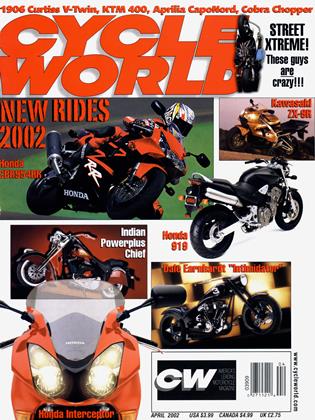

STREETBIKE EXTREME

RACE WATCH

Outlaw stunt riders gain mainstream recognition. The question is, do they want it?

MIKE SEATE

WHACKED-OUT PSYCHOS WITH A DEATH WISH? Or two-wheeled gymnasts forging new ground in an evolving dance between man and machine? Either way, pavement-based sportbike stunt riders are making a mark on motorcycling and, slowly but spectacularly, creeping into the mainstream.

The seemingly endless variations of wheelies and stoppies practiced by these artisans of balance and horsepower were once reserved only for remote stretches of road or loosely organized gatherings wherever motorcycle people congregat-

ed-from the local burger joint to Daytona Bike Week. Thanks to motorsports promoter Cliff Nobles, who formed the Xtreme Sport Bike Association (XSBA) last summer, this new sport took its first step toward legitimacy.

Nobles-the older brother and manager of veteran roadracer Tripp Nobles-was a longtime of the usually illegal sport of street extreme riding, who saw potential where many others have only seen flashing red lights.

“I’d attended too many races where kids were putting on stunt shows out in front of the circuits in the streets. Some of them were getting arrested, so 1 thought, ‘Why don’t we just invite them inside?”’ Nobles said.

Naturally, there were obstacles to having the roadracing community open its doors to these amateur street stunt riders. First, there was the issue of whether racing fans were even interested in watching riders skate behind their motorcycles, raise hell and generally mock conventions of safety. Though amateur stunt videos, often shot in traffic on shoestring budgets, sell thousands of copies for groups like Ohio’s Starboyz and established stars including Brazilian stunt sensation A.C. Farias, stunt riding maintains an outlaw image that many motorcyclists want little to do with.

Nobles also noted that many stunt teams are committed to the thrills and bad-boy image that stunting on public roads provides-racetracks, they’ll tell you, are for squids.

Undeterred, Nobles lobbied organizers to allow a pair of hour-long stunt exhibitions during the CCS/Formula USA Races at Pennsylvania’s Pocono International Raceway in August, 2001. As a relative outsider to the street stunt community, Nobles was uncertain whether these fiercely independent riders would respond to his offer to play by the rules, but the initial turnout was encouraging.

The weekend’s “Scene One’’ event saw 13 riders representing five well-established stunt teams in competition. They plied the roadracing crowd of some 14,000 with the gravity-defying moves that have filled untold amateur videos-and police dockets.

Regardless of whether you believe stunt riders should be carted off to the nearest jail or lauded as heroes, it was tough to deny the level of talent on display. Among the notable moments was a series of 90-mph backwards seat stands by Driving To Endanger’s Chris MacNeil on a Honda CBR900RR and a truly demented series of stoppies (or endoes) by Cory Kufhal of Wisconsin’s D-Aces, riding a Suzuki TL1000S Twin. Mostly made up of twentysomething street riders who are driven by dreams of instant fame (and plenty of adrenaline), the XSBA show proved popular with Pocono’s crowds, even though the repertoire of stunts wore a little thin at times.

For the XSBA’s part, they actually managed to organize the riders into something resembling a professional competition: Full leathers and helmets were mandatory, and a panel of judges from roadracing teams and stunt-video production houses chose winners at the end of the two-day event.

Slick and well-choreographed moves from Pauly Sherer, a part-time roadracer and founding member of Las Vegas Extremes, took first place and a check for $1100. Sherer, like hundreds of other streetbike outlaws, was inspired by Showtime, a slickly produced videotape by British stunt rider Gary Rothwell. The long, level roads of Nevada played a major role in the formation of Sherer’s group, said founding Las Vegas Extremes member Derrick “D-Mann” Daigle.

“Modern sportbikes may be engineered for incredible cornering speeds, but out in the deserts, there just aren’t that many corners where you can get your knee down. We started stunt riding just out of boredom,” said Daigle, 31, a fire-truck driver who today rides with Tampa, Florida’s Team X-Treem.

Similar stories spring up when the hows and whys of the street stunt movement are explored. Youthful ennui, an abundance of horsepower and Midwestern highways as dull and featureless as a politician’s wardrobe provided a perfect incubator for stunt riding.

For example in Cleveland, where Starboy Kevin Marino says stunt riding was a way to help poor, working-class kids get noticed: “Roadracing is too expensive and has too many rules. I was a scrub at basketball.

But I can outride anybody on a motorcycle,” said Marino, 30.

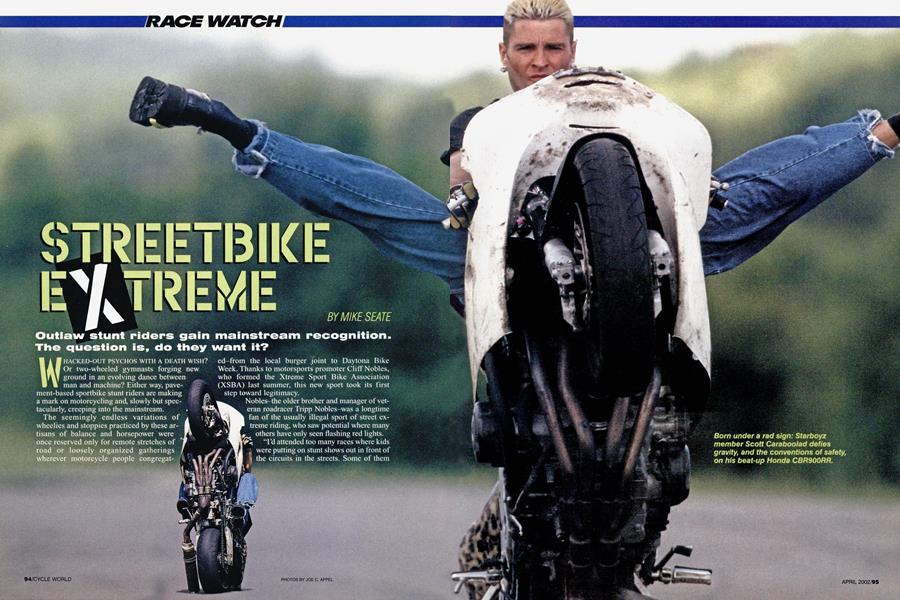

The Starboyz are as recognizable for their trio of fur-covered Honda CBR900RRs as they are for amassing traffic citations. Marino, who covers the bikes in fur to deflect crash damage, never intended to make a career out of stunt riding. The Starboyz only began recording their street antics for kicks, using the tapes to wow friends at parties and local bike shops. Crowds often gathered as the tapes played, and soon, calls were flooding in for hundreds, and then thousands more.

But the calls weren’t all offering praise. Detractors who maintain that street stunt riding reflects badly on the sport of motorcycling often phone the police at the first sign of a smoking rear tire.

That’s what AMA Marketing Vice President Gary Sweet did during Daytona Bike Week 2000, when he found himself in traffic behind a group of Starboyz imitators. “I pulled over, took, off my helmet and ealled 911. I was shocked, frankly. What these guys do is the absolute worst thing that can happen to motorcycling,” Sweet said.

Akron, Ohio, police patrolman Sgt. Fred Bietzel couldn't agree more. “No doubt these stunts are fun to do and

watch, but if they have to do it, they should limit it to racetracks. These kids don’t realize how dangerous this is,” he said.

Older, and maybe a little bit wiser, the Starboyz-so named for their matching Vanson Star jackets-seldom practice on the streets and highways, opting instead to trailer their bikes to performances. Last year, they were featured in several of sportbike-crazy England’s top enthusiast magazines, and corporate sponsorships have started flooding in. At Daytona Bike Week 2001, they found that four-time World Superbike Champion Carl Fogarty was among their biggest supporters. With Foggy’s help, the Starboyz have a tour of the British Isles scheduled for this summer.

Financial independence is fine, Starboy Scott Caraboolad says, but he’s careful to maintain his street credibility. To thumb their noses at the corporate backing for Noble’s XSBA event, for example, the ever-mischievous Starboyz staged their own stunt festival at Cleveland’s Thompson Dragway on the same date.

“It’s cool getting paid for doing this in a safe, off-road environment and not getting chased by the cops. But I don’t know if we’re ready to start letting corporate money and old dudes who don’t even ride tell us how we’re supposed to do things,” Caraboolad said.

The success that the Starboyz have enjoyed prompted dozens of imitators, and thus the majority of streetbike stunt videos share a casual disregard for the laws of traffic and gràvity. There are, however, exceptions. Todd Colbert, the lanky, innovative creator of Tampa, Florida’s Team X-Treem, for instance, has long preached the necessity of wearing full leathers and helmets when stunt riding, but he fights an uphill battle.

“They're smart enough to know they can get hurt, but they dress to impress. They’re more worried about looking cool than being safe, and that’s a shame,” said Colbert, 32, who utilizes an airport runway for stunting.

In New York, Joe Lupo of Brooklyn’s Wheelie Boyz says streetbike stunt rid-

ing was an inevitable offshoot of the local drag-racing scene, where the ability to pull a five-block-long wheelie is as integral to keepin’ it real as muscle shirts, gold chains and a 300watt car stereo.

Lupo may know the street extreme scene intimately, but he offers no deep, existential underpinnings to the movement.

“Kids get bored,” he says with a shrug. “When you’re 20, 25 years old, you think you’re invincible. Sure, it’s dangerous, but let’s face it, kids take on a certain amount of risk just riding a motorcycle. Every time you read a road test of a new sportbike, they’re like, ‘The front wheel comes up easily in the first two gears.’ Some kids read that and they want to know, ‘How high and how long?”’

That curiosity and one-upmanship fuels the script for just about every streetbike extreme video in existence: One rider pulls a stand-up wheelie for a mile, then the next guy one-ups him with the same move, only this time he’s sitting on the gas tank, legs draped over the handlebars. At 110 miles per hour. And on it goes until the palmcorder runs out of batteries or a nearby motorist runs out of patience and calls the police on a cell phone.

The sport’s popularity has also forced riders to take on new risks if they’re to stay ahead of the competition. On his tape Full Leather Jacket, former Universal Studios stuntman J.T. Holt displays something called a Switchback Insane, a sort of tank-mounted headstand performed on a speeding Kawasaki ZX-7R. Daigle and Colbert’s “Ghost Ride” involves two GSX-Rs moving at high speed. Daigle dismounts his leading bike by sliding rearward and jumping off the back and onto the front of Colbert’s. Then, they let the lead bike ghost along a half-mile or so, at which point he jumps back on.

Both of these stunts were filmed on closed courses. What happens when an amateur inevitably copies them on the streets is anybody’s guess.

So, as stunt riders tire of negative publicity and succumb to the lure of performing for prize money, can furcovered sportbikes flying down the back straightaway become the next big thing at roadracing events?

That remains to be seen. Nobles has announced plans for additional XSBA events throughout 2002, while Colbert has launched a competitive series known as the World Stunt Riding Championships, which hopes to attract some of Europe’s top stunt riders to the states.

But taming the wild ones of street extreme is not going to be easy. At Pocono, several of the rowdier stunt teams were ejected from the venue by security. Many of the sport’s bestknown practitioners are still wary of joining forces with the XSBA, which stunt rider Peter Marmorato of New York’s Finest called “people who are trying to turn what we do into family entertainment.” Either way, it looks like motorcycles flying by on one wheel may be on their way into the mainstream.

Mike Seate is a staff writer for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review and recently completed a book, Streetbike Extreme. on the outlaw stunt-riding movement.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter of the Month

April 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Mouse That Roared

April 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Rpm Chronicles

April 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Bmw Über-Tourer Twin

April 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUltimate Towing Machine?

April 2002 By David Edwards