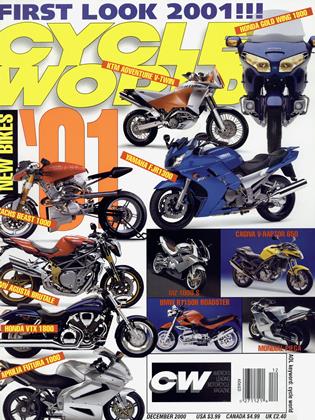

München 2001

The view from the Munich Motorcycle Show

KEVIN CAMERON

IN EFFICIENT EUROPEAN UNION STYLE, THE TURNSTILE ACCEPTS MY press card. There is a click, the rotor turns and I have entered Intermot, the Munich Motorcycle Show. It's huge, filling 11 former aircraft hangars, each measuring 200 x 450 feet, that were once part of Munich’s Riem airport. There’s a new airport on the other side of town and Riem, with opulent refurbishing, has become an exhibition center. Unlike the last show I attended (Cologne, in the early ’90s), there are no bicycles here. Prosperity has made motorcycling strong.

Everything is here. You expect the Big Four to have major displays and they do, but large and small are side-by-side-hole-inthe-wall leathers makers, never-heard-of-it helmet companies, and everyone with a tube bender and fabrication skills is here with gleaming stainless or titanium mufflers and pipes. I know some of the names, like the Australian VeeTwo Ducati modifiers, QUB’s fuel-injection for Yamaha 426 MXers, and even Premier helmets. There are oils, gear companies, chassis-, brakeand wheel-makers-five 400-foot lanes of commerce in every building. Then I catch sight of a large, welllit pavilion offering 15 kinds of Far East scooters with computergenerated names. The brochures are mostly in Chinese. Very young Oriental gentlemen with soft pink hands trot up to exchange business cards. Down the aisle is a tiny white booth displaying cycle parts from the Indian subcontinent, promising yesterday delivery. Its proprietor’s eyes are dulled by jet lag and the passing crowd’s lack of interest.

The first tour takes two hours of steady walking, and it reveals that the most beautiful and attention-getting displays are those of the Italian companies, both the established and the newly reborn. Ducati, Aprilia, Moto Guzzi (revitalized by new owner Aprilia), Cagiva and Benelli are pulling a lot of interest. These early days of the show exclude the public-they are for press and dealers only-but there are plenty of people making the rounds.

BMW’s classy display asserts the brand is about youth and adventure. Do they believe it? I stare at their Cl cabin scooter, with its beautiful leather luggage case strapped on behind.

Kawasaki's show is about to begin. Male and female dancers in hot vinyl outfits are warming up to disco. Up front, four miniature assembly robots dance in lockstep. I'm look ing at the excellent chassis of the ZX-12, which , uses ideas explored in the KR500 GP bike of the early 1980s. When the show starts, it's a precursor for what will follow at the other Big Three-loud James Bond music, smoke generators and not too much in the way of stunning new product. Executives mount the podium and kill any dramatic effect with corporate statistics. They step down and the dancers bounce back, doing handsprings over the bikes, proving that human faces can be sexy yet impersonal. It's a job. This is it. I walk on.

Ducati has a new cylinder head for the 996R and it's very attractive in a glass case, all its parts in motion. Nearby is a turntable with a new 996R and an MH900e. Intense light cascades down on

their extremely bril liant surfaces, making them into wet, deli cious candy. This liq uid color and light make it almost unbearable not to touch and own these perfections. The crowd and I push in toward them. It takes effort to over come their gravity and pull away.

For years I have wondered who would find the engineering courage to match an uptiow exhaust-port angle to the downdraft intakes that are now universal. Twenty years ago, both carbs and pipes flowed at 90 degrees to cylin der centerlines. Exhaust flow is supersonic and heat transfer is tremendous, but exhaust ports have retained their inefficient, heat-gathering 90-degree turn nevertheless. It is Ducati, in the new 996R cylinder head, that has at last given flow and heat transfer precedence over tradition and styling. The new exhausts emerge upward. Bravo. A whole wall of the display is engineering drawings of the new head, magnified. Beauty, engineering, art-inseparable. There’s another facet, though, perhaps just as important. Ducati, by productionizing and redesigning its 996, shows that it (or owners TPG) knows low manufacturing cost is as important to survival as the company’s fall-in-love style has been to its rebirth.

