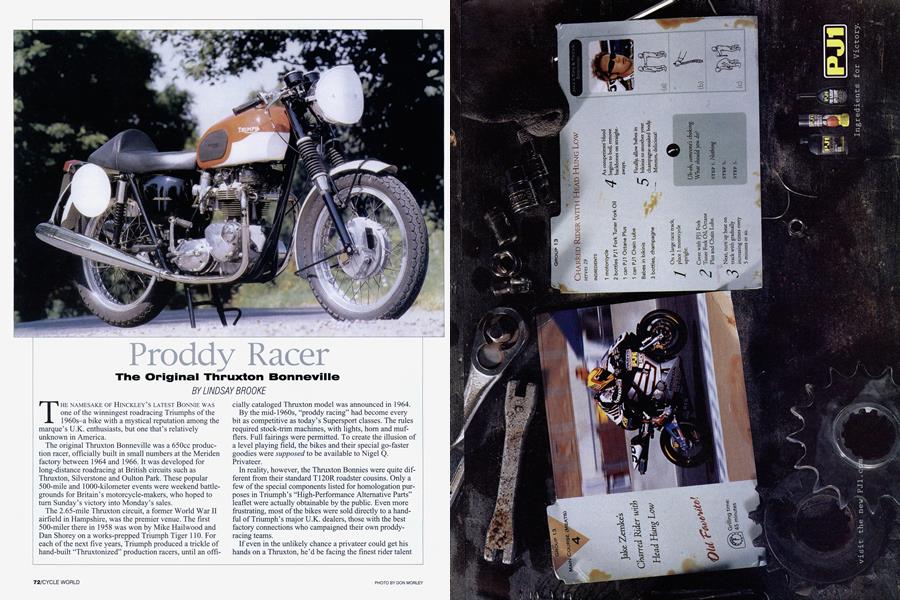

Proddy Racer

The Original Thruxton Bonneville

LINDSAY BROOKE

THE NAMESAKE OF HINCKLEY’S LATEST BONNIE WAS one of the winningest roadracing Triumphs of the 1960s-a bike with a mystical reputation among the marque’s U.K. enthusiasts, but one that’s relatively unknown in America.

The original Thruxton Bonneville was a 650cc production racer, officially built in small numbers at the Meriden factory between 1964 and 1966. It was developed for long-distance roadracing at British circuits such as Thruxton, Silverstone and Oulton Park. These popular 500-mile and 1000-kilometer events were weekend battlegrounds for Britain’s motorcycle-makers, who hoped to turn Sunday’s victory into Monday’s sales.

The 2.65-mile Thruxton circuit, a former World War II airfield in Hampshire, was the premier venue. The first 500-miler there in 1958 was won by Mike Hailwood and Dan Shorey on a works-prepped Triumph Tiger 110. For each of the next five years, Triumph produced a trickle of hand-built “Thruxtonized” production racers, until an officially cataloged Thruxton model was announced in 1964.

By the mid-1960s, “proddy racing” had become every bit as competitive as today’s Supersport classes. The rules required stock-trim machines, with lights, horn and mufflers. Full fairings were permitted. To create the illusion of a level playing field, the bikes and their special go-faster goodies were supposed to be available to Nigel Q. Privateer.

In reality, however, the Thruxton Bonnies were quite different from their standard T120R roadster cousins. Only a few of the special components listed for homologation purposes in Triumph’s “High-Performance Alternative Parts” leaflet were actually obtainable by the public. Even more frustrating, most of the bikes were sold directly to a handful of Triumph’s major U.K. dealers, those with the best factory connections who campaigned their own proddyracing teams.

If even in the unlikely chance a privateer could get his hands on a Thruxton, he’d be facing the finest rider talent the big dealers could buy. The star-studded list of pilots who put Thruxtons into winner’s circles included Grand Prix aces Phil Read, Rod Gould and John Hartle;

Triumph works rider Percy Tait; endurance-racing veteran Dave Degens; and future Isle of Man TT hero Malcolm Uphill.

But the bikes themselves were competitive right out of the box. Doug Hele made sure of that.

Triumph’s development chief had left Norton in late 1962 after making the Featherbed-framed 650SS the machine to beat in proddy events. One of Hele’s first priorities at Triumph was to improve the new unit-construction 650 Twin’s overall performance. By launching the Thruxton Bonneville program, Hele and his small team of engineers intended to transfer the lessons learned in production racing to improving Triumph’s standard models.

Within a year of Hele’s arrival, the first batch of 19 Thruxton racers was completed. Those 1964 machines were subtly modified T120Rs-blueprinted engines, dropped handlebars, bum-stop racing seats, rearset pegs and freer-flowing police-spec mufflers. An Avonaire full fairing was optional.

“We took one of our earliest machines to Thruxton in ’64, where Percy and Fred Swift rode it to second place, less than a second behind the winning Norton,’’ Hele recalled years later. “I realized then that with more development work on the engines, our 650s could be winners.”

Those changes came as part of the largest Thruxton build^!9 machines assembled in consecutive numbers during May, 1965. They featured significant improvements in power and handling. Engine performance was boosted by cleverly combining Triumph’s mild Thunderbird camshaft with new 3-inch radius tappets, which increased valve lift and duration. The cam was given a pressurized oil feed to improve durability.

The cams and Amal Monobloc racing carburetors complemented a unique Thruxton exhaust system. Its header pipes were 1 i/2-inch diameter as they exited the ports, then necked down to 11/4 inch to speed gas flow-a trick Hele’s team learned from U.S. dirt-track tuners. The headers were connected by balance tubes to further aid gas extraction and boost midrange torque. Sensuously long silencers, radically upswept for cornering clearance, were basically megaphones in disguise.

Like most of the speed parts, the entire Thruxton exhaust system was unobtainium. Privateers wanting to build a proddy racer were out of luck. Even the favored Triumph dealers couldn’t buy the critical stuff.

Engine output at the crankshaft, according to a 1966 factory dyno report, was 54 bhp at 6500 rpm-5 horses up on a stock T120R.

The power could be delivered through an optional close-ratio gearbox. To put Triumph steering and roadholding on par with the Nortons, Hele steepened the ’65 Thruxton’s steeringhead angle, forks received shuttle-valve damping and 18inch Dunlop aluminum rims replaced the steel stockers. Many of these racer-inspired changes were incorporated into the late-Sixties T120R and TR6 streetbikes.

A batch of just seven Thruxtons left Meriden in 1966. For the next three years, the model was further evolved with more streamlined bodywork, a new 8-inch twin-leading-shoe front brake, GP carburetors and a 5-gallon aluminum fuel tank. But most of the 16 bikes built from 1967 were exclusively works machines for Tait, Hartle and a few others. The final units produced nearly 60 bhp-good for 140 mph on the Isle of Man.

The well-connected dealers who bought Thruxtons paid about £45 ($200) more than the price of a standard T120R Bonnie. What a bargain! The Triumphs broke Norton’s grip on British proddy racing, winning the major 500-mile events in 1965, 1966 and 1967 and scoring the famous 12-3 hat-trick at Thruxton in 1969.

The full-works racers fared equally well, with Hartle winning the inaugural 1967 Isle of Man Production TT and Uphill reprising the victory in 1969. He averaged 99.99 mph for the race, with one lap exceeding 100 mph-the first time a production-based TT bike had lapped at “the ton.”

But 1969 was the Thruxton Bonnie’s last hurrah. By then, Doug Hele’s team was developing racing versions of the new three-cylinder Trident.

Over 30 documented Thruxton Bonnevilles survive today, says Hugh Dickson, who owns a 1964 example. His Thruxton Registry in the U.K. (011-44-1202-888-136) maintains a listing of existing machines, and he has the factory dispatch roster of Thruxton engine/frame numbers. It’s a useful place to start if you’re lucky enough to find one of these most rare, beautiful and mighty quick Bonnies. □

Lindsay Brooke is author of three books on Triumph ’s history, Triumph in America, Triumph Racing Motorcycles in America and his newest, Triumph Motorcycles: A Century of Passion and Power.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSecret Daytona

JUNE 2004 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat To Do In Winter

JUNE 2004 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCA Short History of Chassis Flex

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

JUNE 2004 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Max!!!

JUNE 2004 2004 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupFormula Bmw: K-Bike Power For F-1 Hopefuls

JUNE 2004 2004 By Kim Wolfkill