Spring in Spain Ducati Style

Riding the 996R, MH900e and Monster S4, when not eating paella with sea creatures

PETER EGAN

ON THE IBERIA AIRLINES FLIGHT TO SPAIN, I WAS sitting in a coach-class seat with my lanky frame compressed into the folded mousetrap position, reading a magazine article about Basque separatists and their terrorist bombing campaigns.

I put the magazine down for a moment and thought to myself, “Why don’t international terrorists ever do anything useful, like kidnap the CEOs of all the major airlines and make them ride in their own coach-class seats for 9 hours?”

An evil thought, but one that was soon mitigated by the sight of a warm sun rising over the mountains of southeastern Spain. From the air, it looked like Southern California, only more of it, with fewer people. California in the Fifties. To a guy who’d just left his car in a windswept arctic parking lot at a Wisconsin airport, those twisting, snowless roads below looked pretty good.

Spain should probably have its own Statue of Liberty now, perhaps in Valencia Harbor, with the inscription, “Bring us your cold, your sodden, your snow-drifted, sleetdriven huddled masses of motorcyclists.” If they don’t already.

In recent years, Spain has become like the Florida or Southern California of Europe, a land where bikes may be tested, raced and ridden on warm, dry pavement when all else is locked in deep chill. The place has a lot going for it.

The new Testastretta motor is freer-breathing, quickerrevving and more muscular everywhere than my old 996."

Post-Franco prosperity (yes, he’s still dead), a public mad about bikes and a host of excellent racetracks have made it the place for European magazines and most race teams to do their winter testing.

Even Italy is colder-and having one of its worst winters in recent history-so Ducati chose to introduce its new 996R at the Ricardo Tormo track in Valencia, while holding out the added carrot of an all-day street ride into the mountains on the long-awaited Mike Hailwood-inspired MH900e and the 916-powered Monster S4. Our week would end with tickets to the World Superbike opener at Ricardo Tormo. When Editor Edwards interrupted my snow-blowing (Jacobsen Hydro 1200 Super Chief with two-stage blower) to offer me this trip, I was taken aback. “Me? Track-test the new 996R? Isn’t this a job for Don Canet, or someone else who’s fast? I’ve only ridden on a racetrack four times in the last 20 years. Also, I just turned 53...”

“You’ll do fine,” David said. “You actually owned a 996, and I seem to remember a column about a track day on it at Road America a couple of years ago.”

“Okay,” I said. Notice how easily I was convinced.

Ducati’s minivan picked me up at the Valencia airport, along with two other American journalists, Sport Rider's Kent Kunitsugu and Melissa Berkoff from Roadracing World. Suburban Valencia is miles of mostly gleaming new high-rise apartment buildings, but the downtown has considerable Old World charm, with broad avenues, tree-lined promenades like the Ramblas of Barcelona and sidewalk cafes.

There’s also a new downtown section of spectacularly modem architecture in soaring public buildings that look like the Future as it was imagined when I was a kid. Tomorrowland. All they need is personal helicopters dotting the sky. But most of the city looks almost like Paris, with a Mediterranean flavor.

“Lots of palm trees,” Kent observed.

“That’s a good sign,” I said. “Always.”

I could think of no exceptions, save, perhaps, an area north of Saigon. ®

And as in Vietnam, we could hear random explosions around the town. Basque separatists again?

“No,” our driver said. “The festival of Fallas is coming up. It’s a celebration of fire and of spring, and everyone shoots off fireworks. We build big statues and then bum them.” Fire, spring, palm trees. I was liking this place already.

We checked into a hotel in downtown Valencia and that night had a tech presentation and then dinner with the Ducati folks. Valencia’s specialty is paella, a mixture of rice, saffron and seafood baked in huge round pans. Excellent. Many salads and dishes also contain “fruits of the sea,” which are not fruits at all, but small Mesozoic marine creatures with either no eyes or eyeballs on long stalks. Tentacles are popular, too. Luckily, I am fond of such things.

The food in Spain is vastly better than it was 28 years ago

when my wife Barb and I spent a month touring the country in a clapped-out Simca 1000. Hotels are better, too. And the roads. The people are more relaxed, as well. Everything is better. Spain is up to speed with the rest of Europe now, with Franco gone.

In the morning we had our Valencia orange juice, then drove out to the nearby track, a convoluted circuit that sits in a natural amphitheater of hills-a first-class facility with big clean restrooms that even smell good! Posters call the track Un circuito dentro de un Estadio. I thought maybe dentro had something to do with teeth, because the track sits like a filling in a molar. But dentro means “within.” Good thing they don’t have me do their posters.

“A filling in a molar?” It would only confuse people.

Leathered up, we approached a row of a dozen gleaming red 996Rs. That’s 12 of only 500 R-models made. Of those, 150 have been designated for race teams, and the rest were sold over the Internet last fall, for $26,000 apiece. Strange, testing a bike that’s already sold out. Kent and I were given bike number 9, to alternate lapping sessions.

The main changes in the 996R from the standard model are in the engine and brakes. The Testastretta, or “narrow head,” engine cranks out a claimed 135 horsepower at 10,200 rpm,

13 bhp more at 200 rpm less than the previous 996SPS engine. Most of the improved performance comes from head design, the narrower included valve angle (25 degrees vs. 40) allowing a smaller combustion chamber for higher compression and better flame travel so the engine can use a 2mm wider bore and 2.5mm shorter stroke. Intake and exhaust tracts are straighter, too, with a new, single fuel-injector nozzle mounted dead center in either throttle-body bore.

Intake valves are larger as well, and the new-generation engine-control module is dramatically smaller and lighter, like the difference between your grandparents’ French Provincial hi-fi console and a Sony Walkman. Overall, the engine gets new crankcases, crankshaft, pistons and cylinder head covers for easier valve adjustments.

New Brembo four-pot calipers give the pads an extra dose of leading edge, increasing initial bite when the brakes are applied. The calipers themselves are more rigid for better feel through a revised master-cylinder/caliper ratio at the lever. Brake rotors are lighter, as well.

Other than that, the bike looks pretty much like the old 996 (still stunningly beautiful), except for revised hot-air exits in the fairing, for less turbulence and to accommodate a larger radiator. The fairing is now of carbon-fiber, which helps reduce the bike’s weight by a reported 15 pounds.

So does all this make it better on the track?

Yes, it does.

The 996 is a great track bike to begin with; the ergonomics

"The MH900e is functionally a pleasing modern bike, with an overlay of vintage simplicity. Too bad, though, about the riding position."

that make it something of a torture rack on the street make it a delight on the track. It’s small and lean, with just enough weight forward on the wrists to get telepathic messages from the front tire through your palms. But the engine is the big change.

A strong, hard-hitting motor with a broad torque spread has simply been made more so by the new revisions.

It’s freer-breathing, quicker-revving and more muscular everywhere than the engine on my old 996. Below allout racing intensity (i.e., my normal operating range) you can simply short-shift and hammer around the track at anything above 4000 rpm without fear of losing your drive off comers. And a good thing, too.

The Valencia circuit is a tight, very technical course with 13 bends and only one moderate straight and a few short chutes, so it takes a while to leam (years, if you are somewhat thick), and I was practically getting windbum from the younger Valencia regulars who were knee-skimming by me in Tum 1. Not to mention the flying endurance-racer Melissa, who passed me so often it felt like Groundhog Day.

But if you have to learn a course and gradually pick up speed, the 996R is the bike to do it on. The locomotive power is always there, brake feedback is superb and the chassis is on your side. And it just gets better the faster you go. Balance and rideability are Ducati’s secret weapons. You can use all the power and all the grip, nearly all the time.

The engine’s smoother-revving nature, however, makes it easy to hit the rev-limiter, which cuts in rather abruptly at 10,500 rpm, like tripping on your own shoelaces. You could hear the stutter-step of riders hitting it all over the track.

Meanwhile, back in the pits between sessions, I sat in a director’s chair, swilled some Gatorade and looked around. Most of the magazines had sent their resident hot-shoes, and I realized with alarm that most had not yet been bom the year I got home from Vietnam. And I was the only one with a gray beard. And glasses. Bifocals at that. “Am I getting old, or do I need more track time?” I asked myself.

More track time, of course, is always the answer.

Fine as the 996R is on the track, I am puzzled by Ducati’s strategy of keeping this new performance package limited to a handful of sold-out bikes. A standard 996, with stock canisters and chip, is virtually the slowest front-line repli-racer you can buy at or above the 600cc displacement level. Why dole out performance improvements so frugally? The Japanese have us drowning in annual horsepower increases, at bargain prices. So why $26,000 for an improved version of a veteran model? I don’t get it. But if Ducati would add these improvements to the base-level 996, I’d probably buy another one. Maybe they will.

After our track day, a dire weather forecast of cold rain and high winds threatened our ride into the mountains, but Kent, Melissa and I bundled up and left anyway on a slightly tmncated route with two Spanish Ducati reps. We lucked out, and only a few gusts of rain came out of the uncertain sky.

Our star bikes for this ride were the retro-styled MH900e and the new Monster S4, with its liquid-cooled 916 engine. I started out on the Monster.

This bike, already known for wearing its mechanical heart on its sleeve, is now busier than ever with exposed hoses and wires. Not a pretty thing, it is essentially an ST4 with Monster bodywork, so it now has an exposed radiator across the front and a white plastic catch-bottle nested between the cylinders.

But it is fun. And agile, thanks to the relatively wide bars and flattrack, elbows-out riding position.

With a claimed 101 bhp on tap at 8750 rpm, it moves out with rowdy lust and handles well in the dodgy urban traffic and on the tight, narrow mountain roads we attacked. Out on the open highway, it’s not so much in its element.

It’s a very fast bike with exceptionally tall gearing, but the riding position makes anything over about 75 mph a hang-on-and-leanforward affair. Also, the small fairing doesn’t deflect much wind. What it mostly does is flutter around alarmingly in the airflow. Needs better brackets. The bike also could do with lower gearing. Fifth and sixth gears are almost too tall to be useful on the highway, and we all found ourselves cruising in fourth a good part of the time, especially on mild hills or into the wind. Yet first is so tall, you have to slip the clutch to get rolling. An odd choice of sprockets (or gears) in an urban/backroad bike.

Other than that, the Monster S4 is comfortable and easy to ride, the dohc 916cc engine, re-tuned for torque and mileage, delivering power a bit more quietly and smoothly than the sohc 900cc air-cooled engine, without quite as much endearing thuddiness. Like the 996R, you can pick a gear and roll it on and off at will, blasting your way effortlessly through the mountains. Except when your seat comes loose from its moorings, which mine did three times. The catch release needed a minor adjustment back at the shop. Luckily, I was able to hold the seat in place, using the ancient Siamese art of prehensile cheek clenching, which is useful in a variety of emergencies.

In a small mountain town we swapped bikes, and I found myself on the MH900e.

When Pierre Terblanche designed this thing, he was trying to evoke the elemental, spidery lightness of the old beveldrive 900SS in an aesthetically pure package. In this, he has largely succeeded. The bike is loaded with beautiful details-polished triple-clamps and headlight surround, exquisite fairing mounts, fluted gas cap, etc. It’s a piece of jewelry.

"To hang around Ben Dostrom is to become a fan. He's a thoughtful, articulate guy with a good sense of humor and no pretensions."

But it almost succeeds in being more than that.

On the road, the MH exudes personality. It has a lovely, if legally mandated too-muted exhaust note, and the chassis has a wonderfully light and narrow feel, with excellent rightnow pull from the air-cooled two-valve engine. Not as much power as the 996, but excellent torque and creamy throttle response. Ducati really has its fuelinjection dialed-in.

The longish bike has easy, shark-like stability in fast sweepers, but its modem chassis geometry makes it much nimbler than

any Hailwood-era Ducati, with relatively quick, neutral steering in the tight stuff. The ride is moderately stiff, and a really bad bump can cause the rear suspension to pitch you skyward, but the fork and shock handle most road patter without drama. Again, it’s nowhere near as stiff as an old beveldrive SS. It is functionally a pleasingly modem bike, with an overlay of vintage simplicity.

Too bad, though, about the riding position. The otherwisecomfortable seat is so high that, at 6-feet, 1 -inch tall with a 34-inch inseam, I can just get my toes on the ground, and the bars are correspondingly dropped on the forks. It’s a butt-up, head-down riding position that will challenge the most masochistic Ducatis ti. With an Aerostitch suit and scarf on, I could barely bend my neck back far enough to see around uphill comers in the mountains. A Ducati rep told me, “This is a bike for purists, who understood the old 900SS.” But no original 900SS (I’ve owned three of them) was ever this extreme-or tall.

Another drawback is a gas tank that holds only 2.3 gallons, like an older Sportster. Also, the mirrors are absolutely useless-except to view a small patch of blurred pavement on either side of the rear wheel.

Still, if the seat were about 4 inches lower, this just might be my favorite Ducati of all time. (There’s a huge amount of empty space between the seat and the rear tire; maybe some of that could be used.) I don’t care much for the fake finned “sump” under the engine and a few other art-beforefunction touches, but the chassis and engine are a sweet combination of age-old Ducati virtues brought up to date. This bike is on the right track. It just needs to be a) available and b) slightly more real-world in its ergonomics. Or even race-world. Like the 996R, the Hailwoods were all sold out over the ’net last year.

With the weekend came the World Superbike races. We were told by our Ducati friends that Spanish fans are so Grand Prix crazy, there’s not much interest in Superbike racing, so the crowds would be moderate. They were right,

even though this was the first big race of the season. The stands were as empty as Daytona’s.

Ducati’s A-team factory lineup included Australian Troy Bayliss, American Ben Bostrom and Spaniard Ruben Xaus. In qualifying, the Ducatis were quick, but it was clear the Aprilias were going to be the bikes to beat, particularly Troy Corser’s.

World Superbike uses Superpole qualifying to sort out the grid for the 16 fastest riders in early timed sessions. This system, in which grid positions are determined by one flying PHOTO BY MARK WERNHAM lap, is not terribly popular among some of the riders. It puts a lot of pressure on them to do one lap just right. But it’s thrilling for the crowd because frequent tire changes, brake bedding and warm-up laps in normal qualifying sometimes make it impossible to figure out who’s on a hot lap. With Superpole, there’s no doubt. The spotlight is on.

I talked to Bostrom for a while in the Ducati garage, and he seemed to be looking forward to it. To hang around Bostrom for a few days in the pits, incidentally, is to become a fan. He’s a thoughtful, articulate guy with a good sense of humor and no pretensions. (My grandmother would say he was “raised right.”) Watching him ride and slide both ends of the bike into a comer, or lean it over farther than seems physically possible, can also lead to fanship.

Bayliss is a pleasant guy and a hell of a rider, too, but the Ducati effort was not enough to keep Corser’s Aprilia from running away with both heats. Bayliss and Bostrom finished second and third in the first heat and Bayliss managed a second in the second heat as well. Spaniard Gregorio Lavilla rode a ferocious race to put his Kawasaki in a crowd-pleasing third.

Bostrom told me he was flagged in for jumping the start of the second race, then called in again for speeding in the pits, just as he accelerated over the magic line. Two laps down, he parked it. Why bum up a motor and tires? No doubt his luck will be better in the next one.

And maybe Ducati’s, as well. It’s going to be an interesting year, as we enter what is probably World Superbike’s sunset era, with the GPs going four-stroke. If it goes away, I’ll miss it. I like World Superbike’s connection to the street, and to the bikes I’ve owned. WSB has been good for VTwins from Italy. And vice versa.

It was 10 p.m. and pitch dark when I returned to my frigid car in the Madison airport, after 24 hours of flying and flight delays. Too late to go to a motorcycle shop and ponder which sportbike I need this summer to do a few track days. But on the drive home, I passed the Ducati/Kawasaki shop, its signs in the darkened windows reflecting off the slowly melting snow. Mañana, perhaps.

More track time, as we know, is always the answer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

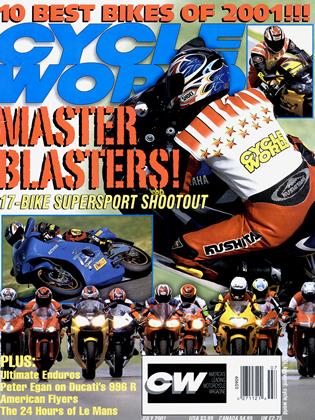

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCUp On the Roof

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles