MOTEGI PIT WALL

Sights and sounds of MotoGP

KEVIN CAMERON

RACE WATCH

WITH TOKYO A MERE 13 hours ahead, I was winging my way to the Pacific Grand Prix at Motegi, Japan.

Soon I would hear the 990cc four-strokes of MotoGP in person for the first time.

At Narita Airport I first joined a group of journalists headed for Yamaha’s plants and museum in Hamamatsu, four hours south. Ten days earlier, Yamaha PR maven Brad Banister

had invited me to “Thirty Years of the Yamaha YZR500,” an exhibit commemorating three decades of two-stroke racing. Then he added, “And if you like, you could stay for the GP on the weekend.”

I like!

So, with the Yamaha museum, the 45-floor hotel, sacred Mt. Fuji and Japan’s many used car lots behind me, I stood on the inside of Turn 1 at Twin Ring Motegi looking forward to witnessing MotoGP first-hand.

Valentino Rossi’s five-cylinder Honda RC211V doesn’t accept throttle when its engine is cold, so he held the clutch in, coasting, and revved the engine as high as its cold intake tracts would allow. Then, a gear high, he chugged away. Three laps later, the sounds began to make sense.

Any interested person would quickly be able to recognize the bikes with eyes closed. The engines of the Hondas, Ducatis and the KR Protons all run without a hint of four-stroke closed-throttle popping flow being so diluted with exhaust from the previous cycles that each cylinder fires only when it has accumulated enough charge to ignite. This is a wonderful rush of sound, and when the rider throttles up and accelerates out of the turn there is the classic four-cylinder ripping shriek.

The most melodious is the Proton VFive. Although this is the first of three planned engine designs, “useful,” says team manager Kenny Roberts, “only as a boat anchor,” everything I saw appeared to be first-class. Nice thin castings; black Formula One-style carbon cam and crankcase covers; lots of the obligatory CNC-milled parts. While the 75.5-degree Honda V-Five has a harsh, unmusical note, the Proton’s resonant and banging on deceleration. This, I would learn, comes from the use of “throttle-kickers”-devices that open the throttle slightly to admit air, and of course fuel, to the intake system, making just enough power to cancel engine braking. Two-stroke riding techniques are hard to unlearn, apparently. Honda uses solenoid-operated air valves-one per intake pipe-to smooth closed-throttle running.

Here comes a Kawasaki, decelerating, its transverse fourcylinder engine backfiring rapidly, making a sound like a stack of boxes tumbling down a stairway. No throttle-kicker here-this cacophonous banging comes from the idle intake sound suggests an even firing order.

“Not quite,” Kenny says. “When the Honda engineers came into our pits, they said, ‘Oh, 60 degrees. Why did you do that? Now you need a balance shaft.’ But I told them we made it narrow because we knew we were going to have to move it around in the chassis before we got it right.”

The bike, he says, has just now become reliable enough to run hard, but still lacks detail refinement like concerted tuning of airbox, intake length and pipe dimensions. Therefore, Proton is a public R&D program. By the time you read this, the Mk. II version will be well into testing.

I think the harshness in the Honda’s sound comes from firing pairs of cylinders fairly close together-a sound I remember from the 1965 Superhawk. A bigger, deeper, more lyrical tune comes from the Aprilia Triple, whose firing order is most certainly even. Paddock gossip puts this bike downfield because its engine is tall and heavy. A more compact engine is in the works. But slow progress is also a symptom of not enough cash burning in the R&D furnace.

All but one of the Yamahas-that of Alex Barros-make the boxes-fallingdownstairs noise when decelerating. When I asked Yamaha’s GP engineer, Mr. Yoda, what is different, he looked uncomfortable. Not permitted to say? He smiled and nodded. Perhaps there’s a throttle-kicker on Alex’s bike?

Why not just use Superbike-style back-torque-limiting clutches employing ramps? Under power, the connection is solid, but when the rear wheel drives the engine, the reverse torque twists the ramps apart, easing clutch-spring pressure. While this stops rear-wheel hop during braking, it lacks versatility because a different back-torque adjustment would be needed for each of the six gearbox ratios. At best, a compromise setting covers most corners. The worst-as I would learn from conversation with riders-is either an upsetting rapid cycling of engagement or enough force on the rear tire to make it slide out as the decelerating bike leans over entering turns.

All admire Ducati’s challenge to Honda, which was once Yamaha’s role. That company was last consistently at top level when Wayne Rainey was racing 10 years ago. GP bikes are designed by riders, not by engineers-and certainly not by computers! Engineers implement what strong riders ask for. Mick Doohan did this for Honda in the 1990s. He proved that if given what he requested, it would translate into race wins. Such trust is bi-directional-by the factory that the rider will go faster with his requested changes; by the rider that the factory will keep the bike’s best features, changing only what needs it. Since Rainey’s paralyzing accident, no equally forceful rider partnership has emerged. Hence Yamaha’s cost-is-no-object campaign to recruit Doctor Rossi for 2004.

Question: Since Valentino has always ridden developed machines, can he hope to provide R&D direction to a new employer? This could be a new interest for Rossi, a new challenge for a rider with three straight world championships on overdog machines.

The Hondas accelerate very hard, their harsh sound barking out loudly. KR says, “Just look at where the Hondas are shifting, and then look where everyone else shifts.” I did, and it was just as he’d said-the Hondas shift significantly earlier. Kenny goes out on the circuit to watch: “If I don’t like what I see, I come back and tell ’em.” Was there ever a doubt?

Quietest are the Suzukis, with their long, Superbike-style mufflers. This company began an ambitious MotoGP program using its 500cc two-stroke chassis team. When months of effort didn’t reach goals set for complex automatic controls, higher-ups put in younger men, hoping for fresh ideas. The young guns had to retrace the steps of the others, taking up more time. It may be that Suzuki can’t cover the bet it has made on F-1 -inspired technology. Robot bikes are not yet ready for primetime.

Surprise? I was invited to a small press conference given by Honda engineer Mr. Kanaumi, former Superbike racer and first man to ride the RC211 VFive. A European journalist asked the usual question: Does Honda and Ducati’s success come from their Formula One access? Kanaumi waved this away, saying that so far, the fastest motorcycle is the one most conventionally easy to ride. “Our machine is not the best in every category of performance,” he began, “but we have worked hard to make the best all-around package-a riderfriendly machine.”

Former GP star Randy Mamola notes that the Yamaha has the quickest steering. The Ducatis make outstanding starts (other riders covet the Ducati clutch) and-at least at the start of the season-had the highest top speed. But the unique fact about the Honda is that many different riders, some of them without 500cc GP success, have been able to ride up front on it. It just does what it’s told and does it well. Mamola, having ridden both the Honda and Ducati, says, “I smile, I laugh in my helmet because the power is so smooth!”

I asked Kanaumi about his RC-V design team. Large? Or small?

“Small team. If big team, no one takes responsibility. Also, no one can agree. Too many meetings,” he said. I’d heard the same at Ducati! Later I would hear that senior Honda engineers-the nowretired Mr. Oguma, Mr. Fukui and Mr. Abe-all send their people to technology museums like the U.S. Smithsonian or Germany’s Deutsches Museum. One of them was quoted as saying, “Honda Motor has only had three big ideas. For the rest, you must look to history.” This pleases me, for I know that in many companies, computers rank above ideas, and concepts more than five years old are too often ignored.

The high-rewing Ducatis are off their usual pace here-Motegi is Honda’s test track and the Desmosedicis are spinning and looking unstable. Yet others have learned much from Ducati, whose Superbikes proved that unstable-looking wallowing can be associated with outstanding grip, what Colin Edwards calls “digging.” This is chassis flex at work, taking over the suspension’s job at high lean angles.

Is everyone using high-tech anti-spin? No, both Ducatis are painting darkies off this turn-even hitting their rev-limiters-and losing time. Other hard-accelerating bikes are making the woo-woowoo sound of wheelspin too, especially the revvy Aprilia. Race-goers have thrilled to this spooky sound since the days when Yamaha TZ750s were winning races.

Reams of press releases are generated at the races. Here, every team, every sponsor, every accessory-maker has staffers furiously typing and e-mailing in one of the 60 portable offices behind Motegi’s 500-foot pit building. This is an “away race,” but in Europe there would be 100plus tractor-trailer transporters in this space. Only a few of these big rigs have anything to do with actual racing. Tenwheeled hospitality suites expand under hydraulic power to host the powerful persons who must be cosseted so that the future may continue to unfold. What is racing coming to? One day, I predict, a team may through clerical error neglect to bring the one transporter that actually contains the racebikes. It won't make any difference-the haplessly optimistic press releases will still flash over the In-

ternet and the champagne will continue to bubble.

Down at the end of the paddock is the "historical section," with its two-stroke 125s and 250s. I walk down there several times a day for a quick "smoke," and to hear the sound of GP racing as it once was. All GP bikes are beautiful-gorgeous welds, elegant curved radiators, ti tanium pipes. I take a stroll through the back of the fourstroke pits. Hanging casual ly from a box are four sets of priceless titanium 4-2-1 pipes for the Yamaha YZR Ml. The shipping containers for the Proton team have strange shapes, dark mono liths like props from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Fuel and spray solvent perfume the atmosphere. Air hoses blow parts clean and dry.

The Yamahas and Hondas have fluttery, very fast idles once they are started, but the desmo Ducatis, because they have no valve springs, don’t need to rev to keep their cam lobes from galling. When their throttles are snapped, they bark suddenly, making a sound like a pile-driver’s impacts. I hear the whine of an external starter and a Yamaha comes to life.

Practice resumes and the Kawasakis break up at higher revs. A year ago, Kawasaki and Suzuki spoke of selling engines

to private teams in 2004. No more. Rossi is methodical, waiting for his engine to warm and run smoothly, scrubbing new tires, then going very fast. As bikes roll off this corner, their revs at first fall in-

stead of rise-the effect of rolling-radius increase as the tires rise off their short sidewalls.

Some MotoGP bikes (no top ones!) have tiny, F-iderived carbon clutches, and riders are unhappy with these floppy-disc-sized won ders. Carbon's friction lev el rises steeply with tem perature, making smooth, strong starts difficult. For mula One cars have the abundant grip of wide tires. The motorcycle problem is to transmit forces through much less rubber. F-i tech is wearing thin here.

Remember corner-exit high-sides, scourge of the late 1980s? The steep torque of 500cc two-strokes, corn bined with high-peak-grip rubber, made corner exits into a series of short, sharp slides-too often terminated

by a snap high-side that sent the rider fly ing. Today, smooth four-stroke torque has banished that but put a new problem in its place: braking instability. Braking leaves little weight on the back tire, so any lack of smoothness in en gine-braking control breaks rear-wheel grip. makIng the back of the bike waggle 1mm side-to-side. This carl grow \ 10lent, throwing bike and rider on the ground.

The pits are full of fans. Spectators crowd up to the backs of the garages, hoping for a glimpse or a word when a favorite rider makes his dash for freedom. Mamola, long retired but like Doohan now a fixture in the sport, dutifully signs autographs. This is a hard life, requiring endless energy-putting this city into boxes so it can be built again in Malaysia next week, and in Australia the week after. Fit-looking 30ish team members, many with skinhead haircuts, look like soldiers in some grim Special Forces unit. By Sunday at 8 p.m., all that remains of the teams are silent clusters of shipping containers in each pit. Boeing 747 freighters are waiting, and rental vans full of crewmen are on their way to airport hotels. These are citizens of the world, constantly rubbing elbows with others from all nations. Their news comes not from TV but from people who’ve been there, so conversation with them is refreshing and full of surprises.

The race itself was almost incidental, since only miracles of good and bad luck could sustain Sete Gibemau’s challenge to Rossi. Then Rossi made two of his unexplainable “mistakes.” Or does he run off now and then just to make racing more amusing for himself? Running second behind leader Max Biaggi, he rode off into a gravel trap, rejoining in ninth. Through the field he sliced to finish second, with Nicky Hayden (who has earned the respect of the MotoGP paddock this year) a popular third. Another day, another sensational Rossi performance, on his way to yet another world title.

MotoGP is not real racing yet. That will require more competition than Ducati’s occasional third, or a Yamaha or two somewhere in the top 10. And the others? Theirs is another, lesser race, run concurrently. All the same, the scene is pregnant with discussion of ideas, and with the hardware those ideas imply. It was

1 1 i 1 r*n

hard to leave.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year

February 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsLost Summers

February 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSuperbike Situations

February 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2004 -

Roundup

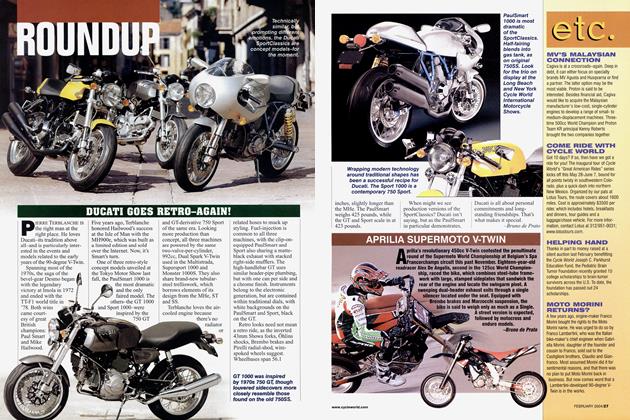

RoundupDucati Goes Retro-Again!

February 2004 By Bruno De Prato -

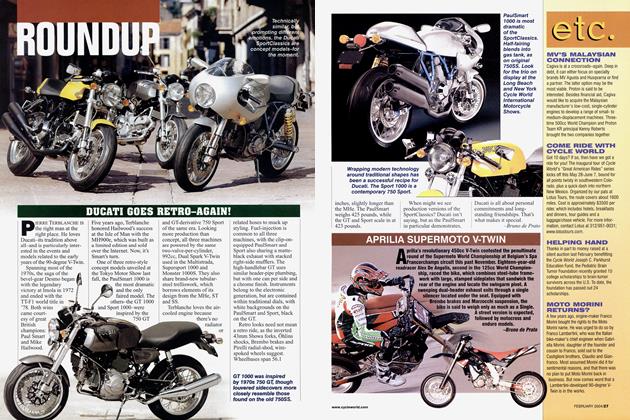

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Supermoto V-Twin

February 2004 By Bruno De Prato