CALM AMID CARNAGE

RACE WATCH

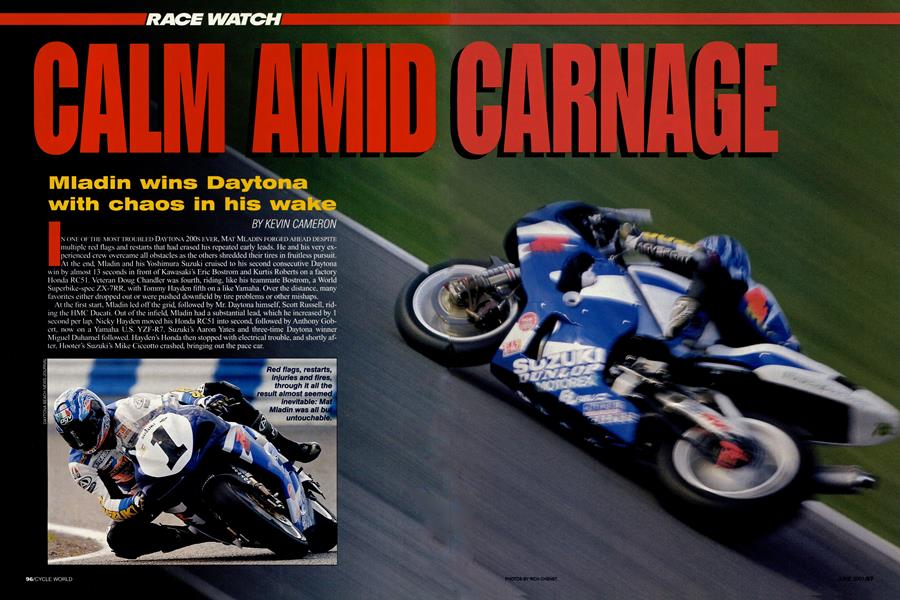

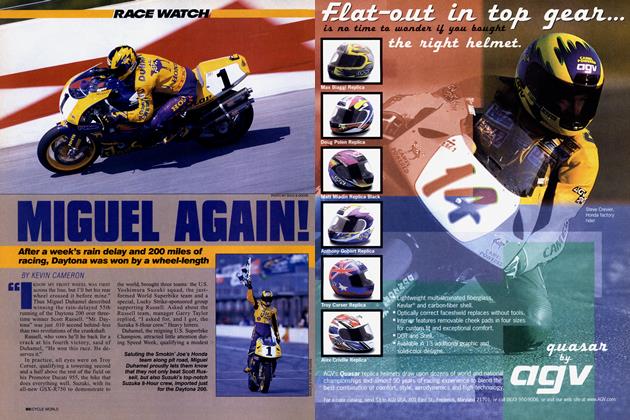

Mladin wins Daytona with chaos in his wake

KEVIN CAMERON

IN ONE OF THE MOST TROUBLED DAYTONA 200s EVER, MAT MLADIN FORGED AHEAD DESPITE multiltiple red flags and restarts that had erased his repeated early leads. He and his very experienced crew overcame all obstacles as the others shredded their tires in fruitless pursuit.

At the end, Mkidin and his Yoshimura Suzuki cruised to his second consecutive Daytona will by almost 13 seconds in front of Kawasaki's Eric I3ostrom and Kurtis Roberts on a factory I londa R('5 I Veteran E)oug (`handler was lburth, riding, like his teammate Bostrom, a World Superbike-spee ZX-7RR. with Tommy I layden fIfth on a like Yamaha. Over the distance, man lavonles either dropped out or were pushed downfIeld by tire problems or other mishaps. At the first start, Miadin led oil the grid, lollowed by Mr. I)aytona himself~ Scott Russell, riding the I IMC Ducati. Out of the infIeld. Mladin had a substantial lead, which he increased by I second per lap. N icky Hayden moved his Elonda RC5 I into second, followed by Anthony Gobcr1, now on a Yamaha IJ.S. YZF-R7. Suzuki's Aaron Yates and three-time I)aytona winner Miguel Duhamel followed. I layden's I londa then stopped with electrical trouble, and shortly aflet', I looter's Suzuki's Mike (`iccotto crashed, bringing out the pace car.

Because in the bright sun the orange pace-car flag was hard to distinguish from a yellow flag, some riders slowed while others held position at speed. Teammates Jamie Hacking and Yates collided on the approach to the chicane, smashing to the ground two-thirds of the Yoshimura Suzuki effort. Both were

out of the race. Roberts’ Honda-and his hand-was damaged as Yates’ bike hit his, a cut tire and bent wheel the worst of the fairly extensive damage to the RC51. The red flag was thrown.

The restart front row was Mladin, Roberts, Duhamel and Gobert. At the green flag, Mladin won the drag

ace again, but Russell’s 996 stalled on the line. He raised his hand and began to dog-paddle off the grid, but was hit from behind by Dean Mizdal and Richie Morris in a sickening one-two collision. Mizdal and Morris were both injured, but Russell got the worst of it, suffering a severely broken arm and leg. Another red flag. Extinguishers dealt with the resulting gasoline fire and three ambulances dominated pit road for a long time.

Time passed and the shade began to creep back from the edge of the pit-wall tenting. Bostrom stretched, sitting in front of an electric fan. Mladin looked remarkably relaxed, his usual race face absent. At last, the track was declared ready. Mladin again won the start, followed by Duhamel, and began to ease away, but at a slower rate than before. The repeated stoppages had afforded other teams new opportunities to improve their setups. On lap eight, Roberts pitted to replace a vibrating, blistering tire, and two laps later, Gobert's chain shed its rivet link (that's not supposed to happen!), setting these men back. On lap 14, Larry Pegram, who had been ex tremely fast through practice, crashed his Competition Accessories Ducati into the haybales in the chicane, setting them afire. This required an actual fire engine and more time spent not racing.

During this long break, top teams changed clutches (most are good for only two hot starts), updated their set ups and changed tires. This left 42 laps to go. In a normal Daytona 200 of 57 laps, the first fuel stop is

made at 19 to 21 laps. Because Superbikes go 14 or more miles per gallon of fuel, this restart distance could be run with a single stop for gas-but only if a given motorcycle could go that far on a set of tires.

The restart front row was Mladin, Duhamel, Bostrom and HMC Ducati’s Steve Rapp. Rapp’s 996, however, was damaged by a collision during the earlier pace-car debacle, leading to an alternator failure. Unable to repair the bike in time for the restart, he rejoined a lap down on a backup machine. It was clear that the others had gained speed from the break, and on lap 17, Duhamel put his > Honda into the lead, provoking a mighty shout from the surprisingly populated grandstands. Now Duhamel, Roberts, Bostrom and Miadin pulled rapidly away from the pack. Four laps later, Roberts also passed Miadin to take second. It wasn't to last, for both Hondas were soon

in tire trouble. About lap 26, Miadin repassed Roberts, who then pitted pre maturely for tires. This, coming so early into the restart, would force him to make a second time-consuming gas stop less than 10 laps from the end. By mid-race, Miadin had overcome Duhamel's Honda,

which was now sliding visibly. Not long after, Duhamel “crossed the bars” and low-sided going out onto the banking in Turn 6. He restarted and rode to his pit to repair damaged controls, whereupon a leaking radiator was discovered as well. Race over, he stormed out of the pits and left the track early.

Meanwhile, Mladin had made his scheduled stop for two tires and fuel, stationary for only 11.4 seconds. Gobert, restarting on a backup bike (the old one’s crankcase was broken by the failed chain) at the back of the grief suffered an explosively chunking rear tire while traveling at near-top whack on the banking. Amazingly, despite the huge, high-speed slide, Gobert didn’t crash, but the impact of the flying rubber destroyed wiring, stopping his ride. He was visibly shaken.

Mladin now led by nearly 18 seconds. Nicky Hayden had restarted two laps down after his earlier electrical trouble and was hewing his way forward. By lap 48, he had risen to 18th! Mladin was content to let Roberts, now second, eat slowly into his lead. The leader’s job was now to hold position, cope with unpredictable moves by> lapped riders and conserve tire condition by use of minimum throttle. Man and motorcycle cruised on to the flag. At the end, evening was at hand. It had been a long day.

What happens at Daytona is not random events. Tires blister and chunk because they get too hot, and the reasons go beyond the worn out complaints of “bad tire” or “bad batch.” Mladin completely dominated practice and was able to push to the front after every restart because he and his experienced team know how to make even a brand-new racebike go fast without eating its tires. Other riders were as fast or faster in the race-but they failed to keep tires on their bikes and either lost time in the pits or fell by the wayside.

Mladin has worked with the same core crew for years now. That enabled him to quickly get his fine-tuning done on Wednesday, the first day of practice. This included final choice of spring and damping rates, a taller seat, handiebar adjustments and constant moni toring of tire temperatures by Dunlop technicians. He worked in hot, two-lap tests, riding hard to get meaningful information, and in 29 practice laps had made 13 stops and readjustments. Every move had a purpose. Informa tion is speed, and this team was quick-

est at getting it. Miadin's lap times dropped steadily. Meanwhile, other teams were strug gling-Russell with a fork problem, Honda with the lack of rear grip that has plagued the RC5 1 since the middle of last season, Gobert with yet another new ride and new team. Aaron Slight, newly on the Competition Accessories Ducati in place of John Kocinski, wisely spent his practice time getting to terms with the bike in long blocks of laps (his bike would be out of the race on lap 28, though, with a dropped valve).

In Thursday qualifying, Mladin went straight to the point, breaking Gobert’s two-year-old lap record with a 1:48.424. Gobert’s best on the Suzuka 8-Hourtype YZF-R7 (with deliciously noisy gear-driven cams!) was a very impressive 1:48.663. Nicky Hayden’s 1:48.765 was the only other time in the 48s. Mladin had hoped for an even better time, but as last year, was unable to get the extremely temperature-sensitive qualifying tires to maintain grip for a whole lap. “It’s hard to get more out of a tire that’s not actually round for the last part of a lap,” he noted.

Every machine in the top 10 qualifiers at Daytona has the power and reliability to win the race, but only a machine and rider that can go fast with acceptable tire temperatures can win. Bravura riding can qualify well and lead the race, but it seldom wins.

Mladin’s Suzuki was not always so good. In his first Daytona rides, his

drives out onto the banking from Turn 6 were slowed by wheelspin, while Duhamel's old V-Four Honda RC45 hooked up and accelerated. Since then, the Suzuki's powerband has changed, making it less likely to tach out over rough pavement. I suspect also that me-

thodical work by Mladin and Yoshimura data-acquisition expert Ammar Bazazz has allowed use of a softer, more tire friendly suspension setup. Now, the tire spinning roles are reversed. The very powerful Honda RC5 1 V-Twins of Duhamel, Roberts and Nicky Hayden> are loose at the back, these riders forced to hang the rear tire out and spin it, while Mladin hooked up and went forward.

This brings us to a basic problem in racing: trouble with the home office. Harley-Davidson, in the throes of a rac-

ing-department reorganization, seems unsure whether it needs more meetings and managers or more horsepower and handling. They aren’t the only ones. Why does the Honda lack rear grip? No one comes right out and says it, but it

seems there is a disagreement between engineering in Japan and trackside people here in the U.S. The U.S. staff solved the rear-grip problem with the RC45, but that very success may ban any attempt to try the same on the RC51. If so, this would not be the first time that corporate management preferred defeat to admission of fallibility.

It is almost as though the more money is spent, and the more engineers put on a project, the less is achieved. Aerospace giant Lockheed recognized this when it gave the most critical projects to its “skunk works,” a close-knit small group that produced unusual and outstanding aircraft such as the SR-71. Small groups retain a coherent view of their project. Large groups fragment into separate departments whose separateness must then be “repaired” by endless memos and meetings. This waste of time is called “communications,” and requires its own managers and large budget. In terms of speed per > dollar, the home-built Britten motorcy cle must rank among the all-time greats. More engineers are not the answer to racing problems. Most lack trackside experience, which takes years of real (as opposed to academic) study to ac

quire. Trackside work is often seen as manual labor, beneath the status of de gree-holders. While engineering does use science to solve practical problems, the neat formulae learned in engineer ing schools fray at the edges in racing.

It’s not that the laws of physics don’t apply, but rather that the variables get tangled in a way that resists formal analysis. Analysis takes time that racing usually can’t afford. As legendary tuner Erv Kanemoto once said, “In racing, there’s barely time to find out how. There’s no time to find out why.”

Why didn’t Honda just fix its grip problem? Here is a possible scenario: If a motorcycle’s swingarm pivot is in the wrong place, as the rider applies power to accelerate out of corners, weight transfer squats the machine down at the rear. This takes weight off the front, causing it to push and the machine to run wide. The harder the rider turns the throttle, the more the machine runs to the outside. The correct fix is to reposition the pivot so that the vertical component of chain pull force opposes this natural squat. Then, the machine remains level and steers out of corners > normally. But what if, as in the case of the Ducati, the swingarm pivot is part of the engine, and can't be moved without obvious major surgery or worse-re-ho mologation with new parts? Or worse yet, what if the swingarm pivot is off limits because of a corporate decision? The simplest alternative "fix" is to in-

crease rear spring rate enough to over power the squat, or to put a suspension rate rise into the rear linkage at the crit ical point. Both make rear suspension over-stiff, resulting in sliding and skat ing on rough corners. When the under lying geometry is right, softer suspen sion can be used, resulting in better grip

and improved tire life. This is a simplifi cation of a complex problem, but every team must deal with it somehow. Anoth er of the Big Four spent millions in an attempt to write software to solve this problem explicitly, but gave up with no end in sight. In other words, it was left to the trackside people.

Why are Miadin and his team able to cope now? Miadin rode what Suzuki ini tially gave him to the limit of his consid erable ability, and when Bazazz added scientific methodology and computer/instrumentation skills, the already capable team took off. Now, with the highly ex perienced Peter Doyle as crew chief and Bazazz able to concentrate on instru mentation, even more is possible. This showed with how quickly the team got the new-generation GSX-R750 Super-

bike up to speed (Miadin raced the `99 version last year). When you get results, your factory may begin to trust you, and that trust may be expressed as greater freedom to experiment. I say "may" be cause this is a sometimes thing. Ideally, the trackside people rely on the factory's analytical powers to produce reliable, fast and approximately correct motorcycles, and the factory then relies on its trackside people’s experience to complete the machine’s adaptation to the rider, the track and the day. When the partnership works, it’s good.

After the race, journalists asked Mladin why he wasn’t more concerned about Roberts and Duhamel being ahead of him so long, Roberts possibly blocking Mladin so Duhamel could get away.

“I could see his (Roberts’) tire was spinning up. He was holding me up, really. When his tire started forming that black line, I knew. I got by him and then it wasn’t long (until he passed Duhamel).”

Of Duhamel’s Honda, Mladin said, much in the same way as he might have taken note of any other irrelevant but remarkable property, such as it, say, being painted hot pink, “It was awful fast.” At Daytona, fast is irrelevant if the cost of that speed is excessive tire wear.

Mladin’s impressive personal discipline usually holds him rigidly in “interview mode” when talking to the press, but we got a glimpse of the hot core within for just a moment.

“They talk about the youngsters?” the 29-year-old asked rhetorically, eyebrows rising. “We put it on ’em. And in two-and-a-half months (when racing resumes), we’ll put it on ’em again. I’m motivated. I intend to come back next year and do the same, and the year after that.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTrouble By the Beach

June 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsAt the Edge of Magic

June 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving Museum

June 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupComing Soon: Next Year's Knockouts

June 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFuture-Think Mxer

June 2001 By Jimmy Lewis