What theme emerges from this show? I see the Japanese ship of state serenely plowing onward through calm seas as if the world will never change. But there is change. The recent prosperity and the growing sophistication of the motorcycle-buying public have combined to bring up green shoots of new growth in many countries. In Italy, Aprilia is a young company (1972) growing rapidly. In buying Moto Guzzi, Aprilia has acquired a way to express important traditions as well as its own ideas. Mondial and Güera are here, both major players of the 1950s. Benelli, once a powerhouse, has come back from neardeath to offer the 900 Tornado, which subtly combines new and old. Tradition is carried forward in the nipped-at-thewaist fairing, suggesting those of the great Benelli racing Fours, and in the traditional silver-and-green paint scheme. The radiator is beneath the seat in Britten/Saxon

Triumph style, fed by ducts from high-pressure areas at the front. Outflow into the low-pressure wake is boosted by a pair of yeilow-bladed electric fans. The triangular (get it?) Arrow muffler pushes style toward a cheesy Buck Rogers look. The top-injected 83.8 x 52.4mm Triple is claimed to make 142 bhp at 11,500, at moderate piston speed and combustion pressure. Long live diversity.

Over in Hall A3, Honda’s radio-controlled model zeppelin glides past overhead. Suzuki’s wide palazzo tells us a little about the light new GSX-R1000, while the company’s hovering colored balloons prevent a Team Red invasion of its airspace.

The Voxan V-Twin occupied an understated display, but revealed important points. Each tubular steel frame beam is also an oil tank, bolting to the cast-aluminum steering head with five Allen screws. Management is feeling for its market. What images will sell this French motorcycle? Audrey Hepburn in Givenchy? Gauloises-smoking Resistance fighters of WWII?

Honda’s news was under covers on a turntable, tarps whisked off, one by one, by six high-energy dancers. I stayed by an NSR500 GP bike where the music was bearable. Aha, a new 1800cc lightweight Gold Wing, with aluminum chassis, radial tires, optional ABS and a leaning tower of streamlined luggage. Take that, BMW! And a PGM-injected CBR600F4L And a big new cruiser. And a 600cc scooter.

I counted 20 makers of scooters and light motorcycles, coming variously from Indonesia (you’ve heard of Modenas), India, Mainland China, Taiwan and elsewhere. New makers or revived old makers are appearing in Spain—Derbi, again strong in 125 GPs, has revived Bultaco. Asian makers begin by buying complete outdated step-through factories from the Big Four. Their engineers study production and emissions. In time, as incomes rise, sportier mounts emerge-125s, 175s, then 250s. These are clumsy-looking, chopper-styled and chromerich now, but they represent change. These people Í are reading our Western magazines very * carefully.

What about style? Are there fresh themes? Japan continues on its established path, but Europe is seeking its own way, working to be differ ent. The combina tion of flat-black paint on many models, with sharp-edged, zigzag planar shapes begs to be called The Stealth Look. Aprilia's Futura 1000, the BeneIli 900 Tre, Cagiva's Raptor and the new Mondial Piega 1000 all share this theme. Dated but still powerful is the curvaceous "organic look" exemplified by the MV Agusta F4 and Ducati 996.

Japan owns the twin-aluminum-beam chassis, but European designers want different identities. Because frames are just the hypotenuse of a triangle of which two sides are formed by the engine and gearbox, they don’t have to resist twist and bending forces unassisted. This means that alternatives can work-Ducati’s trellis, Voxan’s bolted steel tubes, Benelli’s set of four snaking curved tubes socketing into lumpy swingarm uprights.

Moto Guzzi’s Rosso Mandello is a Christmas tree, offering many textures, colors and bright machined-metal highlights in a tasteful, attractive way. I am not a particular fan of the old Mulo Meccanico Guzzi V-Twin, but I can still admire the variety of effects this lately struggling company has achieved around it. Turning from it 180 degrees, I see a towering display of history, pulled from the famed Guzzi museum in Mandello del Lario. At the top is Engineer Carcano’s greatest leap of imagination, the 500cc V8 GP bike of 1957. When I spoke with Aprilia President Ivano Beggio in August, he had said that in time, other classic concepts from Guzzi’s past may be updated to take their place in the product line.

Motorcycle technology is not a secret anymore. Efficient manufacturing is not a secret anymore. Neither are com puters, fuel-injection or suspension technology. These facts mean that even small companies, modestly funded, can create quite ambitious designs. Combined with strong economies that make investment available, this means variety.

A strong example is KTM’s new LC8 one-liter (942cc, actually) 75-degree V-Twin. At their pitch, company personnel wore orange shirts and were a tough, healthy bunch who’d look right in Special Forces uniforms. Despite the informality and enthusiasm of off-road riders, the KTM presentation began with a deadly business review. Claustrophobia found me an exit through the kitchen. When it was safe to return, I met the designer of the new Twin, Claus Holweg. He is an of everything: compact, rigid cases; modern end-feed oiling to the crank; strong, thoroughly analyzed recip parts. All engine accessories-counterbalancer, waterpump electric starter, camchains-are driven by a shaft that resides in the vee of the cylinders. The LC8 is expected to develop rapidly over the next two years beyond its present 102 bhp at 8000 rpm. This, with the engine’s 100 x 60mm bore and stroke, gives a leisurely piston speed of 3150 feet per minute, and a stroke-averaged effective combustion pressure of 175 psi. Compare these with racing figures of 4500-plus piston fpm and 190-200 psi and you see there’s more to come. The engine weighs a minimal 123 pounds.

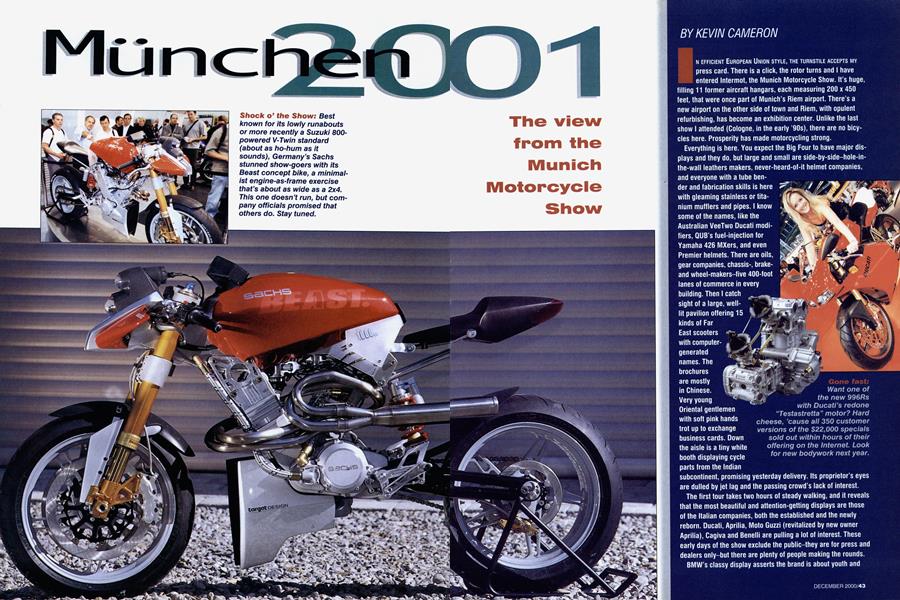

As a pure extreme, consider the Sachs Beast, a one-liter VTwin that’s like a Britten pared to the marrow-two wheels, an engine, a padded prong to sit on. Production? Who knows? Maybe. The Beast was a moistened finger, sampling the wind.

Naked bikes are today’s big phenom. Japan had more of them than of anything else new, and MV’s new Brutale, Ducati’s fourvalve Monster, the Voxan Roadster and others correspond to Yamaha’s new R1-powered Fazer 1000, called the FZ1 in the U.S. We think of 996s when we think of Ducati, but it’s the naked line that pays the bills in Bologna. Why? Some say it’s a retro impulse, and there’s something to this. Eddie Lawson Replicas take us back to the days of power-laden Superbike wobblers barely mastered by hero riders. Intoxicating stuff. But there’s more. Naked bikes combine powerful elements from both cruiser and sportbike. A cruiser is a locomotive, with visible engine and a rider who is astride-not growing into the machine, but above it as master.

Sportbikes concentrate the ballistic attributes of the motorcycle-acceleration, speed, braking and handling-but at the cost of aerodynamic concealment and, therefore, a degree of visual emasculation. Not all riders want to be packaged into a huddle, as North Country English race star John Cooper once put it, “With head doon and oss oop.”

Neo-naked bikes give the rider both. Ballistic power in nearly full measure, with the classic position of command, sitting up, facing fate squarely. I remember a rider who once said, “Never mind the lap times...how’d I look?’

I treasure such contacts as I have in the industrial design world. One I ran onto at this show complained that some bike-makers completely ignore style. Their engineers assume that if they do their work correctly, place the major masses properly, with adequate strength in all parts, the result must by definition be beautiful. This, he pointed out, ignores the fact that engineers and the public “speak” different visual languages. What looks good to the engineer may mean nothing to the public, or even be seen as ugly. With a degree of interpreting from a designer, the accomplishments of the engineers can be made clear to the public.

Motorcycles are a strange combination of fact and fantasy. Yes, quarter-mile times can be measured, and a few buy by the numbers. Others are happy with pure transportation. It’s much more complicated for the rest of us. Motorcycles carry a strong message just as human faces do. In some submerged non-verbal way, they begin to tell us a fascinating story that we can’t resist. There’s no way to know the ending except to become ourselves a part of that story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCafé Society

December 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOrthopedic Bike

December 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPaying the Price

December 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Goes Green

December 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEnter the Drako?

December 2000 By Brian Catterson