing the opportunity to fulfill a real need, began his own successful flat-track accessory business, Neil Keen Performance, which he continues to operate today in Wentzville, Missouri.

Keen carried on racing competitively until 1974 when a broken shoulder ended his season prematurely. He was 40 years old and felt he was losing his edge. Even though he had won 24 features the previous season, Keen was having trouble winning “bare knuckles.” He had always raced to win and was not satisfied with anything less. By the end of the season, he made the decision to retire. There was no fanfare, no statement, no farewell tour. He simply stepped out of the limelight.

Keen’s racing career spanned 21 years, unusually long for a rider of his era. He made more than 200 starts during the Ascot years alone, and in one season traveled to 130 events, often solo. He earned his living racing, and won a staggering 354 features. And he did it not with factory sponsorship, but with the help of passionate friends. He fully acknowledges the role that Mahan (who went on to work for Yamaha, Can-Am and Kawasaki, and is still active in the powersports industry with K&N) played in his success.

“Dennis was never too tired, he never gave up, he always knew what to say and when to say nothing,” Keen says. “I won a lot of races that I would not have won without my blood-brother Dennis at my side.”

Asked about Keen’s come-from-behind win at Ascot in 1961, Resweber says, “There was no stopping Neil that night. He was in charge.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontWorld's Fastest Indian

February 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBeemer Report Card, Summer Semester

February 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUntying Knots

February 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2006 -

Roundup

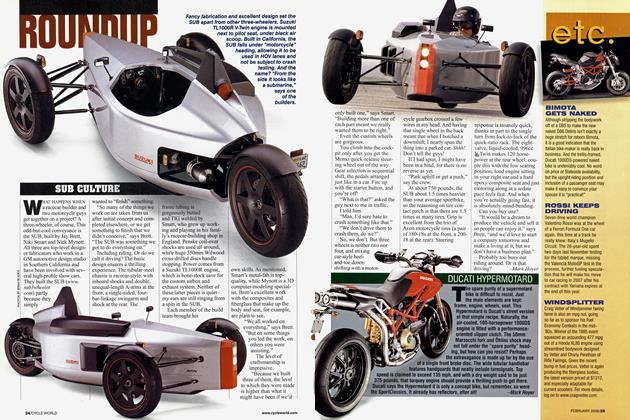

RoundupSub Culture

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

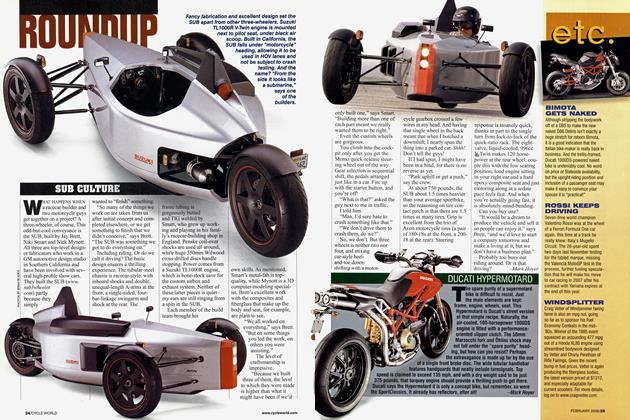

RoundupDucati Hypermotard

February 2006 By Mark Hoyer