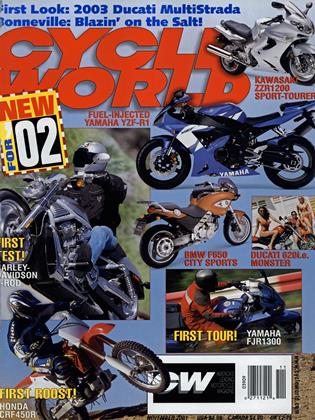

HondaCR250RC RF450R

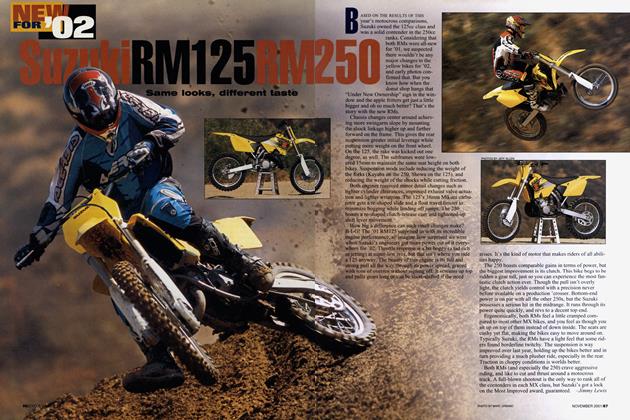

NEW FOR '02

Getting the dirt on high-tech

JIMMY LEWIS

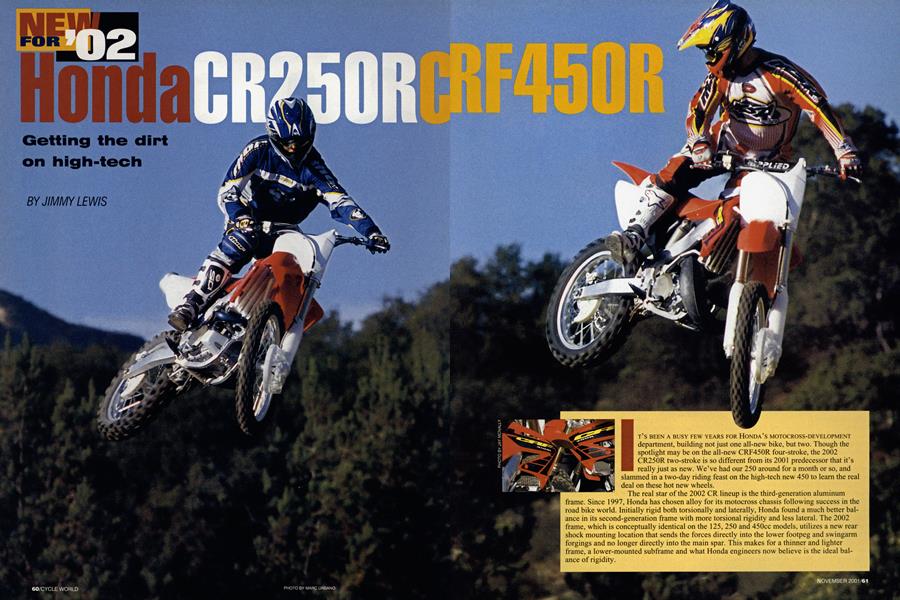

T’S BEEN A BUSY FEW YEARS FOR HONDA’S MOTOCROSS-DEVELOPMENT department, building not just one all-new bike, but two. Though the spotlight may be on the all-new CRF450R four-stroke, the 2002 CR250R two-stroke is so different from its 2001 predecessor that it’s really just as new. We’ve had our 250 around for a month or so, and slammed in a two-day riding feast on the high-tech new 450 to learn the real deal on these hot new wheels.

The real star of the 2002 CR lineup is the third-generation aluminum frame. Since 1997, Honda has chosen alloy for its motocross chassis following success in the road bike world. Initially rigid both torsionally and laterally, Honda found a much better balance in its second-generation frame with more torsional rigidity and less lateral. The 2002 frame, which is conceptually identical on the 125, 250 and 450cc models, utilizes a new rear shock mounting location that sends the forces directly into the lower footpeg and swingarm forgings and no longer directly into the main spar. This makes for a thinner and lighter frame, a lower-mounted subframe and what Honda engineers now believe is the ideal balance of rigidity.

Though the frames may be the same in principle, the bikes themselves couldn’t be more different. Even the design teams were completely separate due to the short time schedule in which the 450 had to be developed. Minute changes to things like the front fender, swingarm angle, shock linkage and foam air filter may elude the eye more than the obviously different engines.

Encased in the CRF's motor are all of the good four-stroke ideas from the past decade, and then some. Seen before from Hus~vama is a reed valve in the oil circuitry. and from

Cannondale the modern application of separate transmission and crankcase lubrication. The single overhead cam is popu lar now that a few European manufacturers have proved that dohc is not the only road to high power. Honda just put its own twists on all of these concepts.

Most notable is the Unicam. Its two outer lobes run on top of shim-under-bucket titanium intake valves, while its single center lobe actuates the steel exhaust valves via a forked rocker. This allows a flat combustion chamber and a compact valvetrain. Auto-decompression on the cam makes for brain less starting.

The oiling system could best be described as "semi-wet sump." It isolates the crankshaft in its own chamber, with one opening in the bottom of the case blocked by a one-way

reed valve. The oil is pumped in through the crank center and excess is blown out by piston pressure on the down stroke, in effect creating a negatively pressurized crankcase.

This aids in reducing compression braking, as well. The centercase-enclosed oil pump also sends oil up a cylinder stud to the cam, where it lubricates the vitals on top before falling down the camchain tunnel, past the ignition rotor and into a small sump to be collected. Total motor oil capacity is 700cc, and it is completely isolated from the tranny fluid.

The 450's transmission mirrors that of the two-stroke CR250 in design, but the ratios are different, and the clutch spins much faster to handle the increased torque loads. Also, the CRF uses steel plates in its clutch, as opposed to alu minum for the 250. The cavity in which the tranny is housed calls for two-stroke-type gear oil, though the proper motorcy cle-specific four-stroke motor oil can be used-just stay away from moly additives if you want to avoid premature clutch wear. This set-up keeps clutch contaminants out of the top end and burnt oil out of the transmission and clutch.

Honda's refinement here is in the simplicity of changing oil, as there's one drain for each cavity, one filler for each, and a simple two-bolt-access single oil filter for the crankcase. There's no draining oil from the frame, no danger of damaging external oil lines and no added weight from such systems.1

The CRF’s carburetor is a Keihin 40mm flatslide similar to the 39mm unit found on Yamaha’s YZ426F, but with a few Honda modifications. Most notable is the addition of a hotstart circuit that physically switches positions with the choke knob on the carb body. The hotstart is cable-actuated from the handlebar, which means that little lever above the clutch is not a compression release. A manual decompression system is available, but we’re not sure you’ll ever need it.

As for the CR250, going to case-reed induction for 2002 marks the first major breakaway in more than a decade. Honda claims the case reed provides a more direct route for fuel than the previous piston-port. This, in turn, makes for a better overall power spread. Also, there is extra room to have a larger reed cage and more flexibility in intake timing because the piston passing the intake port is no longer the determining factor.

To complement the new intake, the new RC (Revolutionary Control) exhaust valve is electronically actuated. The rotary-style valve and its circuitry are spin-offs of technology used on Honda’s NSR roadracers, as well as the experimental EXP2 rally racer. The ECU positions the valve based on engine speed, making for more precise control compared to mechanical versions. This also frees up space and drag inside the motor. Physically, the CR250’s powerplant looks as if a slice has been taken off the front-lower portion, and the ignition side shrink-wrapped.

So what are these two Hondas like to ride? We’ll start with the 250: Our first impression was that it’s not as changed as it would seem. The typical CR character remains intact in spite of the performance-increasing revisions.

Gearing is two teeth smaller on the rear sprocket, but the new bike pulls the same as the old one from idle in any gear. The power spread feels wider, starting earlier and pulling longer on top. Peak horsepower feels the same, with a little bit more on tap-as if you really needed it! But the big improvement is in the “fill” getting there. The new motor possesses far superior roll-on ability-no bogging and no snapping to life in a fury, unless you want it to. A snap of the clutch is all it takes to get the 250 on the pipe and cooking. Most of our test riders found the Honda extremely fast, and even those who hadn’t liked CR power before were very happy. The few riders who complained the bike felt slow came to their conclusion because they were revving it too much and spinning the rear tire excessively. Once they started riding a gear higher, they were all smiles. No wonder Honda changed the gearing.

Speaking of gears, change that tranny fluid after the first ride and often thereafter. Our CR250 wasn’t very happy in the shifting department until it had gotten a few tranny flushes. Also, the clutch took a while to get to the smooth action we’ve come to expect from Honda. With the newfound gear-high riding ability, the clutch takes some abuse, and needs to work flawlessly to complement the power.

Ours just took some break-in.

The next most noticeable thing about the 250 is the roomier riding position. As was the case with the CR125 on which we reported last month, you can get all over this bike and make it turn or stand up on command. The aluminum frame seems to transmit no more harshness than most of the more rigid steel frames. Credit the new design of the improved suspension, but it all blends in together.

Gone are the days of softly sprung moto-bikes. If you’re an average-weight rider, you’ll be right in the hunt in terms of spring rates. And while the Showa suspension’s near-infinite adjustability should keep Beginner to Pro happy, they shouldn’t need much tweaking: The new bike didn’t require a clicker change between seven different riders, weighing 140 to 200 pounds, on four different tracks. To be truthful, though, on the fifth track we added one click of compression all the way around and a quarter-turn less high-speed compression on the shock to deal with some big whoops and high-speed chop. But that’s a far cry from a few years ago, when every track and condition involved changing the clickers.

The CR250’s handling is typically neutral, with a bit more turning control at no cost in stability. But the biggest gain compared to past CRs is in choppy, sweeping turns, where the front end no longer refuses to bite and the rear end no longer steps out.

Now, what everyone is waiting for, the report on the CRF450R: Unfortunately, due to some bearing that didn’t pass durability muster on the initial press bikes, we were only allowed two days on the new four-stroke at a private track in Central California. Honda decided to keep the testbikes and will re-release them to the magazines as soon as the new production part can be installed. (Bikes heading to dealers will already have had this rectified.) This means we’re somewhat limited in our ability to draw conclusions for now.

But what we do know is that right from the first kick on the starter, this is the four-stroke CR we’ve been waiting for! And kick it is t

all you do-unless it’s cold, in which case you can pull the choke knob, too. And if it’s hot, you just pull the lever to open the hot-start circuit and kick like normal. It’s so simple, it makes starting a YZ426 seem like a religious ceremony.

After riding the CRF for a minute, our first thoughts were similar to when we rode the first YZ400F: This ain’t no fourstroke! Don't even think there is anything XR-like about it, it is right there in the trend of ultra-quick-revving Thumpers, with motocross-style power delivery all the way. And when you close the throttle, there’s less compression braking than

on any other four-stroke we've ridden. For some, this may overcome the biggest hurdle in riding Thumpers.

Power on again, and the CRF has more of a four-stroke pulse in the lower revs, feeling a bit more controlled than a YZ426; the CRF is more like a KTM here. As rpm rises, the Honda will rev almost as quickly as the Yamaha, but depending on gear selection will pull higher gears better, making it in turn rev slower. And it will rev long. The 11,200-rpm revlimit takes a bit more effort to hit than with other Thumpers, and since the meat of the power is in the 5000-9000-rpm range, there isn’t much sense in holding it up there.

And yes, it is blazingly fast, likely faster than most Openclass two-strokes. This is the first sub-500cc dirtbike we’ve ridden that repeatedly tried to flip the rider during third-gear roll-ons! But it’s so rideable that the rider was able to back off the throttle and come back into it without losing much ground or falling off the pipe. The only thing holding back the CRF will be traction, which it finds quite nicely.

Our testbike was sensitive to pilot-screw adjustments on the carb, but if it was out of tune, you could hear it, making a funny popping sound or seeming like it was hitting the revlimiter too early. Also, the CRF tended to backfire when landing from jumps or in choppy turns if you were hard on the gas, then let off for a second. It seems that the gas might pool in the intake and then pop as the throttle is cracked. The funny thing about this was that the rider didn't notice anything but the sound; the engine doesn’t stall or lunge or miss a beat, and the Honda technicians didn’t seem concerned.

The CRF450 is light, a reliable source claiming that 232 pounds is the real dry weight. It feels almost as light as a KTM, but without the twitchiness that often accompanies that feathery feel. And the CR carries its weight low, making for a flickable four-stroke. It isn’t as light as the CR250, though, and when the going gets really rough, you’d rather be on the two-stroke for sure. But the track we tested on was quite tight and a bit supercrossy, with a few deep sandy whoop sections-not the best place for the CRF450 to shine. It sure cleared the tight out-of-tum jumps well, though. Credit power and hookup.

In terms of handling, the CRF is very CR-like, coming much closer to a two-stroke than we thought a four-stroke could. The Honda's 2002 brakes establish a new benchmark, especially in the rear. The control is phenomenal, with power to spare. And the extra weight on the four-stroke’s front wheel makes the front binder that much better. It bites harder before making the tire skid, and the CRF’s extra weight isn’t an issue in slowing.

The 450’s Showa suspension again mirrors that of the 250 in most ways, but has a plusher feel. Its .47-kg fork springs are much stiffer than the .44-kg springs in the 250’s front end. Ditto the rear, where the 450 has a 5.4-kg spring compared to the 5.0-kg on the 250. Valving is different, and the 450’s slightly shorter shock rides through a different linkage.

On the 250, the swingarm was kicked down a bit to aid in bump compliancy, giving it a little more leverage when fully extended. This especially helps on braking, allowing the shock to work rather than deflect. The 450 likes a little stiffer initial setting on the shock spring preload, with 98mm of sag with the rider on board compared to 100mm-plus for the 250.

Overall, either of these CRs would make any motocross rider happy, and choosing between them is a matter of personal preference. Getting a 450 might be tough, however; we hear they’re going fast even though they’re not here yet! But those who have liked CRs in the past will flip over the CRF. It retains all of the good CR traits while adding a new style of Honda four-stroke feel to the mix. And although it will take more time on the 450 to see how it really stacks up against the competition, we wouldn’t bet against it. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAfter the Fall

November 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFirst Bikes

November 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupSneak Peek! 2003 Ducati Multistrada

November 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupOld Pro, New Suspension

November 2001 By Allan Girdler