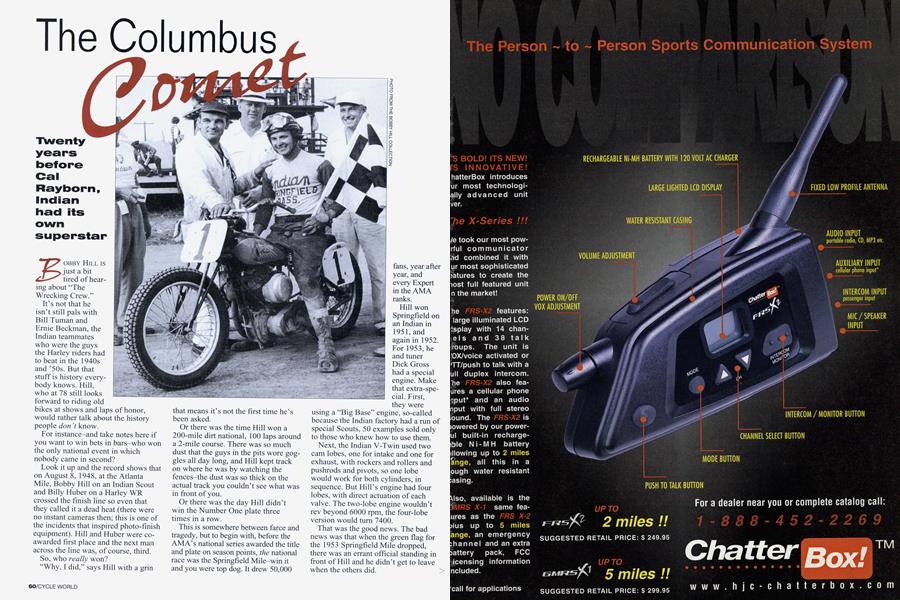

The Columbus Comet

Twenty years before Cal Rayborn, Indian had its own superstar

BOBBY HILL IS just a bit tired of hearing about “The Wrecking Crew.”

It’s not that he isn’t still pals with Bill Turman and Ernie Beckman, the Indian teammates who were the guys the Harley riders had to beat in the 1940s and ’50s. But that stuff is history everybody knows. Hill, who at 78 still looks forward to riding old bikes at shows and laps of honor, would rather talk about the history people don 7 know.

For instance-and take notes here if you want to win bets in bars-who woi the only national event in which nobody came in second?

Look it up and the record shows tha on August 8, 1948, at the Atlanta Mile, Bobby Hill on an Indian Scout and Billy Huber on a Harley WR crossed the finish line so even that they called it a dead heat (there were no instant cameras then; this is one of the incidents that inspired photo-finisl equipment). Hill and Huber were coawarded first place and the next man across the line was, of course, third.

So, who really won?

“Why, I did,” says Hill with a grin that means it’s not the first time he’s been asked.

Or there was the time Hill won a 200-mile dirt national, 100 laps around a 2-mile course. There was so much dust that the guys in the pits wore goggles all day long, and Hill kept track on where he was by watching the fences-the dust was so thick on the actual track you couldn’t see what was in front of you.

Or there was the day Hill didn’t win the Number One plate three times in a row.

This is somewhere between farce and tragedy, but to begin with, before the AMA’s national series awarded the title and plate on season points, the national race was the Springfield Mile-win it and you were top dog. It drew 50,000 fans, year after year, and every Expert in the AMA ranks. Hill won Springfield on an Indian in 1951,and again in 1952. For 1953,he and tuner Dick Gross had a special engine. Make that extra-special. First, they were using a “Big Base” engine, so-called because the Indian factory had a run of special Scouts, 50 examples sold only to those who knew how to use them.

Next, the Indian V-Twin used two cam lobes, one for intake and one for exhaust, with rockers and rollers and pushrods and pivots, so one lobe would work for both cylinders, in sequence. But Hill’s engine had four lobes, with direct actuation of each valve. The two-lobe engine wouldn’t rev beyond 6000 rpm, the four-lobe version would turn 7400.

That was the good news. The bad news was that when the green flag for the 1953 Springfield Mile dropped, there was an errant official standing in front of Hill and he didn’t get to leave when the others did.

The crowd went wild. Hill passed nine guys before the first turn anyway-no question this was one fast Indian-but out of fairness to Hill the race was stopped, then restarted.

Between starts, tuner Gross noticed that the valve in the oil-feed line, the one that kept the crankcase from filling when the bike was parked, hadn’t been turned on. He did so.

Too late. The damage had been done. Hill took the lead on the second start, walked away from the field and had a quarter-mile cushion when the engine went bang.

If it was any consolation, besides Springfield, Hill had a pretty good year in ’53. He won 44 races, came in second 10 times and was third three times. Forty-four wins! In one season?!

Yes, and that’s one way to illustrate just how different things were back then. But we can begin with something that’s never changed. Hill and his brother liked motorcycles. They lived in West Virginia, there was a local club, and the club had events like TTs and field meets.

Mom Hill cashed in a life-insurance policy and bought the boys a Harley WLD, the sporting 45-incher. That was in 1938, and 16-year-old Bobby turned out to be a natural. So the next year they got a WLDR, the raceequipped Harley 45, and began traveling out of the neighborhood and across the river to Ohio, a hotbed of racing (which is one reason the AMA has always been headquartered there).

Then came several interventions.

One was, of course, World War II, for which Hill enlisted in the Marines. Next was that when Hill decided he was good enough to ride someone else’s bike, none of the Harley dealers came forward. But there were seven Indian dealers in Ohio, and they offered the help Hill needed.

This was a different era, so different it’s hard to appreciate the changes. But television had just begun to rot our

/The best way to win 44 races in a season is to run in 150 races a year. Which is just what Hill did, working on his own equipment, rotating four Scout engines. collective brain and people actually went to real-life events. There was a track in every locality, so the racers could compete and win and get paid, three or so times each week. The best way to win 44 races in a season is to run in 150 races a year.

Which is what Hill did. The Indian dealers gave him shop space and parts.

He worked on his own equipment, rotating four Scout engines and keeping records. There was no factory paycheck, or transporter, the interstate hadn’t been invented yet, never mind Motel Row or credit cards.

It was a full-time job. In his best racing years, Hill collected $10,000 per season, which doesn’t sound like much in an era of bonus babies, but comes into better focus with the reminder that back then, the late 1940s and early 1950s, $1500 was considered a fair yearly wage for a man with a family.

Another useful break for Hill came as Indian got into financial trouble.

The company had made some serious mistakes, mostly betting all the firm’s working capital on lightweight designs that were new, radical and flawed. The classic Scout was abandoned, but the

parent company had become a distributor for, gasp, English motorcycles. This meant that in a venue where 500cc ohv engines had an advantagesay, Daytona Beach-Hill got a BSA Shooting Star Twin, on which he won in 1954. And because the Dodge City 200 seemed like a venue where

endurance would be useful, he rode a Norton Single there, and won again. In all, he won 12 nationals-eight miles, one roadrace, one 2mile and two halfmiles-this at a time when a season totaled maybe 10 races. His last race came in 1959, when he was fifth at Daytona. The Hills by then had three kids, and figured that was enough racing, so Bobby went to work for Sohio Oil and various subsidiaries, retiring in 1984. (The actual Hill home was in Grove City, Ohio, incidentally, but because the center of the area is Columbus, and because “Grove City Comet” isn’t quite as effective a nickname, Hill was always considered as coming from Columbus.)

Hill fell a lot, he says now, especially when he was learning his trade, and the joke then was he’d hit the ground at least once at every track in Ohio and West Virginia. But his worst injury was a broken leg in 1947, so falling down didn’t slow Hill down.

To close the circle, Hill’s mom, who (don’t forget) cashed in that insurance policy to pay for his first bike, only saw him race once.

“She’d been worried, so she came to a race, watched me make one lap, and went home,” Hill says. “She said there was no point worrying, it looked obvious to her that I knew what I was doing.”

Allan Gridler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCafé Society

December 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOrthopedic Bike

December 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPaying the Price

December 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Goes Green

December 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEnter the Drako?

December 2000 By Brian Catterson