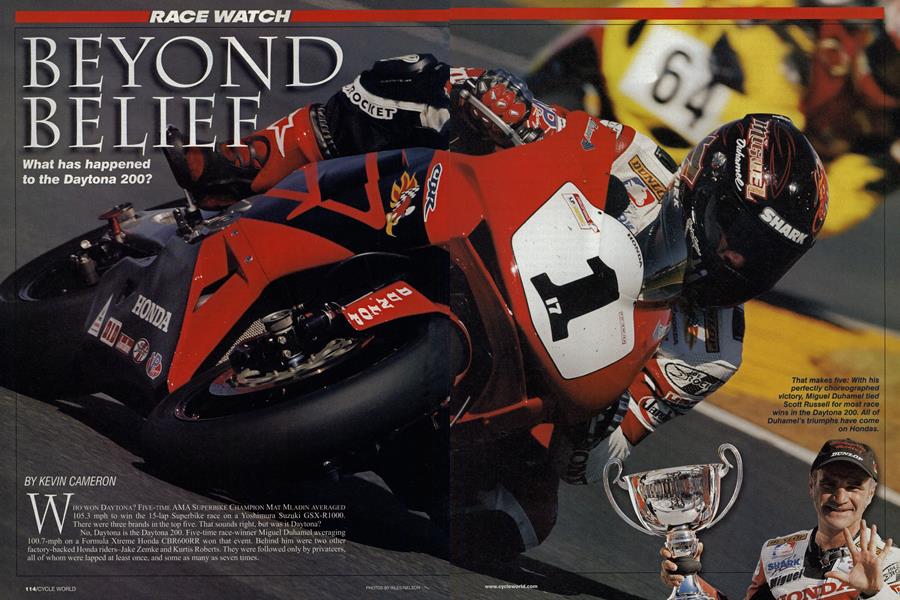

BEYOND BELIEF

RACE WATCH

What has happened to the Daytona 200?

KEVIN CAMERON

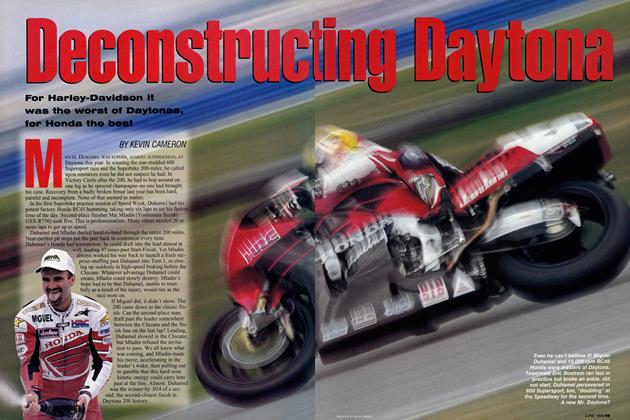

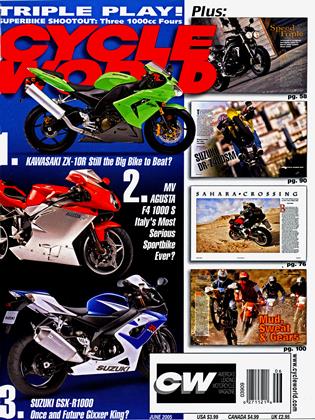

WHO WON DAYTONA? FIVE-TIME AMA SUPERBIKE CHAMPION MAT MLADIN AVERAGED 105.3 mph to win the 15-lap Superbike race on a Yoshimura Suzuki GSX-R1000. There were three brands in the top five. That sounds right, but was it Daytona? No. Daytona is the Daytona 200. Five-time race-winner Miguel Duhamel averaging 100.7-mph on a Formula Xtreme honda CBR600RR won that event. Behind him were two other factory-backed Honda riders—Jake Zemke and Kurtis Roberts. They were followed only by privateers. all of whom were lapped at least once, and sonic as many as seven times.

There’s more. Soon you’ll read advertisements proclaiming, “Kawasaki wins Daytona.” Which it did-defending champion Tommy Hayden topped the intensely competitive Supersport race. And for good measure, Vincent Haskovec won Daytona, too-on an M4/Emgo Suzuki GSX-R1000 shod with Pirelli tires. That aspect of Daytona was the Superstock race, in which top speeds of more than 195 mph were seen, and which Yamaha was confidently expected to win.

Is this what Daytona has come to? Each manufacturer has its own event? Everyone wins in a competition-free environment?

Wait, wait! I can explain! Everything here has a kind of logic. The Daytona 200 couldn’t continue in its previous lOOOcc Superbike format because the Speedway knows that the deaths of heroes are bad for everyone-and for business. The warning was given last year, when there were high-speed tire failures during testing in both Superbike and Superstock. Therefore, the classic 200miler could not be for tire-eating, 195mph lOOOcc bikes-Superbike or Superstock. Not even on the new, revised racetrack that uses only the east banking and therefore heats tires less. The only possible AMA responses to a Daytona ban on Open-classers were: 1) move the

race elsewhere or 2) run one of the existing 600cc classes.

The AMA chose the second option, the “spare” 600cc FX class, which was created last year and drew the attention of only Honda and a smattering of privateers. That became the Daytona 200. See the logic? The illogic, many pointed out, lay in describing middleweights as “Xtreme,” when in years past FX was an unlimited class.

In the weeks leading up to the race, I made these explanations to countless people, and they have looked at me as if I’d lost my mind. The common reaction? “600 FX? That’s not the Daytona 200!”

Mladin, speaking in the Speedway pressroom, pointedly used the word “pathetic” to describe FX. Lap times, he noted, were 4-5 seconds slower than in Superbike.

No doubt this confusion will resolve itself in time. Public life teaches that if certain statements are often enough repeated, they are believed and therefore become in some sense true. Time heals all things. Pick your favorite truth.

In the meantime, let’s talk about the Superbike race. Mladin set the qualifying lap record for the new 2.95-mile course at 1:38.2, with Yoshimura Suzuki teammate (and class rookie) Ben Spies second on the grid at 1:38.9 and former World Superbike champ and ex-MotoGP rider Neil Hodgson on the factory Ducati Austin 999R third at 1:39.8.

Where were the Hondas? Implementing a decision made three years ago, American

Honda has taken over U.S. racing development from HRC. Naturally, it takes time to match the factory’s R&D pace, so top Honda qualifier Duhamel was down in sixth with a time of 1:40.8. This is quite a

comedown for Honda, but it has the resources to make its way back to the front.

Is the newly altered course safer for lOOOcc bikes? Spies said he’d found that three laps at qualifying pace would destroy the tire, so racing even 15 laps instead of the traditional 57 would be a carefully judged process of keeping no farther ahead of second place than the tire would tolerate. In Superbike, that’s just what the stopwatch revealed. Mladin ran hard right from the flag to lead all but one lap, yet Hodgson in second (who needed five laps to overcome Aaron Yates) was able for a time to close the gap. The reason for this that Mladin’s tire faded first. Both men gave controlled performances of advanced tire management.

Why is the banking hard on tires? Tread rubber must bend to enter the tire’s flat footprint, and must unbend to leave it. Bending rubber generates heat because rubber is not perfectly elastic. The heavier the load the tire carries, the bigger its footprint becomes, and the more its tread rubber must bend to enter and leave that footprint. This is why the most hazardous condition for aircraft tires is not the impact of landing, when the airplane is least heavy, but rather taxiing and takeoff at maximum gross weight, when each main bogie tire is carrying close to 50,000 pounds. So it is at Daytona, where

centrifugal force from running on the banking generates larger-than-normal tire loadings and thus larger-than-normal heating. Centrifugal loading increases with the square of the machine’s speed, so a jump from 180 mph with a 750cc Superbike to 195 mph with a lOOOcc Superbike would increase tire loading by 17 percent. The tires heat up on the banking and then cool off in the infield. Less banking with just as much infield equals cooler-running tires.

The problem is that riders need at least some grip in the infield, so the tires cannot be designed for the single hot operating point of running on the banking as are NASCAR tires. The result is tires that must be made a bit too soft to be completely comfortable on the banking, yet too hard to give real racing grip in the infield.

The practical solution over the past several years has been to build Daytona tires with two or three different tread rubber compounds: 1) a hard one offset to the left of tread center for hot, high-speed running on the banking; 2) a much softer, hotter-running compound to generate infield grip on the cooler right side of the tire and; 3) perhaps a medium compound for full-lean infield running on the left side of the tire. Getting all these different rubber compounds to cure together on the same tire, making sure they stay put and achieving good directional stability as the machine heels have not been easy to solve. Nevertheless, Mladin and others had high praise for the consistency and performance of this year’s Dunlops.

How do tires fail? Sudden vibration on the banking signals blistering of the treadvolatile elements in the rubber compound expand as gas when overheated, raising

bubble-like blisters. A more extreme form of failure is chunking-bullet-like detachment of strips of tread rubber as a result of breakdown of the adhesive bond between tread and carcass. Tire-makers employ rig tests that they have found to model Day-

tona conditions, pressing spinning tires forcibly against high-speed rotating drums.

Mladin and crew chief Peter spoke highly as well of the new GSX-R1000, which makes more power than last year’s model and has an upgraded chassis. Per AMA rules, ur-cylinder Superbikes are limited to stock valve lift and material, but what is stock can be upgraded at the yearly model change.

The top-five finishing order in Superbike was Mladin, Hodgson, Spies, Yates and Jake Zemke. Hodgson impressed everyone with his ability to adapt to the Speedway and produce a top performance first time out. Of his ride, he said, “Every time I pushed, I was tucking the front.” Zemke and sixth-place-finisher Duhamel, only 7 and 8 seconds back, show that Honda remains vitally interested in Superbike.

S emi-works teams offer an opportunity for factories to test the water. Will this cam/crank/piston go 200 miles? Let’s see: Josh Hayes made one lap on his Attack Kawasaki and was out with a smoking engine. Yet as his eighth-place qualifying run showed, the bike had speed. A “disinformation officer” told me the failure was “an oil-level problem.” Meanwhile, the equally second-level Jordan Suzuki team put Jason Pridmore seventh-a fine start for this new group, which is spending its money and efforts wisely. It’s grand to see how a good ride can perk up a rider who was previously considering retirement.

Superstock continues to amaze and to pose the question, “If Superstock bikes are this fast, why do Superbikes exist?” Yates topped qualifying at the last moment with a 1:39.6, equivalent to third on the Superbike grid, and race-winner Haskovec averaged 103.9 mph for the 13 laps. I later spoke with Haskovec’s engineer Keith Perry, who said, “We’ve been here almost two weeks now and we

tested setups that are a lot faster than what we ran in the race. But the tire would only go five laps with them.” This emphasizes the difference between a onelap setup (qualifying only) and a true race setup. It’s romantic to dream of “goin’ for it,” but real-world racing requires the ability to postpone gratification.

Haskovec, who ran sixth in early going behind Pridmore, Yates and Yamaha’s Jamie Hacking and Jason DiSalvo, later said he’d “enjoyed watching ’em wobble.”

As he came to terms with his machine, he moved up, aided by DiSalvo and Hacking overshooting comers. At the end, it was Haskovec by .3 of a second over Yates and Pridmore.

And now for the really big news in Superstock: Haskovec won on Pirelli tires, completely blowing away the popular idea that the Italian company’s position as “spec” tire maker for World Superbike robs it of any motivation to do development. Making a successful Daytona tire is a remarkable accomplishment for anyone, let alone an “outsider.” Daytona track changes had their greatest impact in Supersport, in which Tommy Hayden was able to do the previously impossible and “clear off’ to win by nearly 4 seconds over the Yamahas of Hacking and DiSalvo. In previous years, with the track including both east and west bankings, no one had the power to break the draft of a pack of machines. The elimination of the west banking this year has reduced the power of drafting, which used to bunch as many as eight bikes together. Although fans stalwartly cheered themselves hoarse, hailing this artificial situation as “close racing,” it clearly had the makings of a giant lastlap pile-up as riders jostled for advantage in the high-speed run from chicane to flag. It was in such traffic that Duhamel so often displayed incredible ability to find “good air” that would carry him yet another win. Alas, the number of classes and rules limiting factory riders to only two of them robbed us of his sooften-decisive presence in Supersport.

In an honest ordering of these four classes, Formula Xtreme must come last. American Honda is surely embarrassed that its three U.S.-developed bikes ridden by Duhamel, Roberts and Zemke lapped even the fourth-place finisher, Suzukimounted privateer Danny Eslick. This is exactly the kind of show that Daytona supremo Bill France Jr. once deplored as “a stinker.”

No special quick-change apparatus was

permitted in this race but full fuel and two tire changes were achieved in as little as 13 seconds. Duhamel’s stops were flawless, and he won by 42 seconds. Roberts, running second, had bad luck in the pits, which cost him the race.

Everyone at Daytona wanted to know the future of FX. Is it the new “600cc Superbike”-a class that will replace 1000s? Is it a placeholder for the 1000s at a track the latter have outgrown? Is it a temporary expedient that will disappear

in a year or two as tire development makes present concerns less cogent?

Other factory teams made it clear they want to race “all together” in a single class (presumably Superbike), but were unwilling to gamble on hasty development of 200-mile FX machines. Decisions in racing are made by executives normally confined to the hospitality suites, where racing is just one chip among many in the great game of advertising. They are innocent of the realities of engine reliability. The production crank is lowalloy steel, while a race crank may have to be made of special vacuum-remelted material that requires long-lead-time ordering. Pistons that are reliable at stock redline may develop wristpin-boss cracks at race rpm, threatening an engine wreck. This triggers a money-eating cycle of research, re-design and testing. What if the anti-friction coating flakes off one or two sophisticated titanium valve tappets at the last test before the season starts? Ignore it and hope for the best? Lose 500 rpm by reverting to the stock steel tappets? Jump down the supplier’s throat? Reliability takes time and money to achieve. Without it, entering a 200-mile race is just gallant foolishness and potential negative advertising. Testing is the racing fourstroke engine’s middle name.

Yamaha and Kawasaki call for rules stability and want to return to full participation. They want rules to remain in place long enough to justify the effort of building and proving equipment to suit. Critics point out that these compa-

nies already operate Superbikes in other venues. Why not in the U.S.? Yet there is clearly concern that the AMA may abruptly announce further changes that will make nonsense of forward planning. Production classes such as Supersport and Superstock will be well subscribed because reliability testing for them is a part of the normal product-development cycle, not a separate expense billed to the racing department.

I feel for the AMA, encircled as they are by large forces beyond their control. The manufacturers lobby to race the bikes they most want to sell-the 1000s-but the Speedway sees 1000s as potential trouble of the Dale Earnhardt kind, using its traditionally strong influence with the AMA to promote smaller-displacement alternatives. Do spectators care? Don’t all faired bikes look and sound the same from the stands? U.S. roadracing is viewed as shaky by some, lacking a big sponsor, with some events threatening to drop off the schedule. Does this call for hunker-down conservatism or for bold, new gambles? Should the AMA seek common ground with WSB? This, allowing manufacturers to develop one bike rather than one for each rulebook, is touted as encouraging all to participate. Yet Daytona has in the past set its face against Euro-centric rules, preferring to craft its own kind of red, white; and blue racing.

No sane person claims to know what will happen next. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue