Puppy Love

If it wasn't for the Cucciolo, Ducati might still be making radios

OF WARS, IT'S OFTEN BEEN SAID, THE SURVIVORS sometimes envy the dead. Certainly, there were many Italians who felt that way following World War II. Under the misguided leadership of Mussolini, Italy had sided with Hitler’s Germany, and consequently was bombed into submission.

One of the cities hardest hit by the Allies was Bologna, which in the wake of resident Guglielmo Marconi’s invention of the radio-telegraph had become a hotbed of Italian industry. More to the point of this story, Bologna was home to the Societa Scientifica Radiohrevetti Ducati, which prior to the war had manufactured cameras, radios and one of the earliest electric razors. During the war, Ducati supplied field radios and gun sights to the Axis armies, which made it a prime target for Allied bombing runs. By the time hostilities ceased in 1945, not only had a significant portion of the factory been reduced to rubble, there was no longer a demand for its products. The firm’s 7000 war-weary employees needed something to build.

As fate would have it, a man named Aldo Farinelli, work-

ing for engineering firm Siata in Turin, was at that time developing a product that would change Ducati’s fortunes. Farinelli, realizing that post-war Italy would be starved for low-cost transportation, had developed a simple engine that clipped onto a bicycle frame to create what would one day be known as a moped. Called the Cucciolo (Italian for “puppy”), owing to its barking exhaust note, the air-cooled 48cc four-stroke Single had a low 6.25:1 compression ratio that let it run on anything resembling gasoline, and went more than 200 miles on a gallon-both important considerations in this period of strict fuel rationing.

Siata couldn't produce the engine in large quantities, but Ducati could. So in 1946 the company began to build Cucciolos, selling them for the equivalent of $25 apiece while paying royalties to Farinelli and Siata.

Ducati was in the motorcycle business.

Reports of the total number of Cucciolo engines built by the time production ended a decade later vary widely, but most experts agree that it was between 200,000 and 400,000. Few remain today, most having been ridden into the ground.

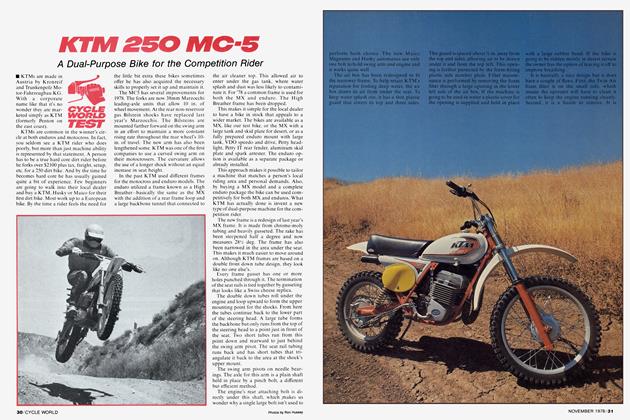

Primitive yet elegant in design, the Cucciolo had its cylinder, head and a portion of the crankcase cast as one piece in lightweight silumin alloy, with its two valves operated via pullrods and external rocker arms, and splash lubrication of the crankshaft. Fitted with a tiny 9mm Weber carburetor feeding a lengthy intake tract, the little engine made impressive torque for its size, especially compared to the primarily two-stroke competition its success spawned. And it rarely fouled sparkplugs or seized.

Starting was moped-style, by pedaling, and the early twospeed transmissions eventually gave way to three-speeds, operated via the buyer’s choice of pedals, twistgrip or automotive-style hand lever.

The Cucciolo’s basic layout was refined over the ensuing years, displacement growing from the original 50cc through 55 and 60 to an eventual 65cc. Initially, output was a single horsepower at 4500 rpm, though this figure rose to 2.25 bhp on the later “Type 3” versions. Top speed rose accordingly, from 30ish mph to 45 mph.

The Cucciolo’s speediness was validated by one Ugo Tamarozzi, who in 1951 won a bronze medal at the International Six Day Trial held in Italy, then set numerous 50cc world speed records at Monza, best of which was a flying kilometer at 48 mph.

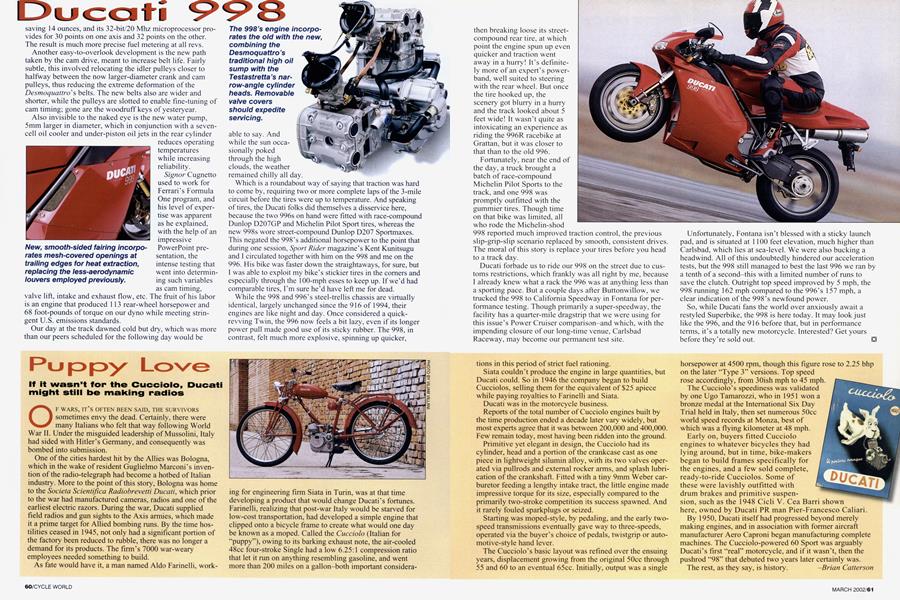

Early on, buyers fitted Cucciolo engines to whatever bicycles they had lying around, but in time, bike-makers began to build frames specifically for the engines, and a few sold complete, ready-to-ride Cucciolos. Some of these were lavishly outfitted with drum brakes and primitive suspension, such as the 1948 Cicli V. Cea Barri shown here, owned by Ducati PR man Pier-Francesco Caliari.

By 1950, Ducati itself had progressed beyond merely making engines, and in association with former aircraft manufacturer Aero Caproni began manufacturing complete machines. The Cucciolo-powered 60 Sport was arguably Ducati’s first “real” motorcycle, and if it wasn't, then the pushrod “98” that debuted two years later certainly was.

The rest, as they say, is history. Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCollecting Made Easy

March 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe 11th-Hour St1100

March 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCKnock, Knock...

March 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

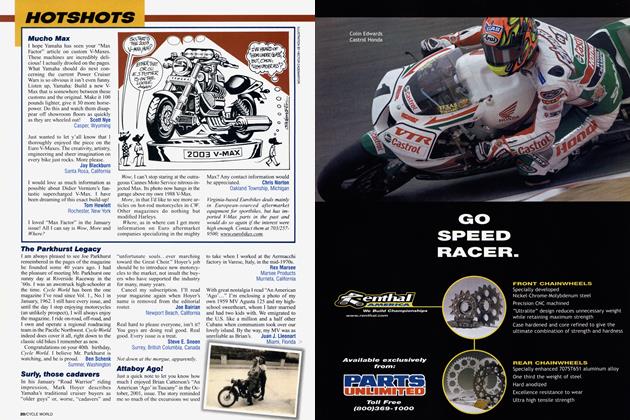

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupMotogp's Newest Recruits

March 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHonest Injun?

March 2002 By David Edwards