LIFE AND DEATH IN DAKAR

RACE WATCH

Triumph through tragedy in Africa

MATTHEW MILES

THE PREMISE BEHIND RALLY RACING IS SIMPLE: GET yourself and your motorcycle from Point A to Point B as quickly and efficiently as possible. Problem is, in Dakar, nothing is simple.

Established in 1979, the Dakar Rally is the toughest offroad event in the world. Crossing more than 5500 miles of largely uninhabitable terrain in just 17 days, this year's race was arguably the most dangerous, the most difficult and, following the deaths of Spain's Jose Manuel Perez and two-time winner Fabrizio Meoni, the most tragic in the event's 27-year history.

Perez and Meoni died within a day of each other, the former from injuries sustained two days earlier, and the latter during a special test in Mauritania. After a oneday break, the rally carried on because, according to Meoni’s teammates, “That’s what Fabrizio would have wanted.”

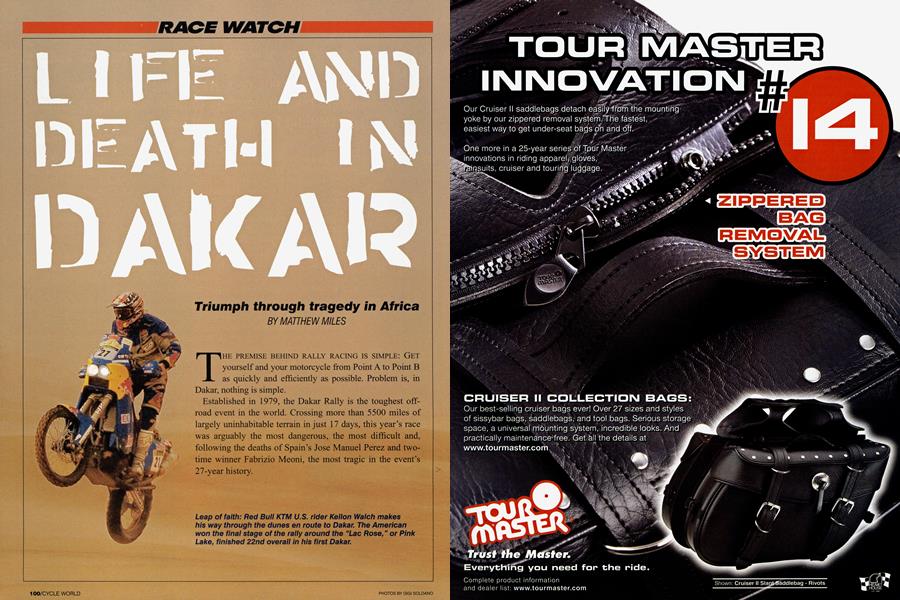

This year, five Americans made it to Dakar. Three of them-48-year-old Scot Harden and 20-something rally rookies Chris Blais and Kellon Walch-rode for the fast-emerging Red Bull KTM U.S. effort. Charlie and Dave Rauseo were true privateers. Charlie, 38, back after a failed attempt in 2004, had wanted to race Dakar for 25 years (“Since before Kellon was alive”). Dave, 39, has the perfect attitude for Dakar. “If you hit him in the head with a 2x4,” laughs Charlie, “he’d just smile and say how happy he was that it didn’t have a nail in it.” To raise the $100K in cash and product needed for the event, the brothers hosted XR100 races, sold T-shirts and collected sponsors.

Harden, a three-time Baja 1000 champion, made his return to international rallying last year after a 16-year hiatus. In 2004, as a stand-in for the injured Casey McCoy, he retired with a broken ankle. This year, despite another injury, he finished. “What brought me back to Dakar was the simple fact that I didn't see the finish line last year," he says.

Harden is not at ease with Dakar. Going into the event this past January, his greatest concern was being killed. He feared the inevitable suffering and the possibility of letting his teammates down, but mostly, he didn't want to die on a motorcycle in the middle of the desert.

Age and experience can be an asset in Dakar. Meoni, who was 48 at the time of his death, was at the top of his game. He knew when to go fast and when to slow down. He knew how to care for himself and his motorcycle. But older riders don't always know their breaking points.

"If fear starts to outweigh the joy, you become para lyzed-you don't do the things you know you can do," says Harden. "Then it becomes harder to move forward."

j~)i vvaiu. Blais and Waich didn't know what they didn't know. Young, blazing-fast desert racers, the pair (along with alternate Andy Grider) survived an intense, televised rider search to win spots on the team. "Chris and I didn't have a clue about Dakar," admits Waich. "We'd heard some stories from (former C WOff-Road Editor) Jimmy Lewis, but we figured, `Whatever.' Turns out, all the stories were all true!"

Waich assumed Dakar would be simi tar to the Baja 1000 or other desert races. He was nervous about the dunes and navigation aspects of the rally but at the end of the day, "You're riding a motor cycle, right?"

According to Harden, navigation is 20 percent of the Dakar equation. Ten or 15 years ago, he says, you took out a com pass, found a point on the horizon, rode to that point and started all over again.

Now, with the "safety corridor" pro grammed into the mandatory, dash mounted global positioning system, in addition to the all-important road book, finding your way on the trail is easier. To their credit, Blais and Walch adapted quickly. "All young Americans are used to video games," says Harden, "and Dakar is kind of like a big video game."

In some ways, GPS has softened the sport. In year's past, to make time, a rider might short-cut the course at the risk of getting lost-or blown up by a land mine. Now, if you leave the safety corridor, which measures 2 miles on each side of the ideal line, you get penalized. "That's why guys stack up at the front now," explains Harden. "You can't make a break. Meom was very vocal about it this year."

During the first couple of days, Watch was on a high. He had done well in the initial special tests, placing in the top 10 both days. Then, on the fourth day, he crashed big time. He hit a ditch, flew over the handlebar and smacked his head. "I knew I had a concussion because I was sick to my stomach," he says. "After I got back on the bike, I crashed again because I didn't have any brakes."

Two days later, Waich flew off the back side of a dune. For miles, the mountains of sand had been virtually identical. This par ticular dune, however, was different. "I rolled over the top and dropped into a big bowl," he remembers. "I hit the other side of the dune and my face went straight into the road book. During the rally, my life passed before my eyes twice, and that was one of them. I actually had time to think about crashing."

Gettmg out was difficult. Walch's KTM 660 was buried in sand at the bottom of the bowl. "If the bike is buried, you have to tip it over," he explains. "I did that a few times.

It wasn’t a huge bowl, so once I got some speed, I was able to ride it out.”

Extricating yourself from energy-sap ping, potentially complicated predica ments is a big part of Dakar. As 1-larden points out, once you roll off the line each morning, it'sjust you and the motorcycle. "It's nice at the end of the day to see the smiling faces of your support crew, but the real work is done out on the course. No one can save you but yourself," he says. With the exception of the two "mara thon" stages, riders met up with their sup port crews each night. Harden, Blais and Walch enjoyed a structured existence, but sleeping on the ground in the middle of a sandstorm is not easy. "It was still a shock to the system," explains Harden. "We were in an extremely demanding en vironment that was in a constant state of flux. Information coming from the organization was changing by the minute. Conditions on the course were changing. We had to adapt." Life was tougher for the Rauseos, who brought along their own mech anic, Mike Krynock, and chase-truck driver, Zoli Csik. "They were definitely the superstars,” Charlie says of the factory riders. “We were just covered in dust and dirt the whole time.”

Sleeping in the bivouac, with all the noise created by the impact wrenches and generators, was easier than it sounds. “At the end of the day, you’re so wipedout, going to bed is no problem,” Walch says. “You actually look forward to it during the day.”

Event organizer ASO provides sustenance for the entire rally. “The food was first-class,” says Harden. “There was plenty of meat, pasta, vegetables, wine, nice desserts and lots of bottled water.” Blais and Walch were less complimentary. “Chris really struggled with the food,” chuckles Walch. “He ate pasta for breakfast and dinner every day. I pretty much lived on bread and water. They had eggs, but the French don’t cook them right; they’re too runny.”

One evening, the catering tent caught fire. Harden, Blais and Walch had taken a taxi to a village for a shower, and when they returned, everything was dark-the tent was gone! Harden figured they were disoriented from what turned out to be the worst sandstorm the area had seen in 35 years. In reality, they had just missed a raging firestorm with flames leaping 40 feet into the night sky. In an hour, however, order was restored and meals were once again being served. "We had trouble keeping sand out of our food that night," Harden laughs.

The early morning transfers-or liaisonsranged in distance from 5 to 570 miles, and were often as difficult as the racing. “I dreaded the liaisons,” admits Harden. “You get up in the middle of the night, get on the bike and are frozen-literally frozen-for three or four or nine hours.” Adds Walch, “It’s hard to stay motivated. You’re out in the middle of nowhere, you can’t see any-

thing, especially during a sandstorm, and your mind starts to wander. That’s when things can get bad.”

Arguably the toughest day was the seventh stage between Zouerat and Tichit. Even overall winner Cyril Despres, who conquered the stage in 10 Y hours, was critical: “The organization said there was 37 miles of camel grass, but in fact we did maybe 150 miles of camel grass.”

“I’ll never forget that day as long as I live,” adds Harden. “Camel grass is your worst nightmare. It’s like riding the worst supercross whoops in the world on a bike that weighs 500 pounds.”

Common to southern Asia and northern Africa, camel grass is like pebbling on a basketball. Thousands upon thousands of rock-solid, tuft-topped mounds, laid out on a carpet of deep, soft sand, dot the desert landscape. You can’t ride over them, so you have to ride around them. And because you’re stuck in first or second gear, you can’t carry any speed, so you have to fight the sand.

Eighty percent of the field ran out of gas that day and had to camp in the desert. “Luckily for me, Giovanni Sala from the Repsol KTM team helped me get some more gas,” says Walch. “The organization wasn’t going to give us any more, and we weren’t going to make it.”

Charlie Rauseo topped up twice, too. “You do what you have to do,” he shrugs. Once the sun went down, it was impossible to ride fast, so he just kept plugging along through the camel grass all night long. He made it into camp at 7 a.m., two hours before the scheduled start of stage eight. “I didn’t know they were going to cancel the stage. I figured I would have enough time to get a nap, eat some breakfast and do a little work on my bike. All those guys camping out in the desert, I figured they were going to miss their start times. I couldn’t understand how they could stop. The goal is to finish.

“My brother broke his leg,” continues Rauseo. “Had he been a quitter, he would have been on a plane home. I think a lot of people who quit the rally could have continued, but they found a reason to stop. I don’t blame them for quitting; it was extremely difficult.”

Finishing the rally tmly is a feat in and of itself. Frenchman Patrick Zaniroli was responsible for the race route, which Harden says has become too difficult. “The last two years were exceptionally

hard. It went beyond sporting, and Zaniroli is getting the axe because of it.”

This past April, Zaniroli announced he was leaving ASO after 13 years with the organization, but that his departure was “my initiative.”

Charlie Rauseo feels the race should be more difficult. “There are a lot of proposals for next year to slow things down.

I disagree with that. If everyone can do it, Dakar becomes an amusement-park ride. No one dies on a roller coaster.

“Danger is part of the rally,” he maintains. “There were plenty of places where I could have gone faster. But if I would have fallen and hurt my bike or myself, I wouldn’t have finished. At one point, I rode all by myself for 2/4 hours. I didn’t see a single track. Had I fallen there, they may not have found me for a long time. You have a locator beacon, but you have to be conscious to set it off.”

Despite the difficult conditions and constant unknowns, Dakar is not all doom and gloom. “I was giggling the whole time,” Rauseo says. “You get to ride a dirtbike in a beautiful part of the world, how bad can it be?” Walch agrees. “There’s nothing like Dakar, I can tell you that. It was a neat experience, and I’ll never forget it for the rest of my life.”

“Most guys ride motorcycles for the sporting side of it,” adds Harden. “And there’s an element of that in Dakar. But there’s so much more to it. Karl Wallenda, the greatest high-wire man in the world, had a great saying: ‘Life is being on the wire. Everything else is just waiting.’ That’s why you race Dakar.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

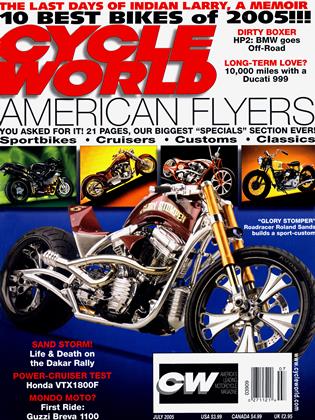

Up FrontGeneration Ten Best

July 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsInfamous Drawer of Useless Dead Weight

July 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDuty Cycle

July 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2005 -

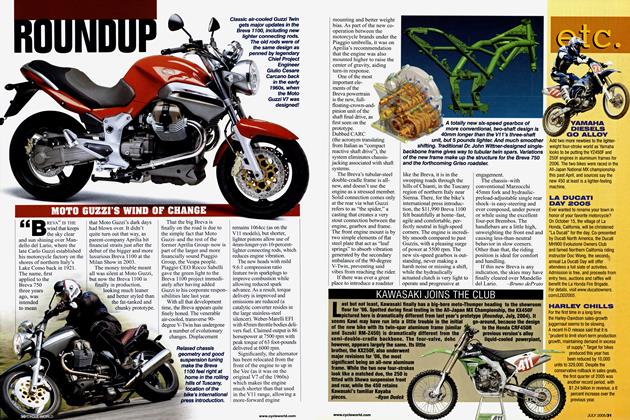

Roundup

RoundupMoto Guzzi's Wind of Change

July 2005 By Bruno Deprato -

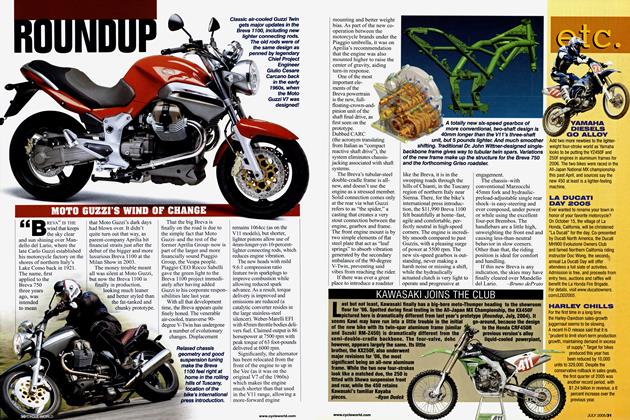

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Joins the Club

July 2005 By Ryan Dudek