Beginner's Luck

UP FRONT

David Edwards

QUESTION: WHAT DO A JAUNTY LITTLE Honda Mini-Trail 50 and a booming works BMW rally bike, a scruffy Kawasaki EX500 club racer and Wayne Rainey’s fearsome YZR500 Grand Prix bike, a used Honda CB175 and a just-minted $60,000 oval-piston Honda NR750 all have in common? Answer: Me.

No, today’s topic is not Mister Dave’s Amazing Scrapbook of Rides. Rather, it’s about the proper way of learning how to ride a motorcycle, something that, sadly, more and more people bypassing.

Simply put, here’s the secret to a safe, successful, extended timespan behind the handlebars: Start small and work your way up. Violate that mandate at your own risk.

My own path from knee-high tiddlers to today’s rocketship roadbikes started with a succession of 50s, 90s and 125s in the dirt, then progressed to that CB175 streetbike, which in turn was traded for a CB350. Some 30,000 miles later, I moved up to my first big bike, a 1977 Yamaha XS750 Triple. I was 22 at the time and also had three years of amateur motocross in my logbook, racing a Honda CR125 and Suzuki RM 125 in the Novice and Intermediate classes. Yet the first time I goosed the big Yamaha to redline through the first three gears, I seriously contemplated what I’d gotten myself into. I wasn’t accustomed to the effortless, abundant amount of speed available.

Of course, my old XS750, a powerhouse in its day, an “expert’s bike,” seems a little lame compared to even today’s 600cc sportbikes, machines with more sheer acceleration and top-end than the liter-class hot-rods of my youth. Beginners’ bikes? No way-nor are they marketed as such-but teenage testosterone has a way of overcoming relatively high purchase prices and even more prohibitive insurance premiums. Some firsttime riders are wrongly climbing aboard 600s-or, shudder, 1000s-and bumbling their way along a learning curve that can be precipitously steep.

Recently, I received a letter from a man caught in the kind of deep, dark despair for which there is no condolence, except perhaps for the inexorable passing of time. His 19-year-old son, full of life, with many friends and a bright future, had just been killed in a motorcycle accident.

The son, an inexperienced rider aboard a lOOOcc repli-racer, was out for a little backroad cut-and-thrust with a couple of buddies. Approaching a downhill curve posted at 35 mph, the son swung out to pass his pals at about 50 mph. According to witnesses, he suddenly straightened the bike up and dynamited the front brakes. The tail of the bike lifted up and he went over the handlebars while the bike cartwheeled off the road. Cause of death, noted the coroner’s office, was “blunt force trauma to the head.” The son had been wearing a full-face helmet, but it could not protect against a broken neck.

In his grief, the father lashed out at motorcycling, at bike-makers, at magazines.

“Why do manufacturers sell 150horsepower bikes to new riders? Why aren’t anti-lock brakes standard equipment? Why do magazines promote fast riding and crazy stunts? My son is dead. Nothing can bring him back. If he had never ridden a bike, he would still be alive today...”

Then was not the time to respond to the father; besides, nothing I could say would assuage his pain. But the simple fact is that high speed did not kill his son-the accident happened at a moderate 50 mph, in a corner that most likely could have been taken at 75, no sweat. Nor was horsepower the culprint; statistics show big-bhp sportbikes are actually under-represented in crash data. Nor the lack of ABS-in fact, I’d argue that locking the front brakes and low-siding the bike in this case might have cost a collarbone but saved a life.

What happened here, tragically, is that inexperience and youthful exuberance caught up with the son at exactly the wrong time. His skills were simply not up to the task.

If there’s any good news in this, it’s that it does not happen all that often. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the year 2000 there were 219 teenage deaths in streetbike accidents. This compared to approximately 8000 teenage auto fatalities. Fact is that motorcycles-many parents’ worst fear-just don’t rate as a leading cause of death. The Center for Disease Control, which tracks such things, has statistics that show among those in the under-25 age group, about 5000 will be victims of homicide. Suicides account for another 4000 deaths per year. Cancer and heart disease take some 3000. Motorcycles are not even a blip on the CDC’s radar screen. And the bike figure would be even lower if young riders used a little common sense^J9 percent of those killed were not wearing helmets, 28 percent were without the proper license and 21 percent were intoxicated (there is considerable overlap here, with hopped-up, lidless, unlicensed riders all but asking to be a statistic).

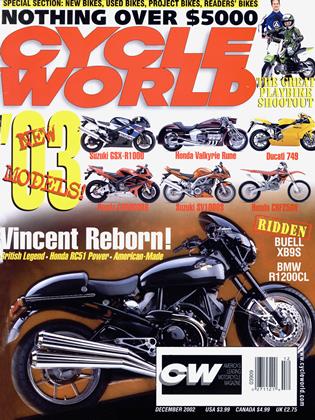

None of this, I know, is of much solace to a father mourning the loss of his son. Also, to this audience-the average CW subscriber is in his late 30s/early 40s, with 23 years’ riding experience and 2.3 bikes in the garage-it’s a bit like preaching to the choir. But all of us have friends, co-workers and relatives with sons (and in increasing numbers, daughters) just hankering to ride motorcycles. If they’re under 16, show ’em this month’s Playbike Shootout story. Every really good street rider I know has considerable dirtbike experience, and this year’s crop of trailbikes is truly outstanding. No better family fun.

If the kids are of legal age and want a roadbike, have a look at this issue’s “Cheap Thrills” comparo. Great learner’s bikes in sport, standard and cruiser styles, all for about $100 per month, warranty included. Just add instruction.

Sometimes you make your own Beginner’s Luck. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue