Doctor for a Day

I WILL BECOME A MILlionaire this year, according to my latest Social Security statement. That's not to say I will make a million dollars this year, nor that I possess a million dollars, just that I’ve earned a million dollars in this lifetime.

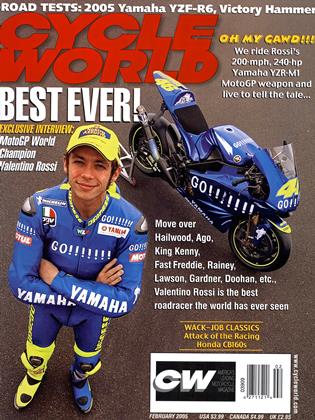

Valentino Rossi will make $8.5 million this year. half of his reported $17 million two-year deal to race the Gauloises Yamaha YZR-M1 in the MotoGP World Championship. And that's just from his primary sponsors; add to that his income from various promotional deals, both motorcycle-related and mainstream, and that figure will likely double. If he were to win the Ay world title again in 2005, as he did in 2001, 2002, 2003 and 2004, his annual income could conceivably make him one of the richest athletes in the world. Not unlike Michael Jordan, who reportedly attended the season-ending Gran Premio Marlboro de la Communitat Valencia. Not that l ever saw him there...

Big money is everywhere you look in the MotoGP paddock, and you can’t help feeling insignificant in its presence. The only thought that kept me from feeling like an unwashed punter was the fact that on the Tuesday following Sunday's race, 1 would get to ride Rossi’s Yamaha. No one this side of “The Doctor’’ himself would fail to be impressed by that.

Being invited to ride the world champion’s motorcycle is the once-in-a-1 ifetime feather in a motojoumalist’s cap, and I’ve stuck around long enough to have it happen twice. My first opportunity came in 1994, when 1 flew to Japan to test the Honda NSR500 on which Australian Mick Doohan had just won the first of his five world titles. Never mind that I had to learn the daunting 3.6-mile Suzuka circuit on a fire-breathing, 190horsepower twostroke. Did I mention it was damp? Fortunately, the bigbang Honda was the most docile and user-friendly of the 500s, which is in no way meant to imply that it actually was docile or user friendly, just that it was more so than its competition.

Seven minutes, anyway...

BRIAN CATTERSON

The same can be said of Rossi’s Yamaha. In the days leading up to the test, I kept telling myself that the Ml was “just a motorcycle.” And as one tester after another reported that it wasn’t in fact that difficult to ride, I actually felt kind of relaxed-in marked contrast to Steve Westlake of England’s Bike magazine, who looked like he was about to have kittens!

The only “Valentino Moment” I had occurred while I was awaiting my tum in the garage. Having donned my Rossi Replica AGV helmet and Dainese leathers, I was suddenly overcome by the realization that I was sitting in his chair, watching his crew prep his motorcycle...for me. Gulp.

As the mechanics fiddled with the electric rollers that start the engine, crew chief Jeremy Burgess cracked a wry grin at the sight of a 6-foot, 200-pound “Rossi Replica.” Fortunately, the sound of the Yamaha’s engine exploding to life drowned out whatever he said.

With the many photographers on hand snapping photos, I adjusted the front brake lever to fit my size-XL paw, then pulled in the clutch lever, gave it a little gas and eased down pit road. Thankfully, given the dozens of onlookers, I didn’t stall it like a number of my peers had done.

The M1 is equipped with a pit-road speed governor, the engine making weird popping noises and “snapping at the reins” in first gear. With no pit-road speed limit enforced during our test, I upshifted to second and, even at only partthrottle, the front end came right up! This was going to be memorable...

Having never ridden at Valencia before, I had no delusions of impressing Rossi’s crew with my lap times. To the contrary, the only way I could possibly make an impression was by binning it, and I was not going to do that! At the morning riders’ briefing, Yamaha PR chief Martin Port-himself a former motojoumalist, having done a four-year stint at Australian Motorcycle News-warned us that there were just two Mis. If one got wadded, we’d have to share the other, which would mean fewer laps for everyone. Considering that we were only getting four laps as it was, that wouldn’t have gone over well.

Though Rossi appears elfin in photos and on TV, he’s actually nearly 6 feet tall, so I fit on his bike just fine. It didn’t feel that different from an Rl, actually, with a narrow gas tank that encourages getting your weight over the front end. The main difference is the weight, or lack of it: At 319 pounds, the Ml is fully 100pounds lighter than an Rl, its engine alone weighing 30 pounds less.

No surprise, then, that it’s quite easy handling and maneuverable, which Rossi claims is his primary advantage over the Honda hordes. Arriving at the Turn 2 hairpin for the first time, I tipped it in and my knee promptly kissed the tarmac. The Michelin slicks naturally encourage quick transitions to full lean, but the Ml doesn’t “fall in” like the NSR500 did a decade earlier, its steering remaining neutral even while trail-braking into comers.

Not that I was comfortable doing that. The carbon brakes with radial-mount four-piston Brembo calipers provide an immense amount of stopping power, and aren’t easy to modulate. A light pull with one finger will slow the bike, and a healthier tug will make you intimate with the gas tank! On the numerous occasions I sensed I was entering a corner too fast, I opted to continue braking straight up and down rather than attempt to balance braking and cornering forces, it would take some time to develop the necessary deft touch, and perhaps this explains why Rossi uses four fingers.

Well, that and the fact that he doesn’t have to blip the throttle on downshifts. Like all the other MotoGP bikes, the Ml is equipped with two features aimed at eliminating wheel-hop under heavy braking: a slipper clutch and an electronic engine-braking (or more accurately, ¿m/f-enginebraking) system. Called ICS for Idle Control System, the latter works by opening two of the four throttle bodies a small amount, effectively turning up the idle. Or as Kevin Cameron surmised, it lets the engine produce just enough power to counter its frictional losses.

A word about that: Whereas Honda utilizes a V-Five, and Ducati and Suzuki V-Fours, Yamaha has retained a traditional inline-Four. The reasons are twofold: First, with just one cylinder head, it has half as many camshafts as the Vmotors, which means less friction. Second, it’s more compact, which allows it to be positioned closer to the front wheel. This forward weight bias pays dividends in both handling and in countering wheelies, which the 240-horsepower machine is eager to do.

Ordinarily when you ride a fast bike at a roadrace track, there’s a comer that makes your butt pucker. And while Valencia does have a crested, fourth-gear sweeper that the racers take at 125 mph, recent developments in engine firing orders, traction-control systems and tire construction mean the wheels now stay more or less in line.

Between the 2003 and 2004 seasons, Yamaha built four different engines for the Ml, with even and uneven firing orders, four and five valves. Rossi tested all of them and chose the four-valve big-bang motor, confirming the beliefs of Yamaha tech chief Masao Furasawa.

At the same time, the M1 adopted a Magnetti-Marelli engine-management system, one feature of which is a traction-control system that compares the speeds of the front and rear wheels. Should the rear “spin up,” the computer reduces power output accordingly. This same system can be used to combat wheelies. Not that I sensed any of this from the saddle; it all felt fairly normal, which is the highest possible praise.

Where the Ml really spooked me was on the start/finish straight. According to the 2D data-recording, Rossi takes the final left-hand corner in second gear at just over 50 mph, yet a half-mile later he’s doing 194 mph! So when I tell you it accelerates as hard as a dragbike, believe me.

Thing is, the Ml has a shorter wheelbase, a higher center of gravity and no wheelie bar, so it’s a much wilder ride. I found myself hanging on for dear life while making the full-throttle upshifts allowed by the electronic quick-shifter, the bike wheelying through second, third and even fourth gears! Forget about looking down at the LCD tach, it was all I could do to see the shift light illuminating at 14,200 rpm, so fixated was I on my faraway braking point. Which was a friggin’ billboard, thank you very much-I couldn’t possibly spot a little white brake marker at that speed.

To say the four laps went by in a blur would be nothing if not accurate. My only vivid memory was catching and passing Australian Motorcycle News Editor Ken Wootton on the other Ml, which was worth bragging rights at the hotel bar that evening if little else. But it probably looked like snail racing from the pit wall.

Handing the bike back to the mechanics in the pits, they patronized me by asking what I thought. “I could do an endurance race on this thing,” I told them. “In fact, I’d like to...”

I may only have gotten seven minutes on Rossi’s Ml, but that’s seven more than I deserved. Thanks, Yamaha. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

February 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Fine Art of Planning To Crash

February 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaking It Easy

February 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupMoto Morini Lives!

February 2005 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupAmerica's Fertile Sportbike Ground

February 2005 By Mark Hoyer