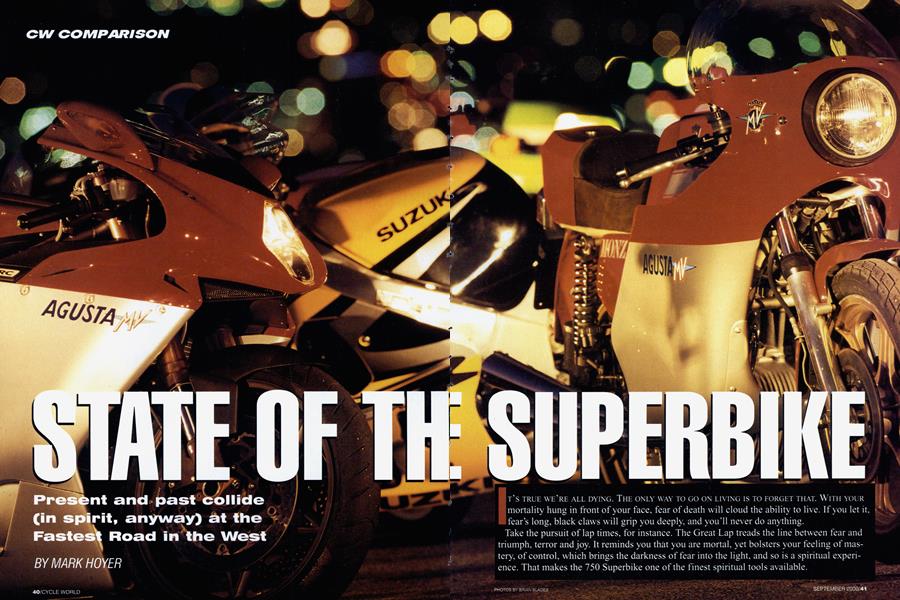

STATE OF THE SUPERBIKE

CW COMPARISON

Present and past collide (in spirit, anyway) at the Fastest Road in the West

MARK HOYER

IT’S TRUE WE’RE ALL DYING. THE ONLY WAY TO GO ON LIVING IS TO FORGET THAT. WITH YOUR mortality hung in front of your face, fear of death will cloud the ability to live. If you let it, fear’s long, black claws will grip you deeply, and you’ll never do anything.

Take the pursuit of lap times, for instance. The Great Lap treads the line between fear and triumph, terror and joy. It reminds you that you are mortal, yet bolsters your feeling of mastery, of control, which brings the darkness of fear into the light, and so is a spiritual experience. That makes the 750 Superbike one of the finest spiritual tools available.

It is itself a device of bal ance, a machine of the fíne line. It lives somewhere between big bikes and small, pulling the highest virtues of both into a package that ultimately exceeds the ability of either across the broadest spectrum of performance. The 750

Supèrbike is frighteningly fast, yet reassuringly competent and manageable at the same time.

As I’ve suggested, though, riding fast is difficult, and crashing has its consequences; the rarity and value of the bikes assembled for this test-four old and four new-made those consequences higher. You wouldn’t want to wreck somebody’s highly valued spiritual tool, would you?

I don’t have to tell you what kind of gravity that lends the whole situation. At least beneath all this heavy-duty Big Question stuff, all the fear, the mortality, the spiritual progress (or its demise), there was always this: Motorcycles are fun. And fast motorcycles are funner.

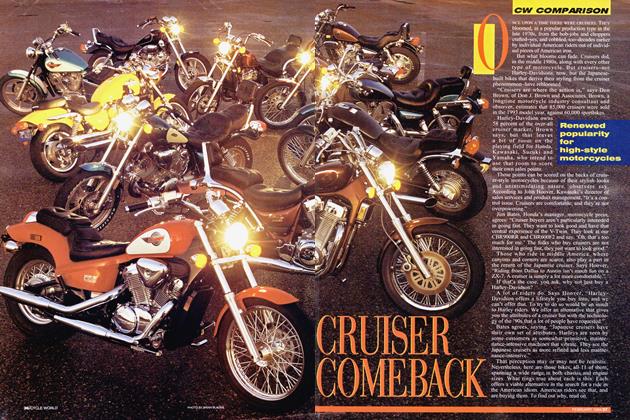

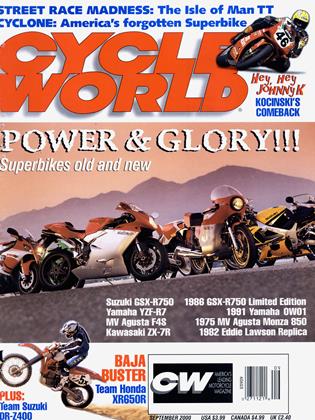

Which is one of the main reasons we put together this comparison of current 750cc Superbikes, with the delicious history of the inline-Four Superbike-750 to 1000cc-laid bare by the historic background music of the progenitors of the class. These four old bikes-1975 MV Agusta 850 Monza, 1982 Kawasaki KZ1000R, 1986 Suzuki GSX-R750 Limited Edition and 1991 Yamaha OWOl-represent their respective eras, each a distinct generation of the Superbike for the street. All are machines to which we owe much of modem sportbiking’s fabulous innovations and the ever-quicker path toward the Perfect Lap.

Where we are in the state of the Superbike is represented by some pretty insanely good pieces of road-going hardware. Seems like we’ve been waiting for the new MV Agusta F4 for the better part of a decade. In fact, it’s been almost that long since the first rumors bubbled up about the inline-Four from Varese. Well, here it is, in $19,000 Strada form, for the first time on magazine test in America, up against the rest on a racetrack.

Likewise for the $32,000 Yamaha YZF-R7, graciously lent to us by a well-meaning and extremely trusting Private Citizen. More rare and 40 percent more expensive even than the F4 Strada, the way-wicked R7 lit Road Test Editor Don Canet’s fire at its initial press launch in Spain more than a year ago, and the rest of us have been dying to lay on the heavy flog ever since.

We’ve all had a chance to sample Suzuki’s new GSXR750. While other companies build limited-production homologation specials that make your heart ache with desire and your empty checkbook weep, Suzuki’s been building the Superbike for Everyman since inventing the superlight beast in 1985 with that first GSX-R. The latest version is no different, except that it’s lighter and more powerful than ever, and so good that it had already taken Best Superbike honors in our annual Ten Best Bikes balloting. Only it took those votes in the absence of an Agusta F4, which wasn’t available for testing in time to be nominated. Here’s your chance now, MV!

Last is Kawasaki’s ZX7R. With us in its current fomi for five years now, the Green Machine is showing its age, although with the proper tweaking it still runs at the front on the AMA National and World Superbike stage. Would it have what it takes in the face of all this radical stuff? Would we?

There really is no place better for an eight-bike sphincter seat-foam tasting than Willow Springs International Raceway, with its famously fast Turn 8 and 9 combo, the hundred-and-too-much-mph right-hand sweepers that are themselves a true study of terror and joy. Blow one of those comers at speed and you’ll be so deep into the desert it’ll take a roll chart to find your way back to the track.

Following several hours of an insane ritual mating dance with the tire-changing machine, our four Superbikes were dressed in some of the latest rubber fashion, Michelin Pilot

Race tires. We won’t spoon-feed you any of that road-test pablum about “testing the chassis, not the tires, blah, blah.”

While to some degree that is tme, these are Superbikes, Willow is a racetrack. We needed traction.

Plus, it was about 105 degrees ambient, and track temp was pushing 140. We needed rubber that could take the heat.

Held up better than us, in fact. Canet would come in after going for times on one of the bikes and be redder than my overcooked pet lobster, Beelzebub. Upon seeing him I said, “I’m going to head over to the snack bar to take a dip in the fryer. I think it might cool me off a bit. Wanna come with?” He chuckled weakly, then stuck his head back in the ice chest. The heat was getting to everybody, including me. Especially after I popped the zipper that joins the top and bottom of my twopiece leathers, which happened just as I was suiting up for photos. When I hunched over, the jacket and pants gaped apart-plumber-butt on an MV Agusta just wasn’t going to do. I solved the problem by sewing the zipper together with safety wire, prompting this comment from the gallery: “Hey, you’re kind of like a fat McGyver, but not as clever.”

It had been a long, risky, hot, hot day in our search for answers, mnning around and around trying to shed light on those dark places. Riding had been a study in contrasts, not only for the eight bikes-new vs. new and old vs. new-but for the two principal riders, Canet and me. For most of us, our limit at the racetrack resides in our brain (that’s me!). For others, people like Canet, the greater limitation is from external factors, such as the motorcycle or its tires. He weighs risks and interprets feedback many of us will never know about. There’s a level of naturalness in his riding, an intrinsic familiarity with motorcycle behavior at extreme speed that long ago displaced the natural panic responses with which most of us are saddled.

Which is what made lapping the old MV 850 Monza such a humorous, contradictory exercise. This blessed job gives me the incredible opportunity to ride the best sportbikes in the world, as this story illustrates. This makes my perceived safe entry velocity for Turn 8 much higher than what is actually safe on somebody else’s pristine, 25-year-old, $35,000 MV Agusta.

So I follow Canet, who’s cruising on the new MV F4, with my brain lying in a hammock, having a rest and listening to this four-pipe Agusta music. We were going slow, see. Except we weren’t, at least not according to the Monza’s old chassis. It wallowed like a sow and headed for the outside of the turn. “Maybe I can get a new fairing from JC Whitney,”

I thought. Me and mortality had a quick look at each other and thankfully went our separate ways. Everything was okay. And actually, after cranking some preload into those old Marzocchi rear shocks, the ride stabilized considerably. It became fun.

The old 850 Monza is an odd motorcycle. For while MV Agusta built some of the most incredible racebikes ever, its streetbikes were less loved, and far from being racebikes. The four-cylinder 600 the company introduced in the late Sixties met with faint praise in CW s contemporary test, and the 750

Four tested in August of ’71 was met with a similar attitude. Still, the contradictions of this bike are wonderful and entertaining in retrospect. The gorgeous sand-cast engine cases and widely splayed camboxes, the large red-and-silver full fairing (a streetbike rarity for its day) say racebike. But these elements are allied with shaft drive and tiny 26mm Dell’Orto carburetors, hardly performance items, even at the time. The styling, however, is wonderful, with an interesting interplay between creases and curves. And the brown suede seat is it. Perhaps the most humorous item on the bike is the huge, V-belt-driven generator/starter tucked under the back of the engine. Yes, it’s both, although it is a much better generator. I tried to start the bike, but it didn’t seem like much was happening when I hit the button. Trevor Dunne, former racer and owner of Dyno Cycle who restored the bike for owner Guy Webster, came over to lend a hand. “You have to let it make the milkshake,” he said.

“Huh?”

He then pushed the starter button. Nothing for a moment, then a faint churning, then a wheerow and a pop. The ancient MV was alive. You just have to let it make the milkshake.

Out on the track, the old Brembo discs were surprisingly good, and tucking in behind that big fairing was a wonderful way to play out all my old dreams of being Agostini. The only thing missing was the super-high redline and open megaphone exhausts. And maybe a dash of riding talent. Anyway, that 850 sounds good through its four chrome pipes, but the old powerplant only revs to 8500 rpm, and, out of respect, we didn’t even flirt with that.

The new F4, however, is all about redline. In fact, at 8500 rpm, the engine’s hardly awake. Power is a little soft on the bottom and hard on top, but fairly slow-revving through it all. Canet concurred, saying, “With the heavy flywheel effect, I have to crack the throttle sooner than anything else, and it’s imperative to keep the revs above 10,000.” Doing so means you’ve got about 3000 usable rpm to work with before the rev-limiter hits, which is just enough, though it’s not quite as nice as the GSX-R, which pulls hard from 9000 all the way to 14,000 and beyond. Engine performance is far from mediocre, though, and as we get more miles on the F4, horsepower is creeping up. This time it managed 111 bhp, vs. the 109 it turned in last month when we first got the bike (see “Strange Company Loose on the Road,” CW, August).

In the dynamic sense, what really sets the MV apart is the chassis. “It’s a 750 Four that thinks it’s a Twin,” said Canet. “There’s a lot of flywheel effect so the power is really tractable. And it has an incredibly narrow feel.” Around Willow, the MV is subtly swift, performing the same kind of deceptive velocity dance that the 996 Ducati has in the past. And still does. Canet came in raving about the chassis. “It’s like a Ducati at its very best.

Totally planted, stable and easy to steer. It’s my favorite in terms of chassis feedback, the front end in particular. Bumps just don’t upset this thing. I can carry more speed approaching the apex, and I’m on the gas sooner than anything.”

The only problem we had was with the MV’s brakes.

Because of its oversized front axle and single-sided swingarm, we farmed out the MV tire change since our in-shop tire balancer wouldn’t work. We later discovered the front end wasn’t reassembled properly, and this adversely affected the brakes. The net result was that they overheated and the lever went soft. Canet felt this handicap added about a second to his best lap time of 1:29.3. Later rectified and system bled, the MV shows no signs of a soft lever. No fault of the bike-otherwise, it was racetrack brilliance.

Of course, what really, really sets the MV apart is its look. Riding the F4 is like wearing a costume, but in a good way. It hums beauty at a standstill and screams it in motion. And, those quad outlet pipes that poke out from under the tailsection and add their own element to the style also mean there are no ground-clearance issues. In the end, the MV makes other bikes look like lumps of cheese and makes you say “YZF-R-What? Hell with cat-eyes!” The MV wears the new face of the Superbike.

If you’re looking for the old face, look no farther than the Kawasaki ZX-7R. As we milled around in Willow’s cell block-style pit garage, Dunne pointed to the badge on the side of the ZX-7R’s frame that said “Kawasaki Heavy Industries,” and smiled, saying, “They aren’t kidding!” He’s right. The ZX-7R weighed 498 pounds without gas, fully 100 pounds heavier than the GSX-R and about 50 pounds heavier than the MV (the R7 was closest to the GSX-R at 416). It also made the least power, some 10 ponies down on the MV, lazily churning out 100 bhp. Runs out of revs just about time it should be pulling hard toward redline.

The bike wasn’t without its virtues, however. Foremost is chassis stability. While it wasn’t really unwilling to change lines, it protested a bit, like it was saying, “Aw, do we have to...?" Which is actually1!.. reassuring in Willow’s high-speed sweepers. Braking power was never in question, with a consistent feel and zero fade, even in the Mojave heat.

When Canet went out for hot laps, he also praised the stability, but was ever-concerned about ground clearance-the ZX had decked its exhaust canister early and often during previous sessions. We jacked the rear ride height (an adjustment independent of spring preload on the Kawasaki) and it gave him more room to play. But at the end of the day, the 7R was slowest around the track with a best time of 1:32.11, nearly 5 seconds off the GSX-R’s best. Everything just happens at a slower pace on the ZX-7, which in many ways makes it the bike that feels most like harmless fun on the track. It also fit my 6-foot-2-inch frame best of the four new bikes.

It wasn’t, however, nearly as spacious as its Superbike grandpa, the KZ1000R Eddie Lawson Replica lent to us by Kawasaki’s John Hoover. In an October, 1982, test, we said the black handlebars were “low,” and there was “enormous” cornering clearance.

Eighteen years later, with hard old tires, we didn’t think testing the cornering clearance was too wise, but the bars?

Those things are like apehangers! Well, not really, but they’re hardly low by today’s standards.

In riding, the 1000R feels immense and super-comfortable compared to everything else in the group, including the MV 850, which is not small itself. The 19-inch front wheel is way out in front of you like a giant fin (rake is a lazy 27.5 degrees and wheelbase is 60.6 inches). The 998cc engine-with a great sound from the factory-fitted Kerker 4-into-l-is nicely torquey, although by today’s Standards it feels pretty slow. This old ELR would make a good Standard bike today. Oh, wait, it does, reborn in the form of the ZRX1100.

The experience of climbing on top of the 1991 Yamaha OWOl was totally different than what it had been on the KZ. My first reaction, though, was, “How quaint.” Canef s feelings were similar: “I feel like I’m at an AHRMA vintage race event.” The seat feels a little low, the trick aluminum tank bulbous and high, with a flat top. What really gives the bike an old feel is the large and high fiberglass fairing and windscreen. It seems like an AJS Porcupine or something of that ilk.

Not surprisingly, this newest of the old felt the most like a proper racebike. Engine power and throttle response were excellent (carbs had been rejetted to suit the added-on factory Superbike silencer). After a somewhat soft bottom-end, the powerband opened for business in the midrange and grew from there. The OWOl had enough pull to make the stretch after Turn 6 down toward Turn 8 a deceptively quick trip. Bend into 8, keeping in mind the bike is owned by an actual human being (our own Nick Ienatsch), not some faceless corporation, and you get a taste of some seriously highquality damping. The fork and shock both are very supple and controlled, and the steering is neutral and light. It’s a pleasure to ride, really. It should be. The OWOl cost $16,000 when it was released in 1990, and you had to have a proper racer’s résumé to lay your hands on one of the few that were brought to the States that year.

Which is quite a similar scenario to how you might posses the bike’s successor, the YZF-R7, a.k.a. the OW02. You still need the résumé, but you’ll need (or would have needed if you’d gotten one of the now-sold-out lot brought to the U.S.) exactly double what the 01 ran you. What’s $32 grand for a little exclusivity? The bike’s gracious owner, Bruce Mills, thought it was worth it. Mills, 46, came late into motorcycling, but you have to give him credit for doing it with such style. After a couple of Honda VFRs (still has an 800) and a VTR1000, he decided it was time for something a little more unique. Of the extravagant purchase, he said,

“It was definitely a midlife-crisis kind of deal; it was either a mistress or a motorcycle. My wife voted motorcycle,” he said with a smile. “Besides, I’ve worked my ass off for 20 years and had some success. I deserved an R7!”

Of the bikes here, this one drips the trickest hardware. Its look is not one of elegance and delicacy like that of the MV, but rather a more pure-racebike look, one of brutal purpose.

A purpose that is revealed in the riding. Canet came in after hot-lapping the R7, and gushed, “That one’s a racebike!” Of course, he had just gotten off the Kawasaki, which probably would have had a hard time keeping up with the old OWOl, much less a current limited-production factory special like the R7.

Still, the R7 was by far the most stimulating bike to ride on the track. The super-taut chassis (Öhlins damping front and rear) is lively without being unstable-it’s a very communicative feel. Gears shift like you’re throwing an electric switch but more positive-it happens so quickly all you hear is a nearly instantaneous change in engine pitch.

On the subject of noise, this has to the best-sounding inline-Four I’ve ever heard, and one of the best-sounding engines ever, period, thanks to the Jardine street-core canister grafted onto the factory header. There are no harsh tones in the exhaust note, just a pure, pitched wail that screams business and soul. You get to hear it all the more so since you’ve got to rev the free-spinning engine to really move. Usable range is 10-14,000 rpm. The other bikes don’t hold a candle to this sound-though a piped GSX-R might come close. Anyway, it’s a magnificent racket.

The 117 ponies of this Stage 1 race-kitted engine (new airbox, different throttle and a magic box that turns on race mode in the electronic brain) are all up top, with a bottom-end and midrange that are very soft. Couple that with tall gearing, and dragstrip testing was an exercise in semi-amusing futility. While it “only” managed a 10.93-second run, the Yam’s 133-mph terminal speed is a testament to how hard the thing pulls once it’s moving. Both the MV and ZX-7R were a tenth slower, but the ZX was fully 10 mph down on trap speed. The MV did an admirable job with its 130 mph. So the R7 is second-fastest in the quarter-mile, yet gets saddled with an “only” qualification? Yep. That’s because Suzuki’s GSX-R750 turned in a phenomenal 10.41-second run at 135 mph! That’s great for any production bike, and unbelievable for a 750. Unbelievable is the overriding theme when it comes to the 2000 GSX-R. But before we visit the new, let’s take a look at its roots.

About the time owner Dave Waugh’s old GSX-R750 Limited Edition was issued in 1986 (the first year the GSXR was available in the states), the only motorcycle I could afford to own (and highside...) was a 1979 Yamaha RD400F Daytona Special. In part of his sales pitch, the former owner of said 400 assured me that, with the right engine work, it would smoke any 750 going. Okay, so I had to crash to find out he was absolutely lying. Yep, those old GSX-Rs were pretty quick in their day. Our testbike at the time weighed 426 pounds without gas and made a claimed 105 horsepower, which at best probably translated to 90 bhp at the rear wheel. As an LE model, Waugh’s bike got the electric anti-dive fork used on the 1100s (regular models had hydraulic systems), a dry clutch, floating rotors at the front and a solo seat at the rear. Price was $6499, a substantial $2100 more than the standard Gixxer of the time. The bike pictured here had been fitted with a rack of bell-mouthequipped Mikuni flatslides, which didn’t help throttle response one bit. It was either all off or all on. And off throttle, the bike would stand straight up in comers. Admittedly we didn’t push the old boy, but even so, the front end chattered like crazy. The tires had hardened to the point that I think my old Big Wheel had better traction. Still, it was pretty cool to ride, and the brakes were excellent. From the pilot’s seat, the inside of the fairing was more unfinished than I remembered, and the seating position didn't seem as bad as it had been made out to be back in ’86.1 also recalled how trick we thought it was that the gauges were suspended in foam. Over the long-term, it appears this might not have been the best idea. Our bike’s foam piece was pretty misshapen, and looked like it had shmnken a bit. Made you want to splash water on it to see if it would swell back to its original shape, like a dried sponge.

The old bike’s specs were surprisingly tme to the new bike’s. In the same way the original GSX-R made our jaws drop at its lightness and ability to rip around a racetrack, so the new 750 does. For while there are now many production sportbikes that come close to the magic 400-pound mark, none have squeaked below-398 without gas ¡-like the GSX-R. And no production bike gets around a racetrack with the same fervency. Lightness helps the bike do what it does in every respect, and allied with the horsepower on tap, this bike outperformed everything in this test. “The GSX-R is in a different class entirely,” said Canet after turning in the fastest lap of the day. “Of all the bikes, this was the one that took no adapting. You just get on and go.”

The odd thing was how comfortable the bike felt. Plush and cushy from the suspension to the seat. It was almost touring bike-like, at least in this hard-edged group. I’ll leave the riding impression to Canet: “It’s odd because the suspension feels soft and compliant when you ride slowly. I thought when I upped the pace it would be too soft. But it just came into its own the harder I pushed. It’s remarkable-incredibly balanced and easy steering. Only negative is that it gives a little twitch once in a while. But everything did that once or twice except the Kawasaki.”

It also had the most phenomenal engine, with the broadest power spread and highest output. On the dyno this time around, it made 119 bhp, 5 ponies less than our first reading, but still tops in this group. And delivery of all this fury was broad enough that you could let the revs drop to 9000 and it would still pull with enough authority that you’d have to be mindful of rear wheel traction on comer exits. This all added up to a lap time of 1:27.38, some 1.5 seconds quicker than the R7’s 1:28.97, which in tum was just .3-second quicker than the brake-hampered MV. Canet said the relative disposability factor of the GSX-R-mass-produced and inexpensive-might have aided his time a bit! Still, it’s a smokin’ lap.

On top of all this, the GSX-R ripped off a two-way average top speed of 168 mph, easily bettering the R7’s 163, the MV’s 161 and the pokey 7R’s 154. It’s an amazing Superbike for the street and track.

In recent years you may have gotten the idea that the only motorcycles with any spiritual character are V-Twins. Can’t blame you, really. We go on about it all the time. With bikes as good as the Ducati 996 and Aprilia RSV Mille, it’s hard not to gush. Yes, big Twins do have their spirit, and they’re bloody fast around racetracks, too. During all this, the 750cc inline-Four has fallen into a weird neglect, stuck as it is between hot-selling 600s and 900s in many manufacturers’ lineups. This has caused Kawasaki to ignore its ZX-7R for years (expect a new one in 2002). And while Yamaha and MV build beautiful and fast limited-production motorcycles that everyone wants, few can afford to buy them. Even Honda, long a lover of cylinders multi, hacked a pair of lungs off its RC45, and through some kind of whacked HRC math came up with 51, a booming, affordable lOOOcc VTwin that sprinted out of the gate in Superbike racing and hasn’t slowed since.

And yet, the classic four-cylinder Superbike continues, flourishes even, that supposedly soulless drone, that torqueless, peaky, hard-to-ride appliance keeps hanging tough and giving those overdisplaced stump-puller cmiser motors a buzz in their ear that just won’t go away. As this test demonstrated, the inline-Four is as rich with history and soul as any Twin-the Four is a formula that works. None better than the GSX-R750. It is the consummate tool for speed, in a class of its own by a wide margin. Amazing that the true path toward the Perfect Lap can cost so little—$9399—and deliver so much. It’s the kind of bike that makes you feel invincible. The only people the GSX-R750 should put the fear of death into is the competition. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMr. Bonneville

September 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafé Americano

September 2000 By Peter Egan -

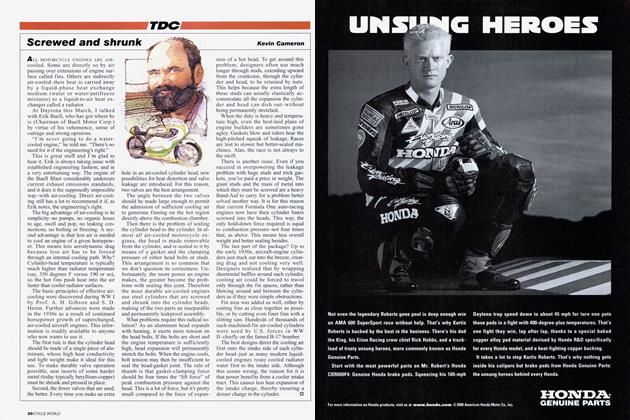

TDC

TDCScrewed And Shrunk

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2000 -

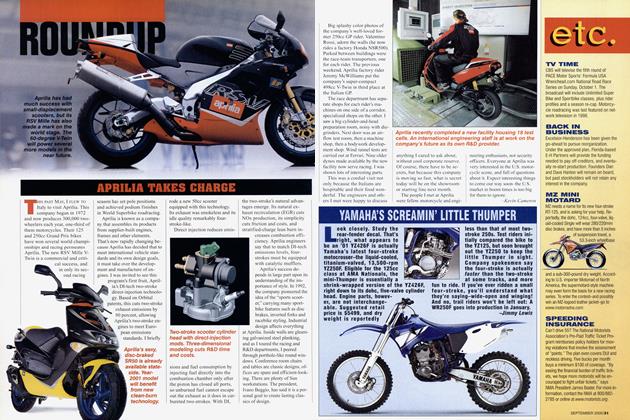

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Takes Charge

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Screamin' Little Thumper

September 2000 By Jimmy Lewis