BONE ShAKER

American FLYERS

A BSA back from the dead

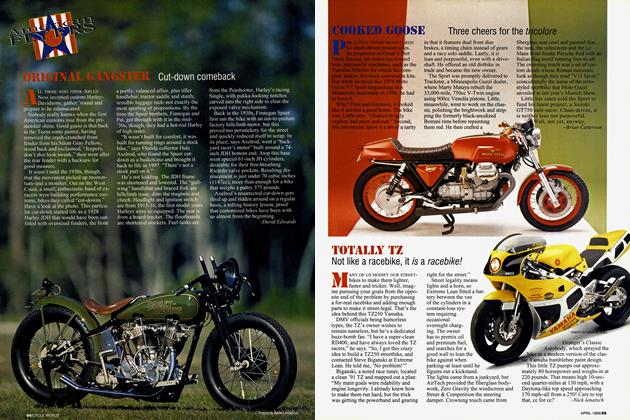

LD-SCHOOL CHOPPERS get a bad rap, seen as spindly, evil-handling relics from the cannabis clouded Age of Aquarius, poor unsuspecting classics upon which unspeakable acts were perpetrated. Bull.

The choppers of the late Sixties and early Seventies laid the groundwork for today's thriving, billion dollar afiermarket industry. Sparked by the popularity of Peter Fonda's biker epic Easy Rider, the chopper movement soon became a juggernaut. Everybody wanted one. Where before there was the backyard customizer armed with a hacksaw, a blowtorch and foggy intentions, now came companies catering to the needs of new riders wanting to give their Triumphs or BSAs or

Hondas or Harleys the requisite chromed, kicked-out custom look. Perry Sands, main man at Performance Machine, got his start welding up springer forks before segueing into chopper brakes, and-unlike many of those present-vividly remembers the era.

“It was a time before CNC billet parts, so you had to be pretty good with the tools of the trade-welders, bandsaws, etc.-and to stand out you had to be creative,” he says. “It’s fair to say that many current companies wouldn’t be here today if not for the start the chopper craze gave them.”

Other surviving firms from the dawn of the longbike? The list is long:

Corbin Saddles, Kosman Specialities, Hallcraft’s, Arlen Ness, Paugho, Jardine, Forking by Frank, among others.

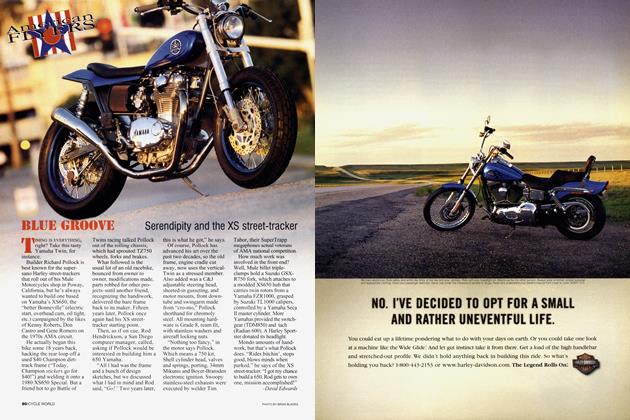

Don Miller’s 650 BSA shown here is a tribute to those days and the chopper’s place in moto-history. But the man who heads up Metro Racing, supplier of vintagelogo motorcycle T-shirts and jerseys, didn’t need any storebought help in bringing this rolling basketcasc of a Beezer back to life. A former career restoring bikes and cars meant Miller had all the skills necessary; in fact, short of the tires, seat leather and the teeny skeleton hanging onto the headlight rim for dear death, the 40-year-old Pennsylvanian handcrafted every piece of this machine. He also painted it and lettered the gas tank-apparently the “Reptibate” moniker is Cajun slang for someone you might want to feed to the ’gators, as in reptile bait.

The bony hands grasping the gas tank and supporting the alloy rear fender (originally on a Bultaco Alpina!) certainly stay on theme. Working from an X-ray, Miller crafted them from steel rods of varying thickness, using brass to build up the knuckles. The finished claws were nickel-plated, then spayed with black paint and quickly wiped off for the proper distressed effect.

Everywhere you look on this bike, there arc treats for the eyes. The flat-track-style Joe Hunt magneto complete with clear plastic cover so there’s no doubt when sparks are flying. The subtle flames bead-blasted into the primary cover’s aluminum. Indian twistgrips on both handlebar ends-one running the throttle, the other the clutch-so the control cables remain mostly hidden. The, cr, repurposed kickstart lever (“That’s a ‘paperweight’ I bought on the Internet; brass knuckles are illegal.”). Even the oil tank’s dipstick has surprises, fashioned from a dagger with the words “Jesse Who?” engraved on its blade, a good-natured jab at the West Coast’s celebrity chopper builder/cable-television star.

Two years in the remaking, Reptibate now takes its place among Don’s other bikes, including a chrome-framed Bultaco Astro short-tracker and an authentic Indian 101 Wall of Death bike.

“I’m not a black Softail kind of guy,” he says.

No bones about it.

David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontIssue No. 500

August 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiding the Cheyenne Breaks

August 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPressing Matters

August 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Department

DepartmentHotshots

August 2003 -

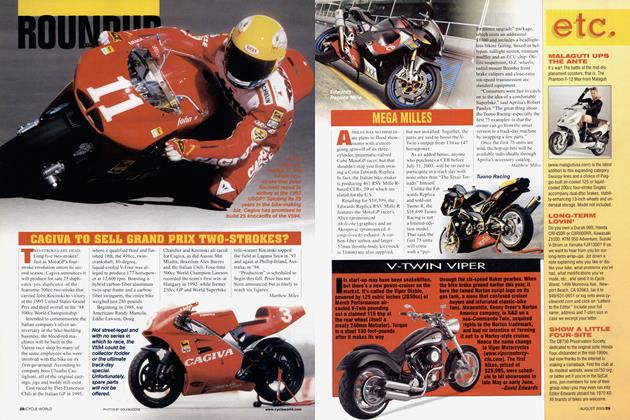

Roundup

RoundupCagiva To Sell Grand Prix Two-Strokes?

August 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupMega Milles

August 2003