Battery Life

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

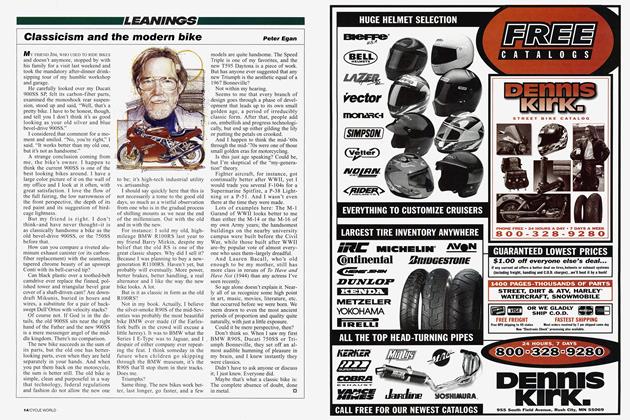

NOT TOO LONG AGO, A READER SENT ME some photos of his sizeable motorcycle collection, all arranged row-upon-row in a beautiful new garage. He had a lot of nice bikes, including quite a few of my all-time favorites, such as a black-andgold Ducati 900SS, circa 1980, and a perfectly restored ’67 Triumph TR6-C.

My favorite photo, however, was not of the bikes.

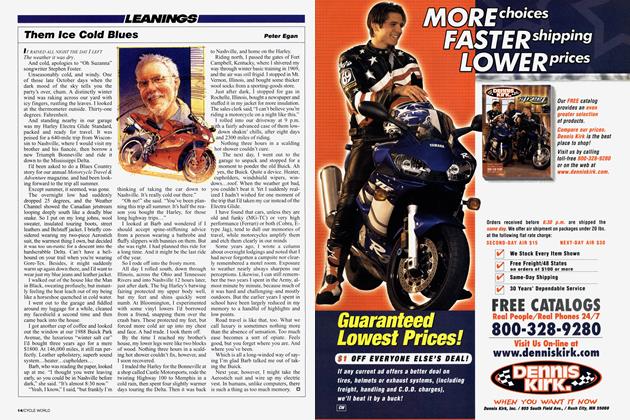

Emblematic of bike collections everywhere was a snapshot of a tall metal storage shelf filled with motorcycle batteries. Tall ones, short ones, long ones. Mixed in with this stunning industrial display of lead and acid were half a dozen Battery Tenders with their various lights glowing green or red, all draped with more wires and hoses and alligator clips than an Intensive Care Unit in a cardiac ward. You could almost smell the sulfuric acid fumes and hear the soft, gurgling percolation of gas bubbles.

I stared at that picture for a few minutes and wondered if I should have it silk-screened onto a T-shirt with the subtitle, “Winter Riding in Wisconsin.” Those batteries, more than any other image I could think of, represented the glowing embers of enthusiasm, waiting to flare up again in spring. Passion on the trickle-charger, as it were.

This photo also reminded me that my own bikes had been sitting for a while, so I repaired to my posh, heated workshop to do the annual Battery Thing where I take them all out, clean off the white powdery stuff, sand the terminals, burn acid holes in my favorite pair of blue jeans and trickle-charge everything on my battery bench.

Yes, I too have a dedicated spot for the handling of batteries. It’s a Sears metal workbench with plywood bolted to the top. It’s way over in the Toxic Corner of my garage, next to the parts-cleaner, as far as possible from any painted surface.

I am a great respecter of the corrosive properties of sulfuric acid. When I was a car mechanic in the Seventies, a guy walking through our shop accidentally tripped on some battery-charger wires, throwing a spark that blew the top off the battery in a BMW 2002 that was parked in the bay next to mine. Blammo! I saw it happening and turned away just in time to miss a face-full of acid.

We doused everything with water immediately, but the car was ruined. So was my shirt. Nasty stuff, acid.

Anyway, I was overdue for a little winter battery maintenance, and in preparation for my long-postponed, much-ballyhooed but virtually imminent dual-sport ride in Baja, I went out to the garage the other night to change the oil in my Suzuki DR-Z400S. But first a little warm-up.

It being winter, I cracked open the garage door, aimed the exhaust pipe into the great frozen outdoors, set the choke, turned the key and hit the starter button.

Nothing.

As in nil. Not a whimper from the starter motor, nor even a sign of life in the LED instrument cluster. Weird. Only a month earlier, I’d taken a short ride during a break in the weather and the engine had cranked like a house afire, but now the battery was dead.

So I pulled off the left sidepanel and removed the long, narrow “maintenancefree” battery, which lives on a little shelf under the seat. I hooked up my 1 -amp Battery Tender for an overnight slow-drip power transfusion. But no lights came on in the charger. Odd. Perhaps the battery needed a bigger jolt to get going. But I hooked up my 2-amp and 6-amp units, successively (yes, to paraphrase the New Testament, my house has many chargers) and nothing happened with those, either. No bounce of the needle, no hum of the charger. Nothing. I might as well have hooked the battery clips to a chunk of 2x4. This little beauty was dead, and not about to be revived. Have to get a new one.

Next I turned my attention to my nearly new but dormant Aprilia RS250 track bike. I turned the key and there was not a hint of life in the LED instrument pod. So I took its tiny battery out (same as the nearby Honda Spree’s) and tried to charge it, with identical results. Another non-conductive block of wood. Have to get a new one.

Moving down the row, my Ducati 900SS and old BMW R100RS both had enough juice to light their headlights, but not quite enough to turn their engines ver more than once. Those batteries came out and took their places on the charging bench, soon gurgling happily back to health.

The Harley cranked and started right up (but should probably get a trickle charge), and I didn’t even try the old 1968 Triumph Trophy 500. That bike’s little gel-cell has been dead for

two years, but the bike always starts first kick in the spring and the lights work fine.

Odd that the only bike I have that starts and runs predictably is equipped with a kickstarter, a dead $12 battery and 35year-old Lucas electrics. So much for our brave new technology.

But then I have felt for many years that the motorcycle battery-even in its most modern form-is an odd throwback to some earlier era, the one piece of equipment that has really improved not at all since I bought my first bike in 1963. And I continue to be amazed that any manufacturer would bury a battery deep in the bodywork of a bike where it cannot be immediately reached.

Battery failure is the third certainty in the world, right after death and taxes.

It can be just as expensive as taxes, too. That little black short-lived maintenancefree unit on the DR-Z cost me $ 126 at the dealer. After ordering one yesterday, I am still bleeding from the ear. The Aprilia battery, on the other hand, was only $18, so maybe that evens things out.

My little bike collection right now, at seven motorcycles, is slightly beyond my normal, self-imposed limit of five, and I’ve been thinking of selling a couple of them to simplify my life and make a little more room in the garage. When I explain this plan to people, I tell them I have too many bikes.

But, in my own mind, I never really have too many bikes. There is no such thing. I just have too many batteries. □