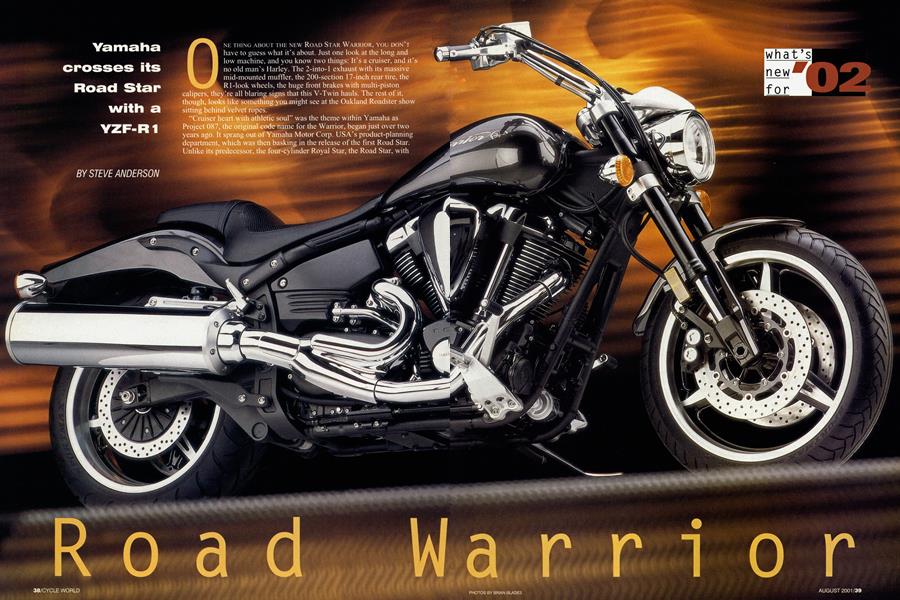

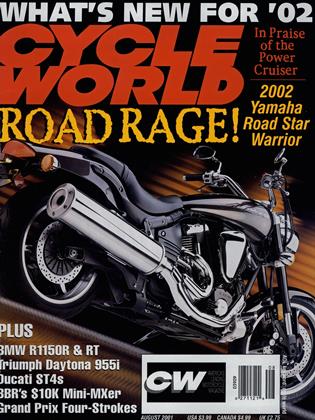

Road warrior

Yamaha crosses its Road Star with a YZF-R1

STEVE ANDERSON

ONE THING ABOUT THE NEW ROAD STAR WARRIOR, YOU DON’T have to guess what it's about. Just one look at the long and low machine, and you know two things: It’s a cruiser, and it’s no old man's Harley. The 2-into-l exhaust with its massive mid-mounted muffler, the 200-section 17-inch rear tire, the R1-look wheels, the huge front brakes with multi-piston calipers, they’re all blaring signs that this V-Twin hauls. The rest of it, though, looks like something you might see at the Oakland Roadster show sitting behind velvet ropes.

“Cruiser heart with athletic soul” was the theme within Yamaha as Project 087, the original code name for the Warrior, began just over two years ago. It sprang out of Yamaha Motor Corp. USA’s product-planning department, which was then basking in the release of the first Road Star. Unlike its predecessor, the four-cylinder Royal Star, the Road Star, with its big, air-cooled pushrod V-Twin, was going to be a winner, with strong, positive feedback from dealers at its introduction. But where to go next?

what's new for '02

The product-planning group (consisting of Ed Burke, Derek Brooks and Macky Makino) had been spending a lot of time at U.S. motorcycle rallies and talking with cruiser customers, “Trying to determine,” says Brooks, “what grabs your heart on a motorcycle.” All the hot-rod customs they saw, all the Harley clones from small builders, even the huge Harley performance aftermarket was sending them the same message: that there was a strong desire out in motorcycle land for performance cruisers. But it had to be the right performance cruiser.

“We didn’t want to do another U.J.C. (Universal Japanese Cruiser),” says Brooks. Working within a traditional American (Harley/Indian) engine configuration-narrow-angle, long-stroke, pushrod, air-cooled V-Twin-was what defined the Road Star as different from all of its Japanese compatriots. “The engine styling was as important as the way the rest of the bike looked,” says Brooks. “And we already had the V-Max as the highest performance cruiser,” notes Makino. For Project 087, the important thing would be not to attempt to build a V-Twin that would outdo the V-Max, but to instead preserve the traditional configuration of the Road Star while injecting it with excitement, in both performance and appearance.

But first, Yamaha Japan had to be convinced. “In our very first discussion with the engineers,” says Brooks,

“they asked, ‘Can we do liquid-cooling and overhead cam?’ And we said, ‘No way!’ Rather than make it something else, we wanted it in the Road Star family.” When the engineers finally believed that these Americans were serious, they began looking for other ways to boost performance. Some of that would come from reworking the Road Star engine, from a displacement increase and a thorough re-tuning, but a big boost would come from the best possible source-keeping the weight down.

The engineers threw a challenge right back to the planners: If we can’t do an all-new engine, can we at least do an aluminum frame? Brooks said he had pictures of a Deltabox dancing in his head, and was ready to tell them no. But the engineering team was adamant: Meeting performance goals required keeping weight down, and the aluminum frame was essential. Besides, they didn’t have anything like a twin-beam sportbike frame in mind. So early in the project, the Warrior acquired its single most unusual feature, an aluminum chassis that looks like that of a conventional cruiser, but isn’t. Weighing just 38.6 pounds, 19 less than the steel frame of a standard Road Star, the multiple castings and tubes of the Warrior’s frame tie its axles together 40 percent more stiffly. And the TIG-weld joints in the aluminum structure look far cleaner than those of any but a custom shop’s steel frame.

The Warrior began to take shape. Its original design had been hinted at by Yamaha’s GK Design studio in California, but now with engineering involved, real issues of function came up against appearance. For power, the Road Star’s single side-mounted carburetor wouldn’t cut it; instead, the Warrior would get better-flowing downdraft cylinder heads fed by two 40mm throttle bodies and fuel-injection. That meant some gas tank space would be consumed by airbox. And as with all big Twins that want to make real power, a sizable airbox would be required if it weren’t to be absurdly restrictive. Compromises were made. The gas tank would have a large hollow underneath to house part of the airbox, and some of the airbox would sneak out the side of the tank and tuck down the right side of the engine, maintaining the visual tradition of the Harley and standard Road Star sidemounted air-filters. To pack four gallons of gas without ballooning the gas tank absurdly, some fuel would be carried in a sub-tank underneath the seat. To make room for that, the Warrior’s single shock would tuck under the engine. Unlike the tension-shock design of a Buell, a linkage would compress the Warrior’s shock conventionally when the rear wheel hit a bump.

Meanwhile, styling responsibility for the production Warrior had shifted to Japan, but the Americans remained intensely involved.

Members of the U.S. product-planning staff made monthly trips to Japan to ensure that the initial direction they had given the Warrior didn’t get turned on its way to a finished motorcycle. The look, as previously mentioned, is long and low, immensely aided in that front-to-back flow by the absence of rear shocks to break the lines. The gas tank is reminiscent of the stretched banana shapes seen on any number of highly customized Harleys.

And everywhere on the bike, performance touches blend with American custom styling for pure hot-rod appeal.

Many of those hot-rod elements come straight from Yamaha’s ultra-sportbike, the YZF-R1. The upside-down fork, the wheels, the front brakes, are all lightly altered versions of R1 components. Likewise, the aluminum swingarm of the Warrior owes more to sportbike designs than those of other cruisers. The big rear disc brake and caliper come from the FJR1300 sport-tourer. Other parts, such as the exhaust system, are all new, but blend sportbike and cruiser esthetics. The huge muffler is essential for power, and the Yamaha stylists didn’t try to hide it; instead, they made it look like a big can-muffler from a supersport bike.

Of course, this performance look begs the question: Will this air-cooled, pushrod machine perform? The engineers did their best, keeping dry weight down to just over 600 pounds, boosting displacement through a 2mm overbore to 1675cc (from 1602cc), and changing almost every component in the top-end of the Road Star engine. Their goal was a 40 percent increase in power from the Road Star, and a 10 percent increase in torque-figure 75 rear-wheel bhp and a stout 95 ft.-lbs. While we saw preliminary power curves for the Warrior, final road certification work continues as this is written, and Yamaha can’t say for sure that the machine will meet its goals. But if it does, Yamaha will have achieved something interesting: It will have matched the power-toweight ratio of the Honda VTX1800 with a far more wieldly, simpler cruiser. If so, expect to see the Warrior tum a low 12second quarter-mile, very similar to that of the Honda, and perhaps score even slightly better in roll-ons.

But where Yamaha hopes for the Warrior to really shine isn’t just in acceleration, but in allaround performance. Its radial tires are a clue here, as is the height at which the muffler is mounted: This cruiser was meant to lean. Even a casual glance down the sides of the Warrior tells that it has been given more cornering clearance than almost any other big-Twin cruiser, and the high-quality suspension components, sticky tires and stiff frame promise to let it make use of every bit of it.

All the same, the Warrior sticks to many of its cruiser roots. All fenders, fuel tanks and major covers are steel, making for easier custom painting. In the same spirit, the final drive, like that of the Road Star, is via belt. Why? A belt is lighter and simpler than a shaft, requires only minimally more maintenance, and makes the fitment of custom wheels a real possibility. Any aftermarket company turning out cool billet CNC wheels for Harleys will find it trivial to alter its designs to bolt up to the Yamaha. Likewise, the Warrior’s riding position is similar to that of a number of newer Harley models such as the Softail Deuce, with forward footpegs but a handlebar that keeps you sitting fairly erect. Perhaps the only compromise in traditional cruiser virtues is in the passenger accommodations; that high muffler has meant high rear footpegs, resulting in less legroom than on other big-inch Twins.

Of course, offsetting that are some of those little details that tend to grab the attention of every motorcyclist who sees the Warrior. Take the blue instrument lights, for instance, or the cool mix of LCD and conventional analog displays in the tach and speedometer. Or the skinny, ultra-light and near ever-lasting rear LED brake and taillight. Brooks is particularly proud of how the Warrior has begun to break away from the Japanese tendency to chrome any surface of a cruiser that isn’t painted; he likes to point out the interplay of texture and surface finish on some of the engine covers and fender brackets, detailing that helps give the Warrior a real American hot-rod mechanical feel.

Of course, what Yamaha is really offering with the Road Star Warrior is yet another definition for motorcyclists to vote on in answering: What really makes a cruiser? It, the Honda VTX1800 and Harley’s soon-to-be-released liquid-cooled power cruiser are all offering alternative visions of how performance should meet American custom style. Harley, with the luxury of thoroughly dominating the big-inch cruiser market with its current Twin Cam, intends to take a very different, high-revving approach to achieve performance with its VRinspired machine. Honda is taking the King Kong route, attempting to smash everything in the VTX’s path with size and technology in what is otherwise a very conventional iteration of its Shadow family. Meanwhile, just possibly, the Warrior, by staying within conventional cruiser engine constraints while embracing sportbike chassis components, may end up being the truest American hot-rod of all. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue