Up on the roof

TDC

Kevin Cameron

As LONG AS THERE HAVE BEEN RUBBER tires, the hardness of tread rubber has been an important variable. In pavement tires, tread rubber must be soft enough to take a full impression of the road surface, ensuring maximum engagement and grip. At the same time, the rubber must have high tensile strength and tear resistance. That keeps the part that’s gripping the road from being torn off the tire tread.

On hard dirt, softness has value, but on a loose surface, the tire’s ability to keep its tread-block edges sharp despite abrasion can be even more important. That strange genius-engineer-rider of the late 1950s and early ’60s, Albert Gunter, discovered by experiment that prewar Firestones kept their edges better than new Pirellis. Therefore when on his travels he’d roll into a new town, he’d go straight to the Harley dealer and ask if they still had any old tires in stock. If the dealer had some, Gunter would buy them.

That couldn’t last, because in crisscrossing the nation on the way to and from dirt-track races, Al and his friends eventually found all those hard old tires. Now what?

If age made tires work better on dirt, could there be a way to age tires artificially and quickly? It’s not clear here just who invented what, but two methods soon developed: the “roof method” and tire-baking. A few weeks in the sun on a hot Southern California roof, with a few turnings-over in the process, produced a tire that would hold sharp tread-block edges usefully longer than would a new tire. If you didn’t have the time, tuner Erv Kanemoto remembers, there was a man in Gardena who would sell you oven-baked tires. Either of these methods could give longerlasting traction, especially on the loose surface of the old Ascot half-mile.

As so often in life, there was a penalty for impatience. The baked tires would occasionally blister the first time you used them, whereas the “roofed” tires were more reliable.

Blistering needs some explanation. When tire-tread rubber is compounded, about 30 percent of it is a mixture of oils and/or waxes. These become part of the rubber in the mixing process, helping to make it soft and mobile. When these components are cold, their viscosity is high and the

rubber is stiff—it lacks softness. This is the cause of the poor traction of roadrace tires when they are cold, or on the side less used on a given track. If the rubber gets too hot in use, the most volatile of these oils can turn to gas and form bubbles within the tread rubber. This causes a kind of “measles” or bumps on the tire’s surface, leading to vibration and eventual dangerous loss of rubber from the tread.

In normal use, or when a dirt-track tire was “roofed,” the volatile oil turns to gas very gradually. It then diffuses through the tread rubber to the surface and evaporates, or as the Bridgestone people say, “outgasses.” This outgassing, because it slowly reduces the amount of softening oil in the tread, likewise causes the hardness of the rubber to increase. This, therefore, is a major part of why “roofed” tires worked so well.

Baking, on the other hand, was an attempt to hurry this process along. In the case of those baked tires that failed prematurely, it may be that micro-sized bubbles of evaporating softener oil were formed in the tread, generating the beginnings of tiny internal tears in the rubber. Once the tire got hot in racing use, this process of forming bubbles inside the rubber had a head start and might then proceed too quickly, leading to blistering.

Nothing is that simple. Tire engineers learned long ago that pavement grip-especially wet grip-is increased by not fully curing the tread rubber. Curing is

the process by which the plastic raw rubber is transformed, or vulcanized, into a tough elastic solid. This is done by cross-linking the long-chain rubber molecules together by sulfur bonds, a process driven by heat as tires are cured in hot production molds. If the cure is not quite completed in the mold, it can resume when the tire gets hot in use. The reaction proceeds faster the hotter the rubber is made. This post-curing can cause racing rubber to become harder as it is used.

Both of these mechanisms of hardness growth-outgassing and post-curing-are irreversible. A tire that has hardened through exposure to heat cannot recover its former softness and grip once it cools off. This is why roadrace tires are changed so often, and the takeoffs usually show almost no wear. Having been hot on the track, they have lost enough of their desirable original grippy softness to have become useless as race tools-though many a crew chief has supplemented his income by selling the discards off the back of the transporter to willing street riders in search of bargain rubber.

In drag-racing magazines you see ads for tire-softening compounds, to be painted onto tires with the idea of increasing grip by increasing softness. These are liquids that diffuse into the tread to increase the mobility of the rubber molecules. Those who try to harden or soften tires in these ways must follow their experience and common sense.

To make the first laps of roadrace practice or the race itself safer, tires are now pre-heated by wrapping electric tire heaters around them. Even though the heat distribution produced by the heaters differs from that resulting from track use, a hot tire grips sooner and more surely than does a cold one. Before the use of these heaters, the first laps of roadraces were super-tricky contests of judgment versus impatience, and there were many falls. The use of pre-heated tires also saves practice time.

Left in their heaters too long, or at too high a temperature, race tires behave just like those long-ago dirt-track tires up on the roof. They outgas and slowly gain hardness, potentially losing grip in the process. Race tires are like spring flowers-enjoy them at their prime, because once they fade they’re gone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

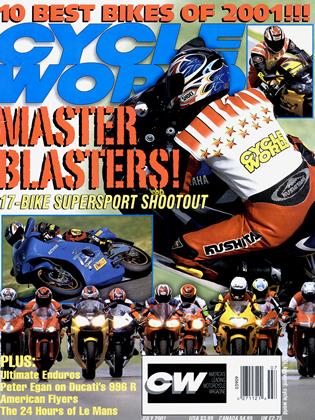

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2001

July 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe World's Most Famous Bike?

July 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

July 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupExcelsior-Henderson Gone Forever?

July 2001 By Terry Fiedler, Tony Kennedy -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Retro Big-Bangers

July 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSauber Surprise

July 2001 By Kevin Cameron