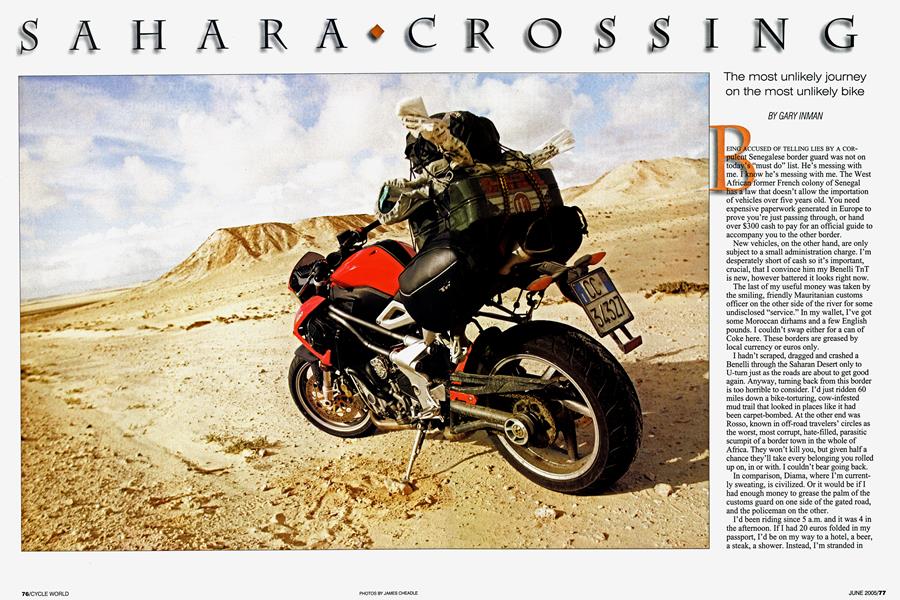

SAHARA CROSSING

The most unlikely journey on the most unlikely bike

GARY INMAN

BEING ACCCUSED OF TELLING LIES BY A COR-

Senegalese border guard was not on today’s “must do” list. He’s messing with me. I know he’s messing with me. The West African former French colony of Senegal aw that doesn’t allow the importation of vehicles over five years old. You need expensive paperwork generated in Europe to prove you’re just passing through, or hand over $300 cash to pay for an official guide to accompany you to the other border.

New vehicles, on the other hand, are only subject to a small administration charge. I’m desperately short of cash so it’s important, crucial, that I convince him my Benelli TnT is new, however battered it looks right now.

The last of my useful money was taken by the smiling, friendly Mauritanian customs officer on the other side of the river for some undisclosed “service.” In my wallet, I’ve got some Moroccan dirhams and a few English pounds. I couldn’t swap either for a can of Coke here. These borders are greased by local currency or euros only.

I hadn’t scraped, dragged and crashed a Benelli through the Saharan Desert only to U-turn just as the roads are about to get good again. Anyway, turning back from this border is too horrible to consider. I’d just ridden 60 miles down a bike-torturing, cow-infested mud trail that looked in places like it had been carpet-bombed. At the other end was Rosso, ¿10wn in off-road travelers’ circles as the worst, most corrupt, hate-filled, parasitic scumpit of a border town in the whole of Africa. They won’t kill you, but given half a chance they’ll take every belonging you rolled up on, in or with. I couldn’t bear going back.

In comparison, Diama, where I’m currently sweating, is civilized. Or it would be if I had enough money to grease the palm of the customs guard on one side of the gated road, and the policeman on the other.

I’d been riding since 5 a.m. and it was 4 in the afternoon. If I had 20 euros folded in my passport, I’d be on my way to a hotel, a beer, a steak, a shower. Instead, I’m stranded in the between-borders No Man’s Land, trying to get into Senegal. I show the guard my Benelli’s Italian registration document with the date “May 19,

2004” clearly marked on it.

“This is fake,” the guard sneers, nothing but thinly veiled loathing showing on his face. I wasn’t expecting that. He looks like Idi Amin, the former Ugandan dictator with cannibalistic tendencies. He’s a big man.

A foot taller than me, and a good 70 pounds heavier. He’s the fattest man I’ve seen for more than 1500 miles.

Extortion is his business and business, it appears, is good.

I walk toward the filthy, dog-tired bike, with my filthy, dog-tired boots kicking up sandy dust. “Regarder” or “look” I say in my bad French while putting the key in the ignition and flicking it on. The tach and temperature needles jolt into life and do a synchronized sweep from left to right and back again. The digital speedometer shows signs of life and the TnT’s total mileage is indicated. Six thousand and change.

Was it the needles’ dance or the mileage figure that convinces him the bike is new? No matter; the subject is closed. He’ll have to extort some other poor sap today.

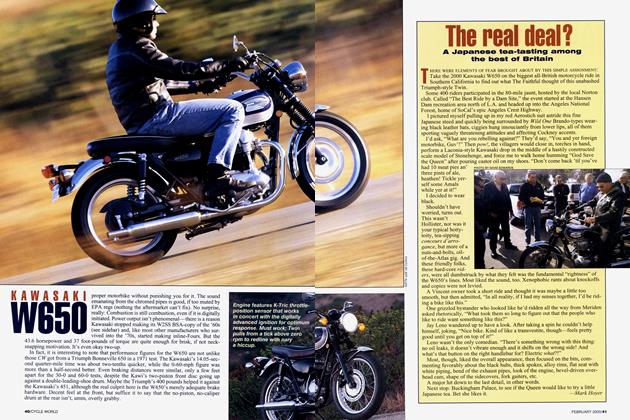

s transition into Senegal is just one uncomfortable, unforttable experience in a trip full of them. Nine days ago I as in Malaga, Southzern Spain. I’d flown from England collect a used but still-fresh Benelli TnT 1130 to ride rough the Sahara Desert to evocative Dakar, the capital of Senegal and finishing point of the famed rally.

Back on that Monday afternoon, when I couldn’t stop smiling, I had no idea how hard the trip would be on me or the bike. I knew it was potentially dangerous and pretty foolhardy, but I had absolutely no inkling of how extreme it would be, especially for a guy who’s never done anything like this kind of touring before. The bike’s unsuitability didn’t bother me, because “experienced” travelers told me the route I had chosen through the huge expanse of the Sahara was the “easy” way and it suited me to believe them.

I was drinking deep on a cocktail of naivety, lack of research and good, old-fashioned, misplaced confidence.

A cocktail few others shared. Upon hearing my plan, one friend asked where he should send the flowers after it all went wrong. Close to my departure date the negative comments started to have an effect on me. I was nervous leaving home, but put on a brave face for my wife and 2-year-old son. I didn’t tell her just how far I could be away from a hospital if anything happened. I didn’t tell her about the Algerian-backed freedom fighters in Western Sahara or the Senegalese bandits. No one had forced me to do this trip; it was all my idea. But by the time I started to be concerned about safety issues I’d spent too much time and money organizing the trip to back out. I just had to hold on tight.

My first few days in Africa through Morocco were an 80mph blur of easy acclimatization. Three days of getting used to speaking bad French; to seeing whole towns walking the street in the early evenings; witnessing men skinning goats hung from trees at the roadside; hearing calls for prayer. Every sight and experience was fresh and interesting, the roads were great, if a little dusty. Touring Africa was really

no more difficult that touring Europe. Or so I thought.

Exiting Morocco bound for Mauritania was one of the more straightforward border crossings. But a group of middle-aged Frenchmen who formed an eight-strong, organized group in late-model off-road cars kept looking at my bike and sucking their teeth. They were heading back north and keep asking, “You are taking this on the piste?” with a note of incredulity tinting their query. At that point, my Benelli still looked showroom fresh and ready to cruise through Paris or Milan, not head deeper into Africa through one of the most famous and foreboding wildernesses on the planet.

“Oui,” I reply, playing it cool, wondering what the hell a “piste” looked like, and what exactly was ahead of me.

Yes, the previous 1500 miles of Morocco and the United Nationspatrolled Western Sahara had lulled me into a false sense of security. But the road ended leaving Morocco. Now it was “pistet I found out this term covers every surface from smooth dirt road to terrain that’s only slightly more worn than the virgin wilderness on either side of where you are traveling. Right here, right now, piste is a dirt, sand and rock trail.

After days of impeccable behavior while being used in its natural (asphalt) habitat, the sporty and cool TnT starts acting drunk, swerving in ruts and wheel-tracks. Not only is this the wrong place for a Benelli, it’s the wrong place for me. To this point, I’d done three days of off-road riding in my life, spread over a decade or more, and all on green lanes in Britain, where I live. Most of the memories are of humiliation and aching muscles. None of my previous experience was gained on sand or in the company of the buried, highly explosive ordinance in the form of the common minefields found here between borders.

I rode slowly, paddling with my feet when the sand was deep. I didn’t know and had no desire to find out how close to the trail the mines are buried.

As the enormity of what I’d undertaken sank in on this first little taste of dirt, I rattled around the Mauritanian border for a couple of hours. The time is filled with guides fighting over my business; requests for bribes; being befriended by a man who looked like Disney’s idea of a fat Arab and turns out-I’m told later-to be the local mafia; lying through my teeth to escape this local Don Corleone and then ending up in the frontier town of Nouadhibou, where I need to sleep for the night before heading into the real open desert the next day.

ouadhibou is terrifying. First, it’s at the end of 15 miles of eyeball-shaking trail, the likes of which, obviously, I’ve never seen before, never mind ridden a highly strung Italian streetbike down. Within the first mile I hit deep sand and whack my nuts on the sharply angled gas tank, forcing me to stop and slump into a heap. I eventually got to Nouadhibou, but it was heartbreaking to realize I had to retrace my steps the next morning to get back to the road south.

Second, what’s really spine-chilling about Nouadhibou to a motorcyclist is that it’s like Mad Max made real. The majority of the cars, and there are lots of them, have no headlight glass or windows and most look like they’ve been rolled a dozen times. Old Renaults and Mercedes give me and the Benelli baleful, dead-eyed, zombie-like stares. The trucks are relics from the Forties, full of laborers wrestling for a spot in the back. Donkeys hauling mutant carts rush everywhere and stick to the potholed roads, meaning the zombie cars take to the sandy shoulder, then swerve erratically back onto the tarmac. In among the madness, the Benelli has become invisible, and I’m waiting to be struck down. Nothing gives me an inch. I’d be safer on a donkey. I’d be safer somewhere else.

Sanctuary is a walled campsite in the center of town. It’s aimed at, and full of, European off-roaders. Cheery Dutch couples, neither of whom have boosted Gillette’s profits in

the past three months, speak of “the beauty of Timbuktu.” Three Germans in weightlifters’ baggy pants pack their huge Mercedes off-road truck in an orderly manner.

I’m the sole traveler in the campsite from England, and the only one on two wheels. Tomorrow I’ll start on the real purpose of the journey-riding a Benelli through the Sahara. Everything so far has been hors d’oeuvres.

o survive the Sahara I either need GPS or a guide. I'm so inexperienced with this kind of travel I didn’t even consider GPS. So, for the sake of survival, I hook up with two Dutch guys, Andre and Ronald, who are driving to Gambia to deliver a beaten-up Jeep to a charity. We ask the campsite owner to arrange for a local guide to visit us. Mr. Abba certainly looks the part. He's a dark-skinned Arab in his mid-50s, wearing a Bedouin's flowing, white robe and headdress. We agree on a fee of 200 euros, about $250, far more than I imagined it'd be. This covers a three day trip through the desert to Nouakchott, the capital in the south. Mr. Abba doesn't speak a word of English, but doesn't seem fazed about having the bike as part of the group, even though he took a long, close look at the 180mm-wide, virtu ally smooth sportbike rear tire.

I finally start to get really nervous. My first little taste of dirt riding to get here was close to impossible. What's the Benelli going to be like when the going gets really tough? How tough will the going really get? By 8:30 a.m., we're out of Mad Maxville and back on that

horrible road. At the beginning of the day, fresh and rested, the piste is slightly easier to deal with. It's no longer a sur prise, and I know there's a proper road of fresh, black tarmac at the end of it. But despite what I'd read before leaving, the road's not actually finished... This glorious smooth section lasts only 15 miles, then I'm back on the piste.

ling~'is hot, dusty work that demands constant concentra tioujt I want to relax at all, I have to stop. After 55 miles, the car suddenly turns right, off the piste and, without paus in&~he Sahara Desert. My mouth dries in an instant. I know 1 need to relax and just keep the front wheel pointing in the direction I want it to go and the rear will follow. I know I should try standing up. I know I should

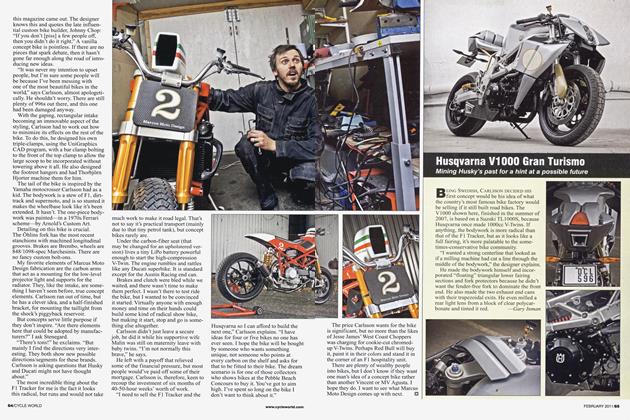

HOW TO ABUSE AN ITALIAN EXOTIC

Prepping a Benelti TnT for the desert

A Benelli TnT 1130 isn't the obvious choice for an off-road trip through Africa, but it did make for an interesting journey. Anybody can ride a KTM Adventure or BMW GS, right?

So how do you prep a TnT for Desert Duty? Benelli's own engineers carried out a surprisingly limited number of modifica tions before releasing the TnT on what has got to be the toughest test undergone by the Italian builder's stunning streethghter. The two standard side-mounted radiators were replaced with a custom set 20 percent larger, and fitted with electric fans. They also replaced the standard Dunlop D2O7RRs with D22OST sport touring tires-oh, that'Il make a big difference in the desert1 The only other "mods" were my own, namely ditching the mirrors and loosening the Allen bolts on the lever perches so they swiveled rather than snapped if/when I bailed off the bike. That was it.

If I knew what the TnT was going to be put through before I left, I never would have set off on a bike as complicated and seem ingly fragile as this. But it never let me down. I thought the clutch would give me grief, but it didn't skip a beat. The unrelenting pounding cracked the chainguard, so I broke it off before it could jam into any moving parts. I checked the oil repeatedly, but it never needed topping up. I never cleaned the air filter.

Toward the end, the b~ce felt like it needed a good servIce and a shock rebuild, but other than that, a good wash and a few consumables would've made It ready to pose at the local biker hangout again.

In all, pretty impressive stufifrom the reborn italian bike-maker. When can you get your own TnT? Former Bimota importer Moto Point (724/593-6208; www.motopoint.com) is selling DOT-legal Tornado superbikes now, and hopes by the end of the year to have the TnT in stock, price to be determined. If you get one, take some advice: Stay on asphalt! Gary Iriman

grip the bars lightly. Still, I sit down and hold on with white-knuckle ferocity.

I have little faith in myself and close to none in the tires. This is a true ride into the unknown. All I do is stare at the car’s wheel-tracks and try to follow. It’s painfully slow going.

At times it’s just painful.

The sand changes from fairly hard-packed stuff peppered with pea-size gravel to the fine, golden, almost-dustlike granules that form dunes. It changes from one kind to the other for the next 150 or so miles. Within a few minutes, I was confident on the gravely stuff. I learn to judge the softness of the sand by looking at the tracks left by the car.

I stay within 50 yards of my four-wheeled guide, still gripped by paranoia about being left behind. Soon, too soon, the gravely sand ends. I’ll later realize that when the small tufts of camel grass appear, the going gets soft. For now,

I just paddle, slow down, get stuck, fall over. I know momentum is everything, but every kick of the bars forces me to back off the throttle, losing any semblance of balance and falling.

I haven’t been out of first gear, except for a short aborted experiment, since leaving the piste 15, 20, God knows how many miles ago. The 5-gallon gas can strapped to the passenger seat has been rabbit-punching me in the lower back all day. Even through my back protector, the constant poking is beginning to really aggravate me, but I’m determined to stay as self-sufficient as possible, even though I could put it, and my backpack, in the Jeep with the Dutch guys.

Finally, I learn to keep the rear wheel spinning: Clutch out in first gear, revs between 2500 and 3500. Soon, riding becomes rewarding. Sometimes I’m bounced so hard out of the saddle,

I back off and grind, literally, to a halt. When this happens the bike’s either on its side or so submerged in soft sand I can step off it and leave it parked bolt upright. Getting unstuck is not fun. 4

every crash it takes time for my confidence to build,

. to get back in the rhythm, but it always comes back. I need plenty of small rests and drinks of bottled water. This is the cool time of year, but it’s still in the mid-90s between 11 and 4. I’m told the guide doesn’t take a drink all day. After four hours we made a proper stop. I take off my helmet and jacket as Mr. Abba borrows a camping stove to make a pot of mint tea.

“You look like an accident happening on a two-hour delay,” I’m told, but still feel remarkably upbeat. One shin is grazed, but I’m not badly hurt. Mr. Abba points to a mountain in the distance and says we’re staying beyond that. It’s impossible for me to judge how far away it is. But the day no longer felt like it would last forever.

