PLUCK OF THE IRISH

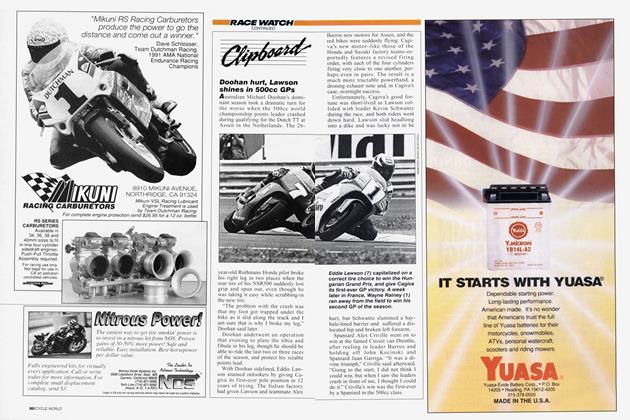

RACE WATCH

Fear factor? What fear factor?

GARY INMAN

"IF YOU SEE A STATIONARY YELLOW FLAG IT COULD mean there's a broken-down bike, a person or tractor on the track. If the flag's waving, the tractor may be moving."

Welcome to Athea, the Irish village that's home to one of the newest events on the "Real Roads" race calendar. The paddock, a slanting farmer's field, is packed with vans, motorhomes, a couple of T-shirt stalls, a burger van, an inflatable sign-in office and a slurry spreader. There are also a hundred or so racebikes, from a classic Motobi Single with an exhaust note like an atomic bon go drum to ex-Nobby Ueda Honda 250s and British Su perbike-spec Yamaha YZF-Rl s.

You've got to have a good map of Ireland to find Athea (pronounced Ah-tav). Located in a valley not far from the border of counties Limerick and Kerry, it's a fairly typical, not unattractive place that was unremarkable in almost every way. That is, was unremarkable.

CONTINUED

Three years ago, local enthusiasts and small business owners decided to give Athea something to be proud of: a road race. It was a risk. It's not cheap to or ganize and promote a national-level event. And, as there are no other road races this far south-the majority being held in Northern Ireland-there were no assurances anyone would come to race or spectate.

Despite what you may have heard, for tune doesn't favor the brave. The first year was rained out-a complete, demoralizing washout. Bloodied but unbeaten, the show went on and last year's event was a great success. Despite the presence of dark clouds, this one looked even bigger.

Saturday was practice day. "The road will close at 11 a.m. sharp. Or maybe 12 noon," we were informed. There was a shortage of flag marshals, so friends and sponsors took on the duties to help get things moving. I asked old hands if this was a regular occurrence in Irish roadrac ing because not a single complaint had been aired. It was not. Marshals are nor mally organized in advance, but Athea had been let down. There was no moan ing because "real" roadracers are far more laid-back than their circuit-racing brethren. Whatever, no hurry, it would all happen when it happened was the atti tude. In the end, it was close to 1 p.m. be fore the first bikes rolled out for practice.

They took to a circuit that is roughly a square: four straights with right angles at the corners, a complex of bends near the village, a chicane and an insane uphill, flat-out, left-hand kink leading toward a blind brow. More than 4500 haybales lined the 3.3-mile course. Wrapped around fence posts, pushed up against walls, tied to trees and lampposts or dumped in piles near newly built houses, they were golden-yellow organic reminders of racing’s dangers.

The bales are little more than token gestures. This thought occurred to me as I stood in a turnout at the side of a straightaway. A moment later, three 250s came past so quickly and so close to me that they flapped the bottom of my Levi’s. And I wasn’t standing in a privileged photographer’s position but in a spot where anyone could park his arse. If you like racing up close and personal, there’s no better seat.

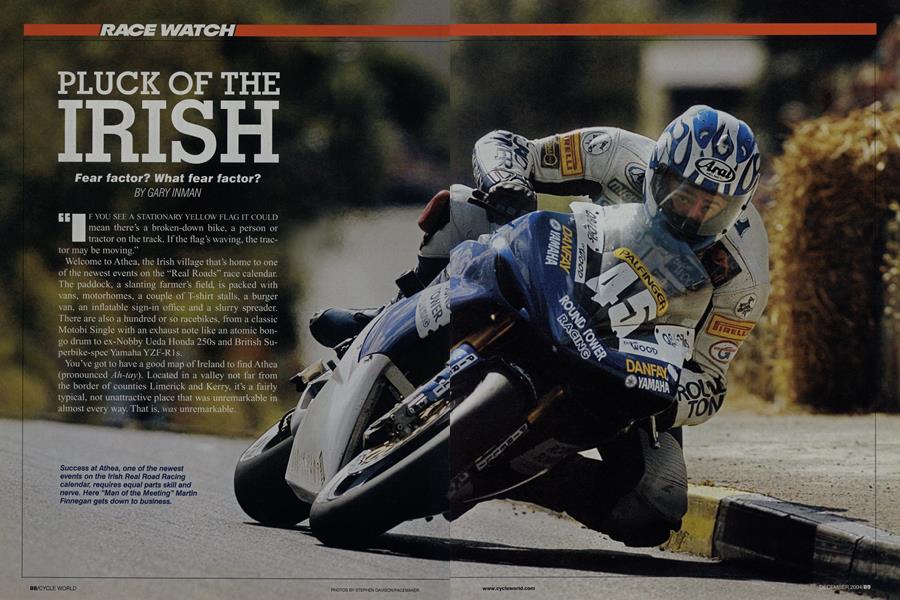

Back in the paddock, I talked tactics with last year’s Athea Man of the Meeting, Martin Finnegan.

“The back straight is so narrow I’ll have to pass on the grass,” he said. “If I’m in front, I’ll have my elbows out to make myself as wide as possible. Or I might pull to the side and kick up some dust.”

The straightaway he described is ridiculous. It’s about as narrow as the average suburban driveway, but heavily cambered.

CONTINUED

Then add a slowly decomposing surface that makes the riders’ eyeballs wobble ferociously. Oh, and 2 feet of runoff on each side.

A chicane-the Mid West Tarmac Chicane-was added to slow the pace on the straightaway. But the top Open-class riders still touch 180 mph before braking. This is a circuit geared for bikes that have come straight from the high-speed Isle of Man TT.

Race day dawned gray and damp. The sound of organizers’ hearts dropping was louder than cannon fire over the Western Front, but by the time the roads were closed-on time-a light wind had blown in fluffy white clouds.

In the paddock, a riders’ meeting was called and a short list of names was read out. Theses were the competitors, supposedly picked at random, who were required to take a Breathalyzer test. “Roadracing was more fun before the breath tests,” fretted Robert Dunlop, who had been banned in the past for failing such a test.

A plump schedule of 13 races meant some classes had their events cut from eight to six laps. Even with that concession, the starts were going to have to come thick and fast-bang, bang, bang-like hammer blows. The start of the race card wasn’t promising when in the very first corner of the very first lap, two bikes came together and a restart was called. Fortunately, neither rider was hurt.

One by one, the races were flagged off. The 125s, their riders bent like paperclips, bounced up and down on the bumpy straightaways. Between races, there was just enough time for the crowd to walk 100 yards along the "track" to another vantage point. Then the classics flew through. From my position at the edge of the road, they were painfully loud. Mega phone exhausts belted out Singleand Twin-cylinder drumbeats that reverberated off the plate-glass windows of gas stations and the walls of the community center. People screwed up their eyes as the thick sound waves slapped them around the face.

The 600s took to the track for the first of the real high-speed races. All the “names” made the long drive to Athea. The field was released from the grid by a wave of the Irish tricolor in clumps of six, four or three-not one at a time like the TT.

Raymond Porter, riding a Suzuki GSX-R600, led the field. This time I watched from a grass bank opposite the pits, my head literally between bushes and hedges. As the first four bikes passed, I felt the breath being sucked from my lungs. I was closer to the action than a pit wall is to the edge of a Grand Prix track. That close to the road, it was almost impossible to swivel my head quickly enough to track a bike’s flat-out progress as it passed by an arm’s length away. Darran Lindsay pipped Porter at the flag, with Finnegan in third.

Ryan Farquhar, recovering from an injured wrist, was fourth and not instantly recognizable to the casual observer. Instead of riding the purple-and-green Winston McAdoo-sponsored bikes he campaigns at the TT and the North-West 200, he was on a pair of black-and-orange Harker Kawasakis. His long-time sponsor McAdoo is a strict Sabbatarian and does n't allow his bikes to be raced on Sun days. That would curtail a British Super bike rider's career prospects somewhat, but when it comes to real roads racing it isn't quite the absurd arrangement it sounds. In Northern Ireland, all roadraces are held on Saturday with practice taking place on Friday. To allow him to race in the South’s Sunday events, Farquhar has an additional sponsor that supplies him with bikes. That way, everyone’s happy.

The 600 race was fast. But the Open and the Grand Final, when the tuned 1000s took to the track, were truly aweinspiring. If you've witnessed the TT in the flesh, an event like Athea won't be shocking, but it will delight any fan of motorcycle sport. It's heartening to know there are still places in the world where a few individuals can get together, raise the money for insurance and emer gency helicopter cover, rustle up some prize money and have some of the very best racers in their respective fields ride 200-horsepower inline-Fours like holy hell for eight laps.

- _~-~1 CONTINUED

CONTINUED

There were people kneeling in flowerbeds who had never seen a motorcycle race. They paid for a program and admis sion and were watching the broad-shoul dered Finnegan chase down Farquhar in the last race of the day. Finnegan got a poor start, but by the halfway point he was in touching distance of the lead Kawasaki ZX-1OR as the two nailed it up the hill and over the starting line. The track commen tator could only see an eighth of the track, so when the racers went out of sight, no one had any idea what was happening. When the bikes reappeared around Gables Corner, Finnegan had such a lead I feared Farquhar had crashed. Then he flashed into view, knee down.

“I was just watching where I could pass, and when I did I knew I had to put in a fast lap,” Finnegan told me later. His fast lap, an incredible 113-mph average-7 mph quicker than last year-belied belief.

As Finnegan passed on his way to the win-knees in, hunched over the tank, head behind the screen-a 12-year-old kid stood on a fence pumping his fists.

Irish roadracing may be an anomaly, viewed by many as a dangerous minority sport for those who can’t cut it on the short circuits, but in Athea it really matters. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

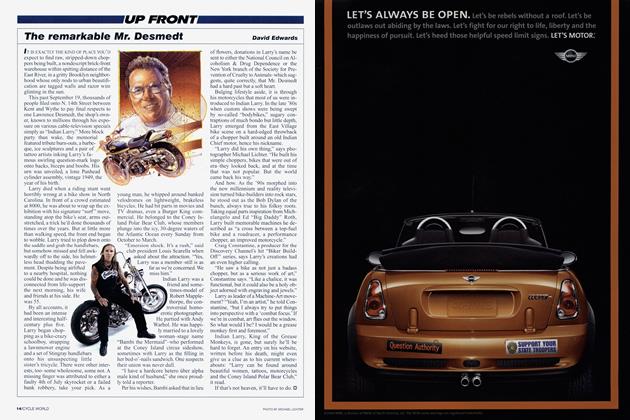

ColumnsThe Remarkable Mr. Desmedt

December 2004 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsA Minor Odyssey

December 2004 By Peter Egan -

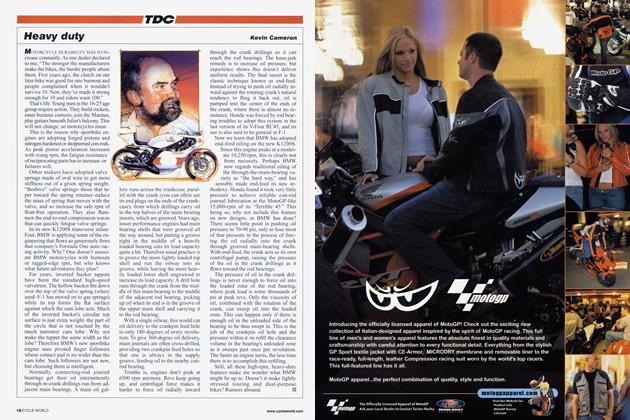

TDC

TDCHeavy Duty

December 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2004 -

Roundup

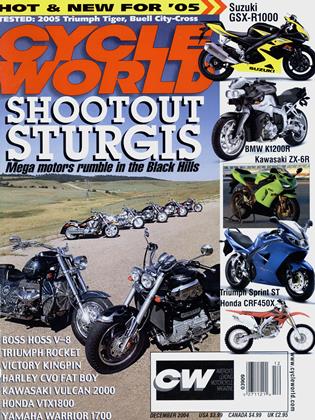

RoundupAll-New Suzuki Gsx-R1000!

December 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMoto-Street Suzuki

December 2004 By Mark Hoyer