THE WHY OF ROADS

An Ode to Asphalt

JAMES R. PETERSEN

WHO BUILT THIS ROAD AND WHY?" PART GRATITUDE, PART wonder, part escalating joy, the question is one I've encountered at rest stops on the best rides of my life. Someone pulls off his helmet, catches his breath and gives vent to pure curiosity—you know, the kind captured in the phrase, “Who was that masked man, anyway?”

I first encountered this respect for the unknown maker of roads at a dinner in Monterey, California. My late friend Slick Lawson was rhapsodizing about his favorite ride back in Tennessee. “The Natchez Trace,” he said with the appropriate Southern drawl, “was designed by an oldtime surveyor with octagonal glasses and lace-up boots, a man who used a brass transit to create the perfect ride, a melody of concrete with no offcamber turns.” Slick talked like that, but I accepted his invitation to come to Nashville and see for myself.

The road delivered. If a more perfect two-lane road exists, I don’t know its name. The Trace caresses hills, leaps across gorges on high bridges, dives and soars along ridges, all within a canyon of green, its wide parkways home to zigzagging split-rail fences that call up the ghosts of Confederate soldiers. And without a strip mall in sight. At the time, I wrote that this band of perfect asphalt was like the glimpse of a long-legged woman in a slit skirt. Eternal promise, the gaze being drawn to a point in the distance.

Only drawback to the ride was a strictly enforced speed limit. Slick warned that if the rangers catch you going much over 45, they put you on road-kill duty, scraping up dead animals with a spatula-or if they’re still alive, “raccoon relocation.” I wondered if the federal government would consider a new income source, renting out the Trace for one-way, 444-mile sprints? Hey, they close half of France so Lance Armstrong can date Sheryl Crow!

I found myself looking up the history of the Trace, trying to identify the mythical surveyor conjured up by Slick. Natchez Trace Parkway follows the meanderings of an ancient trail that, according to easily accessible websites, connected southern portions of the Mississippi to salt licks in central Tennessee. Salt licks?

In the early ’30s, Jim Walton, an “itinerant piano tuner, amateur journalist, self-styled colonel and International Hobo,” devoted his talents to the Trace at the request of the Daughters of the American Revolution and set out to “substantiate its actual route.” He formed fake committees, something called the Natchez Trace Military Highway Association, and began to petition Congress for funds to pave the road.

The project began in 1938. In 1996 Washington completed the final strand, declaring it a “National Scenic Byway and All American Road.” Cool. I owed one of the best rides of my life to a piano tuner, schemer and seducer of daughters of the American Revolution. If motorcycling needs a patron saint, he’s the guy.

I next heard the “Why of Roads” question on the press intro for the new BMW R1200GS in South Africa.

We’d spent two nights at a luxury hotel on the estate of the engineer who opened up the interior, riding dirt and gravel roads through the mountain passes he'd mapped, following switchbacks still supported by stone embankments, each rock hewn and placed by hand.

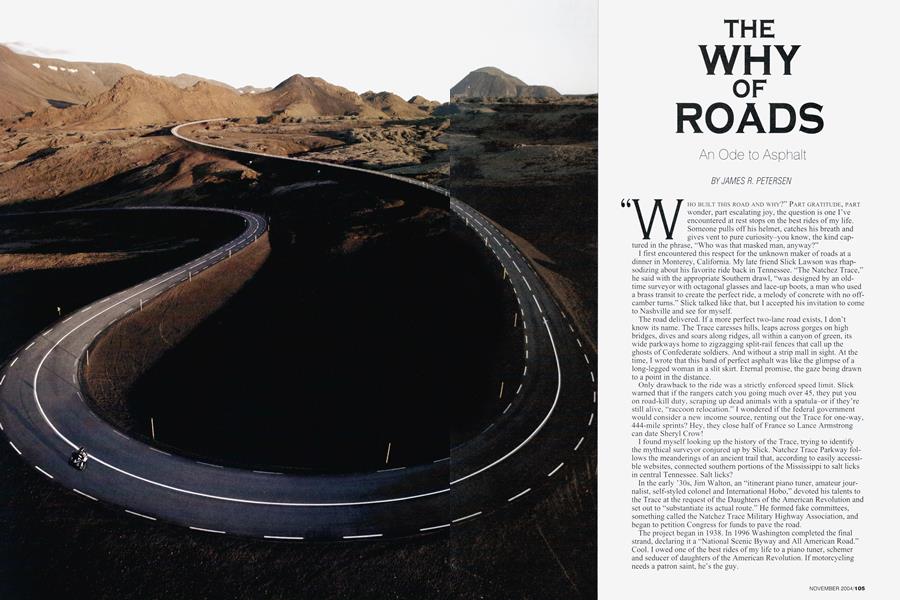

So maybe the ghost of the builder of roads was in the air when we hit Chapman’s Peak Drive, south of Cape Town. Carved into the side of a mountain, the tight, winding ribbon of asphalt was like a bonsai tree-a miniature that calls up the ideal. On one side rock, on the other a 1500-foot drop into the dark waters of the Atlantic, above the kind of blue sky you haven’t seen in America in decades. Imagine your favorite stretch of Pacific Coast Highway near Big Sur, made immaculate. As we entered, crews of Africans were busy sweeping the asphalt surface with brooms, as though it were an heirloom.

We rode this perfect surface through crisp morning air, beneath steel nets that protected from falling rocks, through half-tunnels and around tight coils of stone. It was a short ride, almost like a kart track, barely 10 kilometers, but there were no objections when I asked if anyone wanted to turn around and do it again.

Again, this was the kind of road you wanted to keep in a velvet case, like a vintage guitar or a set of dueling pistols. It was a 12-bar melody, fluid enough that you had attention left over for the view, which was again, the incredible wild Atlantic and then the calm water of Haut Bay, home to a fishing fleet, the ruins of an old fort. Freelance writer Jim McCall whispered the question, full of awe and wonder, “Who the hell made this road and why?”

The history? In 1915, Sir Frederic de Waal, Administrator of the Cape, called for the construction of a road connecting Cape Town with the Cape of Good Hope. He believed that “tourists would one day abandon Egypt and spend three months of the year in Cape Town.” So Waal spent $15 million to build a road that surely is one of the wonders of the not-soancient world, all to compete with the Pyramids. Hey, wish you were here.

On an off-road tour of Death Valley, California, I careened up a mere suggestion of a road-more of a goat path, really-to Aguerreberry Point, a promontory more than a mile above the valley floor. Looking to the east we could see the Funeral Mountains, white clay beds, salt marshes, alluvial fans, the kind of stuff that gave Ansel Adams wet dreams. And colors! Pink, lavender, brown, exhausted shades of gray and black that inspired him to experiment with Kodachrome. A plaque said the point was named for the prospector who built the rough road to show off his favorite view of the valley. We stood looking out at layered earth, folded and uplifted in wild array; focused again on tiny flowers, listened to the wind and when it died, the absolute silence. Thanks, Mr. Aguerreberry.

I don’t always ask the question out of curiosity or reverence. I have a picture of Italy’s Passo Dello Stelvio

on the wall of my office. It shows a jagged line of switchbacks, like the tracings of a lie detector ripped out of the machine and draped across a mountain. If you get the rhythm right, it is a soothing ride, an act as unconscious as tossing a salad or closing a gate. If you get it right. I’ve dropped motorcycles there twice, and asked the obvious, “Who the @#$% made this road?”

Roads like this are Werner Wachter’s playground. Head man at Edelweiss Tours, for years he’s led groups of motorcyclists up ancient mountain passes, built when man was driven by the desire to trade. (Wanna try some of my purple berries? Yeah, they’ve been stepped on. You can have the whole basket in trade for your daughter. Okay, what about that truffle-sniffing hog?)

I’ve learned to tell the age of the road by the details-grades are set for ox, horse and human energies, not the internal-combustion variety; hairpins are carved on the turning circle of an oxcart; inns and restaurants are placed halfway up a mountain because that was as far as the animals could go in a day. And then someone came along and laid asphalt along these old paths. On the Passo Delio Stelvio, I suspect it was gnomes who knew that one day there would be motorcyclists, that they could then harvest metal from the footpegs, exhaust pipes and cylinder heads of BMWs, then forge the ring of Sauron or some such evil magic.

Any combination of bike and road can inspire curiosity. Take the ride out to Sturgis.

As far as routes go, it is pretty simple. Head north from Chicago.

Turn left. Turn right.

You’re there. Now get drunk and fall down.

To whom do we owe the Interstate highway system?

In 1919, a young Dwight D. Eisenhower joined the first transcontinental motor convoy. The trip took 62 days, average speed 6 mph. According to Ike, vehicles sank in quicksand and mud, ran off roads that “varied from average to nonexistent.” The troops, he relayed, “colored the air with

expressions in starting and stopping that indicated a longer association with teams of horses than internalcombustion engines.” Well, the language hasn’t changed.

Thirty years later, President Eisenhower called for the building of a national network of roads. The technical name is “Military and Interstate Highway System.” The limited-access concrete ribbons are part of a World War III weapons-delivery system, intended to funnel troops and material quickly.

There is some nascent memory of the origins of these highways, urban myths claiming that one out of five miles of every Iroad has to be straight so that SAC bombers can land after a first strike obliterates their home base. Not true.

But I have heard accounts of bikers watching B-52s doing practice landings on the interstates out in Wyoming. Or maybe they were UFOs.

Boredom and 48 hours in the saddle of a Harley can drive you to visions.

Switch from Speed to the History Channel and you develop an appreciation, an understanding, that our sport is about more than just the motorcycle.

James R. Petersen is a contributing editor for Playboy. where the photo shoots are almost as much fun as Cycle World’s.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Accidental Sport-Tourist

November 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKtm Unplugged

November 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBigger Big Bangs?

November 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2004 -

Roundup

Roundup2005 Bmw K1200s: Too Fast For the Autobahn?

November 2004 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Goes To Motogp

November 2004 By Bruno Deprato