We drink the mint tea out of shared shot glasses. It’s so sweet it makes my eyeballs sweat. I’ve seen tire tracks today, a few camels and even a couple of camel herders standing motionless, miles from anything. As we let the vehicles cool, a goat herder we passed a couple of miles ago appears. Ronald gives him a slice of cake and a carton of juice. Mr. Abba knows him. Mr. Abba, we discover, knows virtually everyone in the desert or on the road, and says the goat herder is a bit crazy. I’d be more surprised if he wasn’t. I’d be dead in 24 hours if left to fend for myself out here. I think the hopelessness of the situation would get to me before I actually died of thirst.

During the following hours I develop a new style of sand riding: I put my hands out as if I’m signaling a marauding pig to halt, and gently hold the back of the bars with the palms of my hands. It works. This and learning to pick better lines rather than fixating on the next 10 feet mean by the end of the day I’m on a high. The TnT shimmies constantly below me but it feels comfortable, natural now.

Past the mountain we roll up to a Bedouin camp made up of a large, square fabric tent and a couple of smaller ones. Goats and camels meander about. As do Mr. Abba’s relatives, numbering about half-a-dozen, the entire population of camp.

It wasn’t made clear in Nouadhibou, but I learn I’m sleeping in the communal tent. With the sun setting, Mr. Abba WR

asks if I have a knife. I show him my expensive Victorinox multi-tool. He feels the blade and gives it back, with an expression I take to mean,

“Why bother bringing a knife into the desert that would struggle to

slice a banana?” He pulls his own out. It’s a big, dirty old French thing with the tip broken off.

Five minutes later I see him using it to hack a goat’s head half off. The goat lies dead but still kicking in a pool of its own blood in the sand. Right next to my home for the night. An hour later, I’m being passed bits of the goat’s cooked liver. It tastes like lamb. I’m glad I like it, because there is nothing else to eat except boiled rice soaked in the goat’s, uh, liquids. A new experience. As is drinking camel’s milk out of a communal bowl the size of a wash basin.

next morning I crash in the first 5 miles of an 80-mile day sand. A wave of frustration and despair nearly drowns te. The accident smashes one of the accessory fans Benelli specially fitted to the side-mounted radiators for this trip.

The rear brake lever also is bent. It still works. But only until I try to straighten the lever by kicking it a few times, which snaps the delicate plunger in the master cylinder.

There is no choice but to get back in the saddle and keep riding. My reward is being taught a lesson in life: No matter how little talent or aptitude you show, perseverance can paper over a lot of cracks. By 3 in the afternoon I’m blasting across a hard piece of the desert floor at 70 mph in fourth gear with the rear wheel spinning, and riding the soft stuif with the loose-limbed cool of Steve McQueen. I consider taking up smoking to add to the look. By 4 o’clock, I’m thinking I could

survive racing the Dakar Rally.

That night, my last in the desert, is spent in another Bedouin tent-this time shared only with the Dutch guys-on the beach with the Atlantic crashing a few feet away. Except for home, it’s the best destination I’ve ever reached on a bike. I’m so happy it’s hard to describe. I’m no longer scared of dying in the desert or of crashing and breaking my ankle or collarbone. No longer worried about the possibility of getting lost and being left behind. And because the engine and electrics haven’t missed a beat, I’m not scared of breaking down. I’ve ridden a Benelli TnT fitted with street tires through a section of the Sahara Desert. I know that’s a first.

n two days, the bike’s sandblasted shock will be battered into submission by the most hideous 150-mile section of road I’m ever likely to ride. The noise of its seal popping at 80 mph will be as loud as a gunshot. In two days I’ll have seen piles of dead hammerhead sharks, and met immaculately prepared Italians on overland KTM Adventures who’ll barely believe what the TnT has done. In two days I’ll have been awakened and soaked to the skin by a thunderstorm in a place where it rains only a few days a year. I’ll have ridden 60 miles down that bike-torturing, cow-infested mud trail and I’ll have survived Rosso, that parasitic scumpit of a border town.

And in two days I’ll be stuck at that Senegalese border with almost no money left, on a beaten-down bike, dog-tired, filthy, damp with nervous sweat and being threatened with strip searches, yet still knowing Dakar and the end of the journey is just a day or so away.

If I knew all that, maybe I’d have just stayed at the beach staring at the Atlantic a little longer before heading back north to Morocco and Europe. Or maybe I never would have left Spain in the first place. In hindsight, I’m glad I couldn’t see any of it coming. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue