Clipboard

RACE WATCHA

CW Catches Salt Fever

Downcourse, bright-orange mile markers appear as specks on the horizon. In succession, each dot grows in size to that of a roadside postal drop box as I rush past. With luck, I’ll be haulin’ the mail in excess of 200 mph through the final timed mile of the 5-mile course at Bonneville’s National Speed Week.

On the vast salt flat, the earth’s curvature obscures one’s view of the finish line from the starting area; the action that takes place between these points is both soulstirring and dangerously addictive. I’ve never felt so alone while at speed, or so enveloped by it. While Bonneville’s white, barren landscape filters the visual sensation of high-speed motion, other senses tell a different story. We’re bookin’!

Pinned in top gear, the bike slithers and weaves under power as its rear tire hunts for grip on the snow-white sur face. I study the rev-counter, looking for the slightest hint of rpm gain while tightening my tuck behind the fairing. Scanning the path ahead, I adjust my line to avoid hitting speed-sapping soft spots in the salt. A rider keeps very busy throughout the run.

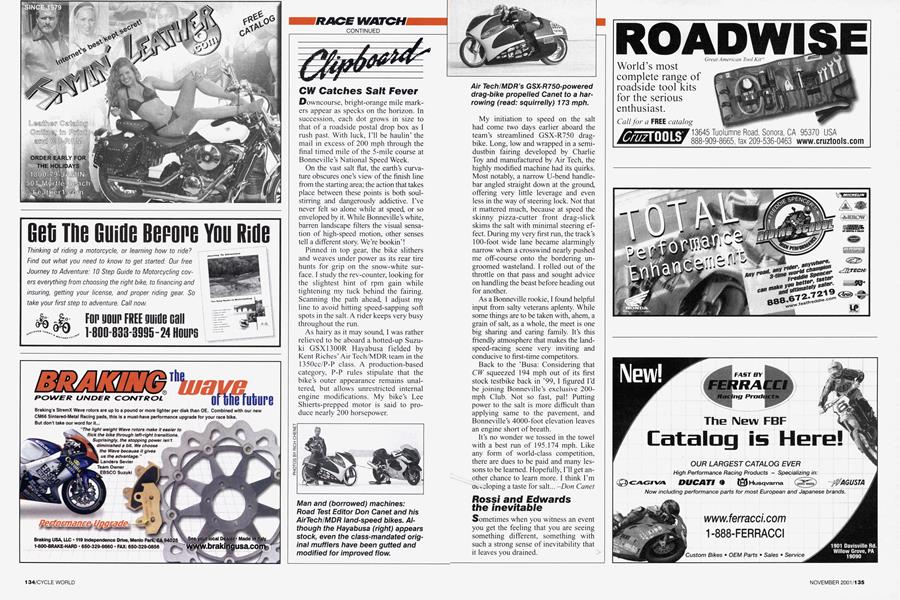

As hairy as it may sound, I was rather relieved to be aboard a hotted-up Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa fielded by Kent Riches’Air Tech/MDR team in the I35()cc/P-P class. A production-based category, P-P rules stipulate that the bike’s outer appearance remains unaltered, but allows unrestricted internal engine modifications. My bike’s Lee Shierts-prepped motor is said to produce nearly 200 horsepower.

My initiation to speed on the salt had come two days earlier aboard the team’s streamlined GSX-R750 dragbike. Long, low and wrapped in a semidustbin fairing developed by Charlie Toy and manufactured by Air Tech, the highly modified machine had its quirks. Most notably, a narrow U-bend handlebar angled straight down at the ground, offering very little leverage and even less in the way of steering lock. Not that it mattered much, because at speed the skinny pizza-cutter front drag-slick skims the salt with minimal steering effect. During my very first run, the track’s 100-foot wide lane became alarmingly narrow when a crosswind nearly pushed me off-course onto the bordering ungroomed wasteland. I rolled out of the throttle on that pass and sought advice on handling the beast before heading out for another.

As a Bonneville rookie, I found helpful input from salty veterans aplenty. While some things are to be taken with, ahem, a grain of salt, as a whole, the meet is one big sharing and caring family. It’s this friendly atmosphere that makes the landspeed-racing scene very inviting and conducive to first-time competitors.

Back to the ’Busa: Considering that CW squeezed 194 mph out of its first stock testbike back in ’99, I figured I’d be joining Bonneville’s exclusive 200mph Club. Not so fast, pal! Putting power to the salt is more difficult than applying same to the pavement, and Bonneville’s 4000-foot elevation leaves an engine short of breath.

It’s no wonder we tossed in the towel with a best run of 195.174 mph. Like any form of world-class competition, there are dues to be paid and many lessons to be learned. Hopefully, I’ll get another chance to learn more. I think I’m acveloping a taste for salt... -Don Canet

Rossi and Edwards the inevitable

Sometimes when you witness an event you get the feeling that you are seeing something different, something with such a strong sense of inevitability that it leaves you drained.

Such was the case with the Suzuka 8 Hours this year. One brief walk through the pits in the days leading up to the race would have left you with that feeling of inevitability: There was such a sense of confidence in the Cabin Honda pit, it was almost hysterical. All you had to do was look at the Honda garages, at the smartly dressed engineers, at the motorcycles, the prep for which goes beyond “methodical” and into the regions of “beautiful.”

Team sponsor Cabin cigarettes, part of the Japan Tobacco empire, had clearly spared no expense and was quite keen that everyone knew what name was on the side of the bike. Everything was painted in the corporate colors (a curiously Marlboro-like red) from the carpet on up.

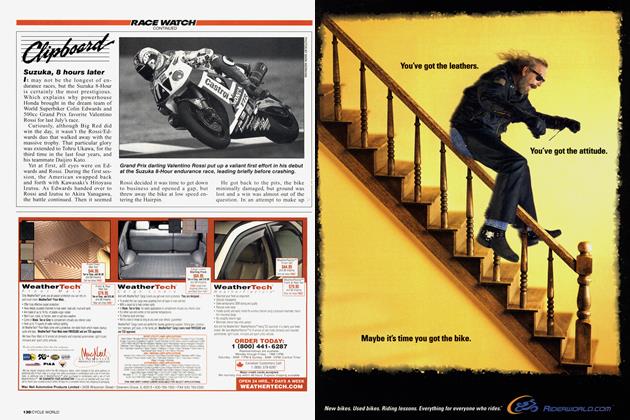

Honda brought together one of the strongest rider line-ups imaginable, drawing from its top Grand Prix and World Superbike stars. Valentino Rossi teamed with Colin Edwards, Tadayuki Okada with Alex Barros, and Tohru Ukawa with Daijiro Kato. Any one of these three pairings could easily have won the race, and among all the riders only Rossi hadn’t been a winner in the 8 Hours before!

They say the beauty of racing is that nothing is certain, but there was going to have to be something big to stop the Honda juggernaut.

Honda has typically fielded three or four factory bikes, with only one really intended to be the victor, the others nothing more than spoilers against the other factory teams. This year, there were no apparent spoilers-all three teams were potential winners, although many thought that ultimately Edwards and Rossi would be given the best chance by Honda. If recent 8 Hours races had lacked anything, it was top-level GP riders, and having a big name like Rossi atop the podium would help keep up the prestige of the race. The interesting point here is that, post-race, it has been suggested that Barros felt the pit stops were rigged so that the final result was created in the boardroom, not on the track, which is a pretty strong charge against the people who write his paycheck. But it also seems unlikely that the very popular Rossi would not be helped in every way to take his first win.

In the face of such a massive Honda production, all but Suzuki failed in their assault. Kawasaki’s Akira Yanagawa was the first to fall, running into a backmarker who missed a gear driving out of the chicane. Teammate Hitoyasu Izutsu finished the job when he crashed the same bike with two hours to go. Gregorio Lavilia crashed the sister Kawasaki midway through, and Noriyuki Haga dropped the Yamaha from fifth place with an hour to go-he and teammate Anthony Gobert hit the showers early.

The Suzuki of Akira Ryo and Yukio Kagayama saved the day for the rest of the non-Honda world. They started from pole and led the first lap, but were pushed out of the lead by the Honda showcase and the fight of the 8 Hours was ultimately between the Hondas of Okada/Barros and Rossi/Edwards. Midway through, “endurance” racing was put aside and a sort of Superbike Grand Prix took place for a couple of hours. Okada and Rossi started it, and the result was a rather messy clash at the chicane which saw Okada fall off and Rossi go straight. The impressive thing was that Okada picked up the bike and the pace to close back up on Rossi-not an easy thing to do!

When the next pit stops were over, Edwards was still ahead of Barros, but they were tangled in a duel that probably upset HRC-potentially a disaster if they took each other out.

When the riders swapped over in late pit stops once again, Rossi suddenly held a significant lead and he (and teammate Edwards) went on to win with the Suzuki third. Perhaps Barros had a point...

-Mark Wernham

John Deacon, 1963-2001

British off-road racer John Deacon was killed while competing in the Master Rally in Syria on August 8. During a special stage he apparently got off course, crashed and fell oft' a cliff. Though a medical helicopter was on the scene soon after, the former factory BMW rider had already passed. He leaves behind a wife and two children.

Deacon was a member of the BMW squad for the past two years. He was competing in the Master Rally on a privateer R900RR, as BMW had pulled out of off-road racing after the 2001 Dakar Rally. During his long career, the well-liked Brit was a 10-time British four-stroke enduro champion and earned nine gold and three silver medals at the International Six Day Enduro. This year he was sixth overall in the Dakar Rally, winning the twincylinder class and matching his previous best finish in the 1999 event.

I’d competed against Deacon since the "89 ISDE, but really got to know him during our first Dakar together in ’96. On one of the early long stages, I came upon him out of gas in the middle of the desert and “loaned” him a few liters. As two of only a few English speakers in the rally, we gravitated toward each other, and his high-energy and cheerful attitude, even in the worst of conditions, could brighten the most awful days. Sadly, he retired midway through the rally with a broken collarbone.

During the past two years, we spent a fair amount of time developing the BMW Twin for rally duty and racing the Dakar and Dubai rallies with the team. Deacon loved to get out of Britain’s wet climate and into the desert where he could hold the throttle wide-open. Oddly enough, he looked at Dakar-as torturous as it is-as sort of a vacation. After all, it wasn’t sleeting.

-Jimmy Lewis

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAfter the Fall

November 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFirst Bikes

November 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupSneak Peek! 2003 Ducati Multistrada

November 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

November 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupOld Pro, New Suspension

November 2001 By Allan Girdler