Asking the teachers

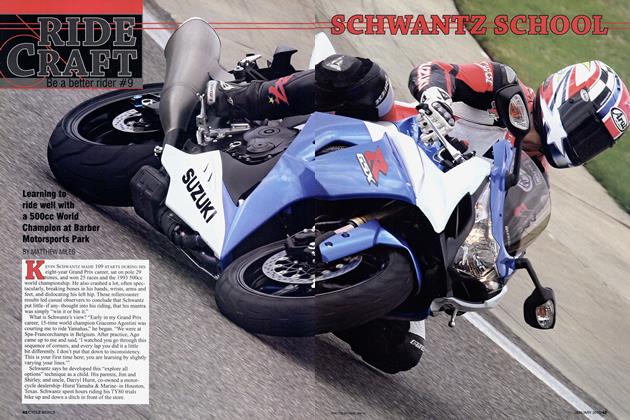

Ride Craft

Experts focus on the human side of the motorcycle performance equation

First in a Series

NICK IENATSCH

WHAT A DIFFERENCE 20 years makes! The best bikes of 1983, when seen with the CAD/CAM clarity of 2003, appear severely limited. And they were. Limited in lean angle, in stopping ability and in chassis rigidity. Ride the Eighties bikes hard and those limits would warn you of impending disaster with wobbles, dragging parts and fading brakes, the mechanical equivalent of a tap on the shoulder and the admonition, “Any more and you’ll crash.”

Fast forward two decades. Throw a leg over a new sportbike or sport-standard and tell us what’s functionally wrong with it. Performance limits are tough to find from either side of pit wall. Let’s face it, the weakest link in the performance of modern motorcycles is the rider. So Cycle World has taken direct aim at that lacking link with this, the first in a series of ridingtechnique stories. Welcome to “RideCraft.”

This evolution of the rider can happen at all levels, something not lost on Valentino Rossi or Colin Edwards. Despite their world championships, they roll their bikes onto the track to practice their craft at every opportunity. From the first practice of the weekend to the final lap of Sunday’s morning warm-up, Rossi and Edwards work on their riding. You may never go racing, but take this work ethic with you in regard to rider improvement-and remember, mistakes made in a street environment are often more painful than mistakes made on the racetrack, where traffic is one-way and an ambulance is mere seconds away. Better skills and judgment help everyone from the commuter to the touring rider to the club roadracer.

Riding enjoyment soars as skills increase, and America’s professional motorcycle instructors agree. They’ve seen the increased confidence of a rider able to control the speed and direction of a motorcycle. We went to several leading schools to ask the bosses the biggest problem they see in their classes.

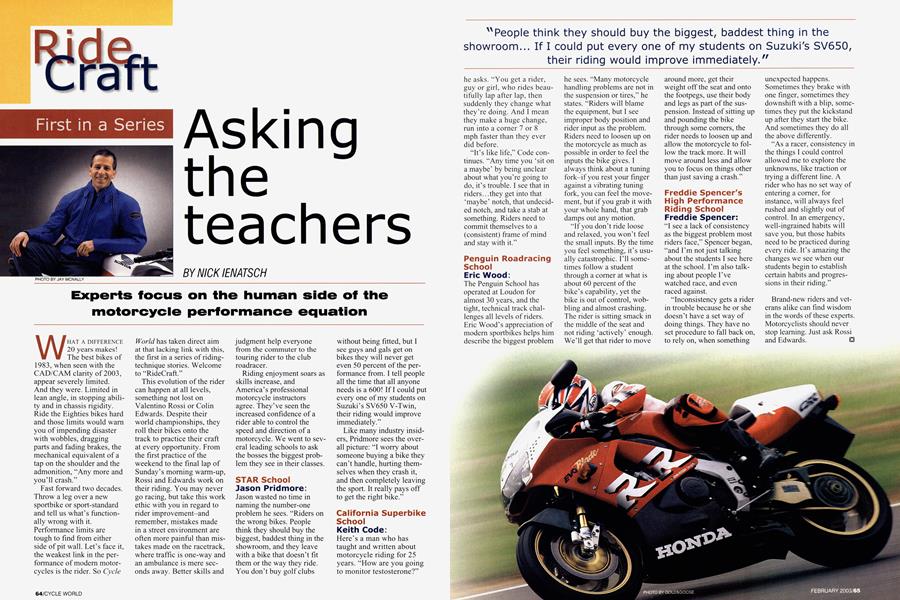

STAR School Jason Pridmore:

Jason wasted no time in naming the number-one problem he sees. “Riders on the wrong bikes. People think they should buy the biggest, baddest thing in the showroom, and they leave with a bike that doesn’t fit them or the way they ride. You don’t buy golf clubs without being fitted, but I see guys and gals get on bikes they will never get even 50 percent of the performance from. I tell people all the time that all anyone needs is a 600! If I could put every one of my students on Suzuki’s SV650 V-Twin, their riding would improve immediately.”

Like many industry insiders, Pridmore sees the overall picture: “I worry about someone buying a bike they can’t handle, hurting themselves when they crash it, and then completely leaving the sport. It really pays off to get the right bike.”

California Superbike School Keith Code:

Here’s a man who has taught and written about motorcycle riding for 25 years. “How are you going to monitor testosterone?” he asks. “You get a rider, guy or girl, who rides beautifully lap after lap, then suddenly they change what they’re doing. And I mean they make a huge change, run into a corner 7 or 8 mph faster than they ever did before.

"People think they should buy the biggest, baddest thing in the showroom... If I could put every one of my students on Suzuki's SV650, their riding would improve immediately."

“It’s like life,” Code continues. “Any time you ‘sit on a maybe’ by being unclear about what you’re going to do, it’s trouble. I see that in riders.. .they get into that ‘maybe’ notch, that undecided notch, and take a stab at something. Riders need to commit themselves to a (consistent) frame of mind and stay with it.”

Penguin Roadracing School Eric Wood:

The Penguin School has operated at Loudon for almost 30 years, and the tight, technical track challenges all levels of riders. Eric Wood’s appreciation of modem sportbikes helps him describe the biggest problem

he sees. “Many motorcycle handling problems are not in the suspension or tires,” he states. “Riders will blame the equipment, but 1 see improper body position and rider input as the problem. Riders need to loosen up on the motorcycle as much as possible in order to feel the inputs the bike gives. I always think about a tuning fork-if you rest your finger against a vibrating tuning fork, you can feel the movement, but if you grab it with your whole hand, that grab damps out any motion.

“If you don’t ride loose and relaxed, you won’t feel the small inputs. By the time you feel something, it’s usually catastrophic. I’ll sometimes follow a student through a comer at what is about 60 percent of the bike’s capability, yet the bike is out of control, wobbling and almost crashing. The rider is sitting smack in the middle of the seat and not riding ‘actively’ enough. We’ll get that rider to move

around more, get their weight off the seat and onto the footpegs, use their body and legs as part of the suspension. Instead of sitting up and pounding the bike through some comers, the rider needs to loosen up and allow the motorcycle to follow the track more. It will move around less and allow you to focus on things other than just saving a crash.”

Freddie Spencer's High Performance Riding School Freddie Spencer:

“I see a lack of consistency as the biggest problem most riders face,” Spencer began, “and I’m not just talking about the students I see here at the school. I’m also talking about people I’ve watched race, and even raced against.

“Inconsistency gets a rider in trouble because he or she doesn’t have a set way of doing things. They have no set procedure to fall back on, to rely on, when something

unexpected happens. Sometimes they brake with one finger, sometimes they downshift with a blip, sometimes they put the kickstand up after they start the bike. And sometimes they do all the above differently.

“As a racer, consistency in the things I could control allowed me to explore the unknowns, like traction or trying a different line. A rider who has no set way of entering a comer, for instance, will always feel rushed and slightly out of control. In an emergency, well-ingrained habits will save you, but those habits need to be practiced during every ride. It’s amazing the changes we see when our students begin to establish certain habits and progressions in their riding.”

Brand-new riders and veterans alike can find wisdom in the words of these experts. Motorcyclists should never stop learning. Just ask Rossi and Edwards.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

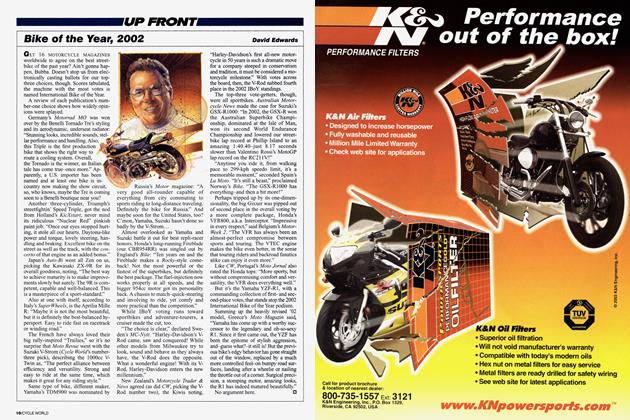

Up FrontBike of the Year, 2002

February 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThem Ice Cold Blues

February 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCSpring Fever

February 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2003 -

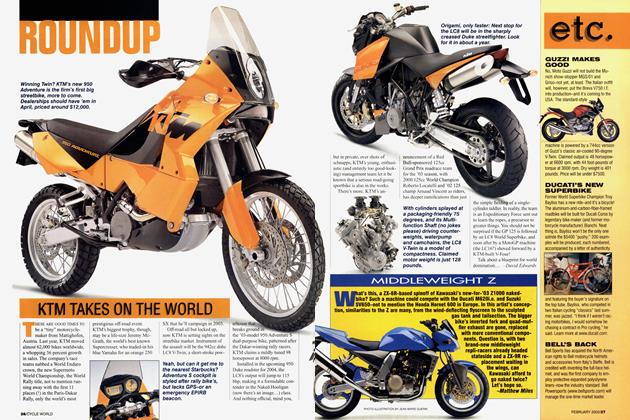

Roundup

RoundupKtm Takes On the World

February 2003 By David Edwards -

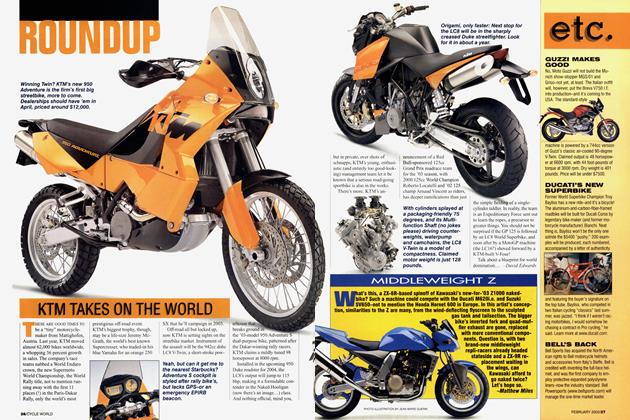

Roundup

RoundupMiddleweight Z

February 2003 By Matthew Miles