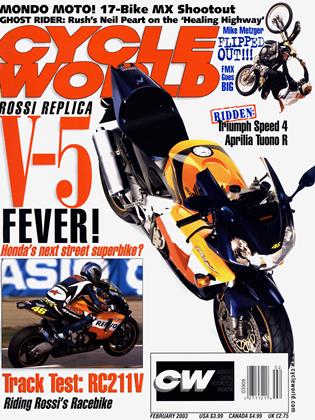

V-5 FEVER

SUPERPOWER

Honda's RC211V and the New World of MotoGP

KEVIN CAMERON

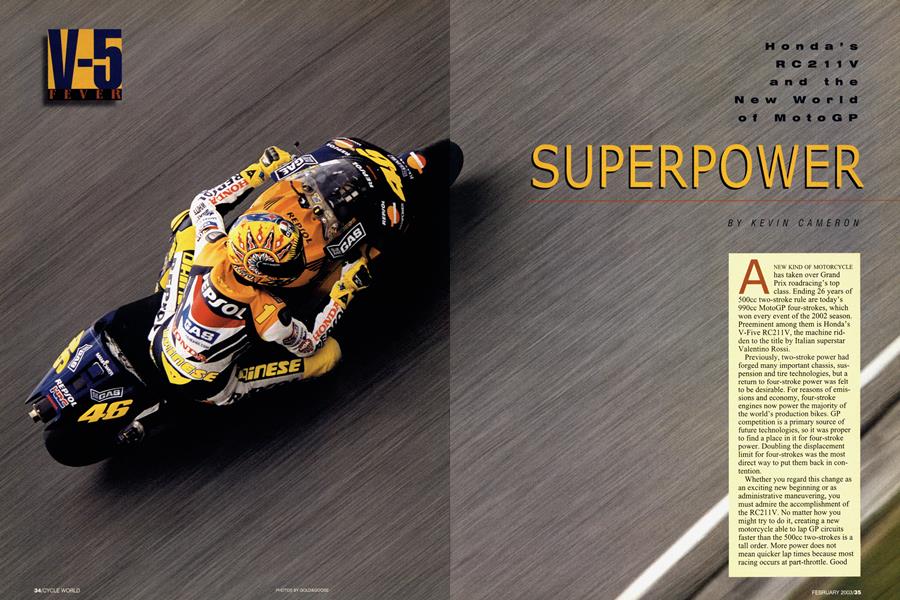

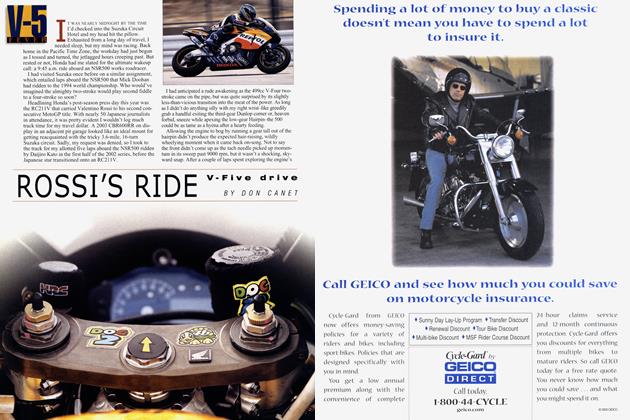

A NEW KIND OF MOTORCYCLE has taken over Grand Prix roadracing's top class. Ending 26 years of 500cc two-stroke rule are today's 990cc MotoGP four-strokes, which won every event of the 2002 season. Preeminent among them is Honda's V-Five RC211V, the machine ridden to the title by Italian superstar Valentino Rossi.

Previously, two-stroke power had forged many important chassis, suspension and tire technologies, but a return to four-stroke power was felt to be desirable. For reasons of emissions and economy, four-stroke engines now power the majority of the world’s production bikes. GP competition is a primary source of future technologies, so it was proper to find a place in it for four-stroke power. Doubling the displacement limit for four-strokes was the most direct way to put them back in contention.

Whether you regard this change as an exciting new beginning or as administrative maneuvering, you must admire the accomplishment of the RC21IV. No matter how you might try to do it, creating a new motorcycle able to lap GP circuits faster than the 500cc two-strokes is a tall order. More power does not mean quicker lap times because most racing occurs at part-throttle. Good lap times are achieved during comer exit. Stopwatches are impressed by a machine that comes off comers exactly at the limit of what the tires can handle. Spikes and dips in the engine’s torque curve make this impossible; the rider must throttle back to keep the spikes from breaking tire traction. He is passed by the man whose power is smoother-regardless of how much peak power each bike makes.

Once the machine is near-upright after a comer, and tire grip is no longer monopolized by cornering, a new limit appears: the wheelie limit. Up to about 90 mph, full throttle just lifts the front wheel. Most of the racing on GP circuits takes place under these conditions, with little time spent above 90 mph where more power could actually be useful. The game, therefore, is to shape the engine’s part-throttle torque into a smooth, flat tool that the rider can always match closely to prevailing conditions. This is what riders mean by their phrase “throttle connection.”

More power usually means a bigger, heavier engine, which in turn requires a heavier chassis and more powerful brakes, with a bigger “wind-blocker”-the giant radiator necessary to dissipate the engine’s greater heat flow. In AMA roadracing, “little” 750cc Superbikes lap faster than unlimited Formula Xtreme bikes. Why so? Because the extra mass of bigger engines destroys more performance than their power potential can create. Intensive development has smoothed the torque of 750s, while F-X torque still displays bumps and dips.

These are the reasons why Honda’s accomplishment with the RC21IV is so remarkable. It has a lot of power-estimates run from 220 to 250 horsepower, or 15-30 percent more than the 500s-but that power was not hard to create. What Honda has done is to fit that power into a manageable package, and to take throttle connection to a new level.

Other things being equal, the bigger the motorcycle, the harder its front tire must work in turns. In GP racing, the 125s have the highest corner speeds. Then come the 250s, which are often 10 percent faster at the apex than 500s. The 500s themselves are a special case, as Valentino Rossi notes elsewhere in this issue, because the roughness of their power makes it safer for the rider to adopt what Rossi calls a “stop and re-start” style in comers. The 990s, because their power is so smooth, can be ridden closer to their comer speed maximum. Why not just make front tires big enough to make 990s turn like 125s? Until there exists motorcycle power steering as sensitive as holding the front axle in your hands, front tire size is limited by rider strength and the need for quick response. To use the acceleration potential of bigger engines, they must be mounted forward as they are in dragsters, to keep wheelies from limiting that acceleration. As weight is added to that front tire of limited size, the harder it must work at the apex. Honda had to cancel that deficit with some other benefit of greater effect. We are talking here about improving a delicate balance that has taken 26 seasons of 500cc two-stroke racing to achieve. No simple matter.

The major advantage of the four-stroke is that its power, as the throttle is initially opened, begins near zero and increases smoothly, especially in mildly tuned engines with short cam timing. In the two-stroke this is not possible, because at low throttle, fresh charge is so diluted by exhaust gas left from the previous cycle that it cannot at first be ignited. When it fires, it does so only after several cycles have delivered enough charge to be ignited. Torque therefore increases in chunks as eight-stroking becomes fourstroking, and four-stroking jumps to steady firing-torque doubling at each step. Devices such as exhaust powervalves have helped, but this problem has never gone away. Therefore a rider on a four-stroke can safely send power to the rear tire sooner in corners, and so begin acceleration earlier. As an example of how well this can work, note that existing 350-pound 750/1 OOOcc World Superbikes have come very close to the lap times of the 286pound 500cc GP bikes.

The big performance advantage of the two-stroke has always been its very high power-to-weight ratio. The FIM has now allowed four-strokes to at least equal this by doubling their displacement. With power thus within reach, the task was to combine the extreme off-the-bottom smoothness of a streetbike with the acceleration and top-end of a GP bike. The design couldn’t be allowed to swell into lumberwagons like the old 1025cc Superbikes, because such giant motorcycles abuse tires and riders. What was needed was a one-liter four-stroke motorcycle, condensed into two-stroke size and responsiveness, with 50 percent more power than the old 1025s, yet with streetbike smoothness off the bottom-and make it successful from the first flag.

Rules allow up to three cylinders at 130-kilogram (286-pound) weight, up to five at 140-kg (380-lb.), and any number at 150-kg (330-lb.). Honda chose the maximum number of cylinders in the middleweight category and built a V-Five engine. All five cylinders have the same displacement, and the crank has three crankpins. The two outer crankpins move together like those of a V-Four, but instead of the Four’s normal 90-degree Vee angle, the cylinders are closed up to 75.5 degrees to produce some imbalance. The motions of the fifth piston (which is in the front center of the bank) essentially cancel this imbalance.

Because the displacement is large, high-tech measures are not necessary to develop the requisite power. The engine might, for example, have an ordinary streetbike’s 1.6 bore/stroke ratio, so that 74 x 46mm dimensions would allow a moderately stressed 15,000-rpm power peak and 230 bhp-all with “vintage” metal valve springs. Again because the displacement is generous, it is possible to use the moderate valve timings that make engines come onthrottle smoothly from low revs. The engine is compact-Honda PR men tell us to think of it as “a sphere.”

This brings us to the chassis. In all its photography and videos, the 211 looks long, certainly longer than its new competitors. Yet we know that to turn quickly, bikes need short chassis-way back in 1935, Stanley Woods asked Velocette to build him a 52-inch TT racer, and Erik Buell still aims for this number. At the Munich Show, while heads were turned, 1 measured the 211 on view at 57.75 inches. Touring, anyone? But there’s a reason: The shorter the bike, the easier it wheelies, and the more limited its peak acceleration. If you have lots of power, you want to use it, so you make the wheelbase longer to keep the front wheel down and steering at a higher level of acceleration.

Fine, now what do we do about the slowed steering? Just as Dan Gurney did with his long, low Alligator motorcycle, we enhance one capability to compensate for a loss in another. The Alligator’s 60-inch wheelbase slows its steering, too, but to compensate, all of the machine’s mass is clustered tightly along its centerline, making it flick over quicker for turns. By making its engine as compact as possible (like a sphere?), by putting part of the fuel tank under the seat, and by other measures, the 211 has been given flickability. And, like the Alligator, the 21 l’s long chassis has raised its peak acceleration and braking levels.

Yamaha and Suzuki engineers spoke of how they had retained the proven geometry of their two-stroke chassis as starting points for their MotoGP four-strokes. At the time this seemed sensible, but now it appears only Honda considered the underlying physics. The problem was not to make a four-stroke as fast as the 500s, but to make it faster. Brute power would not have that effect, so some other basic change was necessary.

A recent problem has been suspension action (or lack thereof) at extreme angles of lean. A stiff chassis in a rough turn looks chattery and skittish, liable to slide unpredictably as micro-bumps keep the tires in the air. Normal suspension can’t handle this because it is specialized for the lower-frequency, larger-amplitude motions that can interfere with balanced sliding in turns. Therefore, chassis designers have resorted to the crudity of letting lateral flex perform this duty. Chassis longitudinal stiffness continues to increase, but look at recent Honda swingarm beams; they are extremely deep vertically, but quite thin laterally. Their depth keeps the rear wheel from twisting, which would introduce upsetting gyro kicks. Their lateral thinness allows the rear wheel to move sideways slightly, usefully helping the tire to accommodate high-frequency bumps. Crude? Yes, but the goal here is GP points, not elegance.

Considerable effort has been put into concentrating the mass of the machine close to its center of gravity, the goal being to reduce the machine’s “flywheel effect” once either end begins to slide. The fancy name is Yaw Polar Moment, and the goal is to make it small so that if the back end gets away, it takes minimum force and time to bring things back under control. Note that the engine is extremely short frontto-back, while the swingarm is more than 24 inches long.

Note also that Honda engineers have adopted an ultra-light carbon seat frame-previously an Aprilia signature feature. And so forth.

Well, that all sounds easy enough. Rapid prototyping machines will let us get castings back later this week, CNC machines will whip up the parts, and we should be ready to do battle next spring, right? Not quite. The above elements

can be identified and talked about, but what exact values of all the variables will give the best result, the result that is significantly faster than the existing 500s? Ah, well, we’ll just load the latest engine and vehicle simulation programs on our long row of Silicon Graphics workstations, enter the desired data, hit RUN, and sip our coffee. But wait-the sim programs were written last year, or the year before that, and we want to create the future, not the past. That means we have to build real prototypes, put them under real riders, test them, break them, redesign them, and test again. Testing gobbles money and time, but it finds

answers. Stop the meetings and start the work, put three shifts of our best people on this, issue red priorities for all the proto shops, even delay important production stuff while our R&D express train hurtles through. Rumor has it Honda set aside $ 150 million for the RC211V. It shows.

Does this represent a golden new beginning for GP racing? It may-if the other companies can compete. Is Yamaha really close now, as some believe? Ask Max Biaggi, who is bailing from the Yamaha team for his own RC21IV. It will be unfortunate if real competition does not emerge. Historically, Honda has treated racing as a risky public-relations problem, best solved by all finishers being on Hondas. Yet genuine competition creates interest in motorcycling as a whole. Single-brand dominance destroys interest by making results predictable. A bore.

Will the others catch up? It may be a matter of economics-which of the companies can comfortably afford the thousands of hours of testing, and which may be economically locked into the role of thirdraters, whose tired mechanics work desperately on half-completed bikes in swaying transporters on the way to races.

This year, while the mechanics of other brands were hard at work in their tents, Honda men knocked off at 5:00 and could be seen outside, talking on their cell phones. When the Hondas were rolled out and started up, they idled like streetbikes, and their mechanics left them running on stands and turned to other tasks. To paraphrase Suvorov, “Test hard, race easy.

Based on the numbers used by bankers to evaluate businesses, Honda looks in fair shape considering the sorry state of Japan’s economy. U.S. sales of Honda minivans and SUVs are brisk. The other Big Three look less healthy. Aprilia? Sharing its funding with the downfield three-cylinder four-stroke GP “Cube,” the previously impressive Superbike program wilted. Can Ducati keep two big red balloons fully inflated at once? Is there only one motorcycle superpower? We’ll see.

Meanwhile, cross your fingers that economies surge back to health, that the resulting cash flows cover the cost of racing at this much higher level, and that it all comes together in a glorious flowering of latter-day four-stroke competition.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year, 2002

February 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThem Ice Cold Blues

February 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring Fever

February 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2003 -

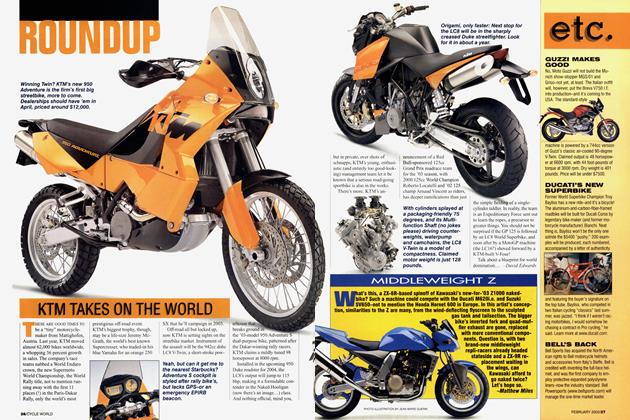

Roundup

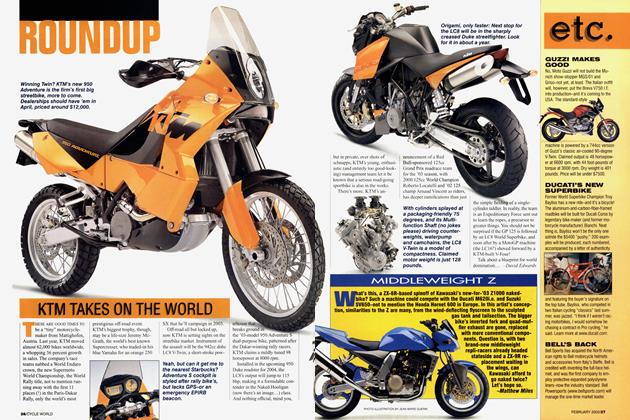

RoundupKtm Takes On the World

February 2003 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupMiddleweight Z

February 2003 By Matthew Miles