Dr. T, remembered

UP FRONT

David Edwards

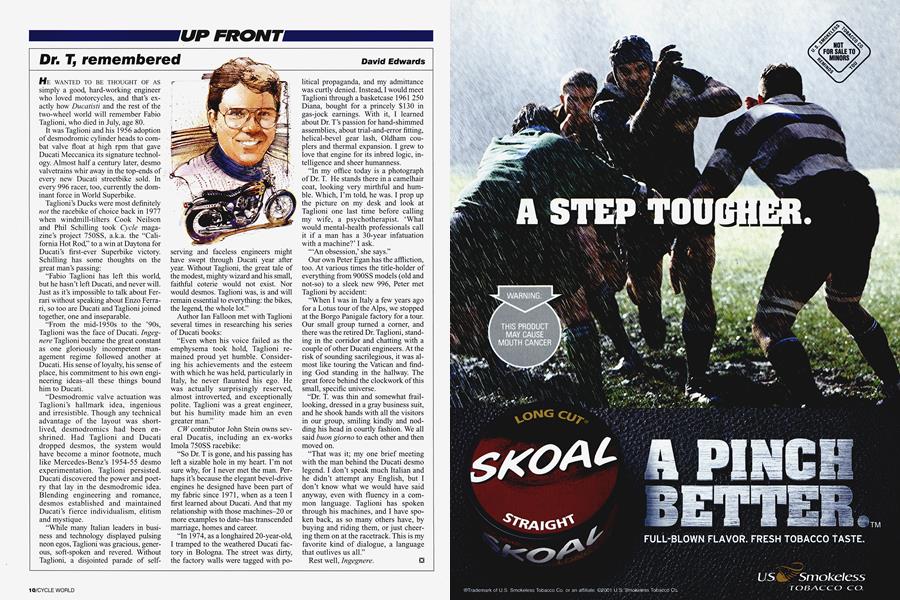

HE WANTED TO BE THOUGHT OF AS simply a good, hard-working engineer who loved motorcycles, and that’s exactly how Ducatisti and the rest of the two-wheel world will remember Fabio Taglioni, who died in July, age 80.

It was Taglioni and his 1956 adoption of desmodromic cylinder heads to combat valve float at high rpm that gave Ducati Meccanica its signature technology. Almost half a century later, desmo valvetrains whir away in the top-ends of every new Ducati streetbike sold. In every 996 racer, too, currently the dominant force in World Superbike.

Taglioni’s Ducks were most definitely not the racebike of choice back in 1977 when windmill-tilters Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling took Cycle magazine’s project 750SS, a.k.a. the “California Hot Rod,” to a win at Daytona for Ducati’s first-ever Superbike victory. Schilling has some thoughts on the great man’s passing:

“Fabio Taglioni has left this world, but he hasn’t left Ducati, and never will. Just as it’s impossible to talk about Ferrari without speaking about Enzo Ferrari, so too are Ducati and Taglioni joined together, one and inseparable.

“From the mid-1950s to the ’90s, Taglioni was the face of Ducati. Ingegnere Taglioni became the great constant as one gloriously incompetent management regime followed another at Ducati. His sense of loyalty, his sense of place, his commitment to his own engineering ideas-all these things bound him to Ducati.

“Desmodromic valve actuation was Taglioni’s hallmark idea, ingenious and irresistible. Though any technical advantage of the layout was shortlived, desmodromics had been enshrined. Had Taglioni and Ducati dropped desmos, the system would have become a minor footnote, much like Mercedes-Benz’s 1954-55 desmo experimentation. Taglioni persisted. Ducati discovered the power and poetry that lay in the desmodromic idea. Blending engineering and romance, desmos established and maintained Ducati’s fierce individualism, elitism and mystique.

“While many Italian leaders in business and technology displayed pulsing neon egos, Taglioni was gracious, generous, soft-spoken and revered. Without Taglioni, a disjointed parade of selfserving and faceless engineers might have swept through Ducati year after year. Without Taglioni, the great tale of the modest, mighty wizard and his small, faithful coterie would not exist. Nor would desmos. Taglioni was, is and will remain essential to everything: the bikes, the legend, the whole lot.”

Author Ian Falloon met with Taglioni several times in researching his series of Ducati books:

“Even when his voice failed as the emphysema took hold, Taglioni remained proud yet humble. Considering his achievements and the esteem with which he was held, particularly in Italy, he never flaunted his ego. He was actually surprisingly reserved, almost introverted, and exceptionally polite. Taglioni was a great engineer, but his humility made him an even greater man.”

CW contributor John Stein owns several Ducatis, including an ex-works Imola 750SS racebike:

“So Dr. T is gone, and his passing has left a sizable hole in my heart. I’m not sure why, for I never met the man. Perhaps it’s because the elegant bevel-drive engines he designed have been part of my fabric since 1971, when as a teen I first learned about Ducati. And that my relationship with those machines-20 or more examples to date-has transcended marriage, homes and career.

“In 1974, as a longhaired 20-year-old, I tramped to the weathered Ducati factory in Bologna. The street was dirty, the factory walls were tagged with political propaganda, and my admittance was curtly denied. Instead, I would meet Taglioni through a basketcase 1961 250 Diana, bought for a princely $130 in gas-jock earnings. With it, I learned about Dr. T’s passion for hand-shimmed assemblies, about trial-and-error fitting, helical-bevel gear lash, Oldham couplers and thermal expansion. I grew to love that engine for its inbred logic, intelligence and sheer humanness.

“In my office today is a photograph of Dr. T. He stands there in a camelhair coat, looking very mirthful and humble. Which, I’m told, he was. I prop up the picture on my desk and look at Taglioni one last time before calling my wife, a psychotherapist. ‘What would mental-health professionals call it if a man has a 30-year infatuation with a machine?’ I ask.

“‘An obsession,’ she says.”

Our own Peter Egan has the affliction, too. At various times the title-holder of everything from 900SS models (old and not-so) to a sleek new 996, Peter met Taglioni by accident:

“When I was in Italy a few years ago for a Lotus tour of the Alps, we stopped at the Borgo Panigale factory for a tour. Our small group turned a corner, and there was the retired Dr. Taglioni, standing in the corridor and chatting with a couple of other Ducati engineers. At the risk of sounding sacrilegious, it was almost like touring the Vatican and finding God standing in the hallway. The great force behind the clockwork of this small, specific universe.

“Dr. T. was thin and somewhat fraillooking, dressed in a gray business suit, and he shook hands with all the visitors in our group, smiling kindly and nodding his head in courtly fashion. We all said buon giorno to each other and then moved on.

“That was it; my one brief meeting with the man behind the Ducati desmo legend. I don’t speak much Italian and he didn’t attempt any English, but I don’t know what we would have said anyway, even with fluency in a common language. Taglioni has spoken through his machines, and I have spoken back, as so many others have, by buying and riding them, or just cheering them on at the racetrack. This is my favorite kind of dialogue, a language that outlives us all.”

Rest well, Ingegnere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue