SCOOTERWAY TO HEAVEN

RACE WATCH

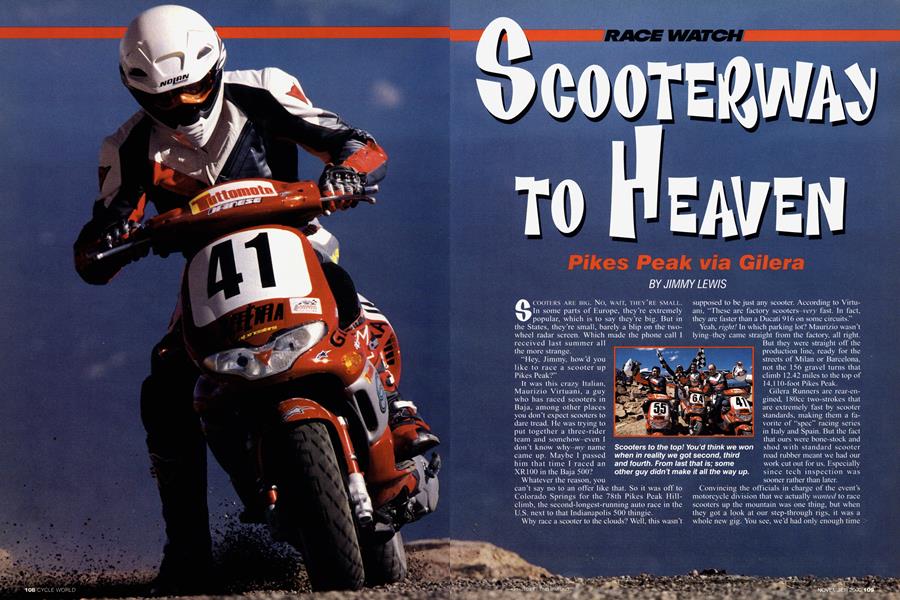

Pikes Peak via Gilera

JIMMY LEWIS

SCOOTERS ARK BIG. No, WAIT, THEY’RE SMALL. In some parts of Europe, they’re extremely popular, which is to say they’re big. But in the States, they’re small, barely a blip on the twowheel radar screen. Which made the phone call I received last summer all the more strange.

“Hey, Jimmy, how’d you like to race a scooter up Pikes Peak?”

It was this crazy Italian, Maurizio Virtuani, a guy who has raced scooters in Baja, among other places you don't expect scooters to dare tread. He was trying to put together a three-rider team and somehow-even I don’t know why-wy name came up. Maybe I passed him that time 1 raced an XR100 in the Baja 500?

Whatever the reason, you can't say no to an offer like that. So it was off to Colorado Springs for the 78th Pikes Peak Hillclimb, the second-longest-running auto race in the U.S. next to that Indianapolis 500 thingie.

Why race a scooter to the clouds? Well, this wasn't supposed to be just any scooter. According to Virtuani, “These are factory scooters-verv fast. In fact, they are faster than a Ducati 016 on some circuits.”

Yeah, right! In which parking lot? Maurizio wasn't lying they came straight from the factory, all right. But they were straight oft' the production line, ready for the streets of Milan or Barcelona, not the 156 gravel turns that climb 12.42 miles to the top of 14,1 10-foot Pikes Peak.

Gilera Runners are rear-engined, 180cc two-strokes that are extremely fast by scooter standards, making them a favorite of “spec” racing series in Italy and Spain. But the fact that ours were bone-stoek and shod with standard scooter road rubber meant we had our work cut out for us. Especially since tech inspection was sooner rather than later.

Convincing the officials in charge of the event’s motorcycle division that we actually wanted to race scooters up the mountain was one thing, but when they got a look at our step-through rigs, it was a whole new gig. You see, we'd had only enough time to slap on the necessary race numbers and a few other stickers to make the bikes legal-testing for race setup was another whole day’s work. Plus, there was this box waiting for us, supposedly full of “special parts,” that we hadn’t even opened yet.

We passed tech by the seat of our pants-or more accurately, the tech inspectors’ pants, because only after the three of them had taken our “racebikes” for a 5-minute spin through the streets of Colorado Springs did they consent. “Yeah, sure, you guys can race these things,” one said with more than a hint of sarcasm in his voice. We later learned that they’d bet we wouldn’t make it to the top in under 20 minutes-if we made it at all.

At 3 a.m. the next morning, we headed to the gate of the Pikes Peak Toll Road for our initial “scoot” up the hill. Practice started at first light with a series of open runs from the midway point of the course to the top of the mountain for two-wheeled vehicles. The four-wheelers, meanwhile, were qualifying on the lower portion of the course. All of this takes place before 9 a.m., when the road opens to the hordes of tourists who flock to the peak to get a view from the clouds (or above), and maybe a famous donut from the coffee shop up there.

When we unloaded at 12,000 feet, I knew I wasn’t going to be the only one short of breath if these little go-peds didn’t make the climb. But I needn't have worried, because with their fast fingers, our two Güera factory technicians threw a bizarre combination of jets into the tiny carbs in a matter of minutes. As a result, all three of us made it to the top on our first attempt. Sure, we were slow, but we made it.

Back in the pits, we compared notes and zeroed-in on the best jetting setup. I, being the rocket scientist that I am, realized that the airbox cover was the biggest obstruction to power. So in the absence of any ability to communicate this to the Italian-speaking mechanics, I took out my trusty saw-blade-equipped pocketknife and fashioned an appropriately sized hole. On the next run, in a side-by-side comparison with the other Runners, my performance mod apparently worked-better and better as we got closer to the top. Horrified by the crudeness of my modification, the Italians shied away from doing the same to their bikes as I tried to make the hole look and perform even better.

The following morning, up again at 3 a.m. for a run on the lower portion of the course, we were greeted by absolutely perfect road conditions thanks to an overnight thunderstorm. “Ego-dirt” is the only way to describe the velcrolike traction we experienced. Even riding scooters-now shod with the roadrace rain tires we found in the special box-this was a day to remember. Riding the bikes at the top the day before had proven they were slow. The bottom only drove the point home further. This assumption was later verified by the SuperFlow dyno in the pits: 12 horsepower at the midway point of the course, and a whopping 13 at the lower-altitude pit at the base.

But as underpowered as our scooters were, the little 14-inch tires made working the turns just as tricky as it was for the fast guys on their fullblown flat-trackers. I’m telling you, we had comer speed. But the straightaways were lessons in drafting. I found the horn to be of great assistance, sometimes confusing Cristian Matte, the “ringer” scooter racer Maurizio brought along with him. Horn usage has an aggressive history in Italy, I’m sure.

So what about this box full of special parts? I never saw the actual contents, but aside from one trick, hand-conedand-weldcd pipe that graced Cristian’s scooter for one run, nothing else but the tires seemed to have fallen out. Apparently, the mechanics were set on having us run to the top on near-standard machines. I’ve seen some pretty trick scooters and heard stories of even faster ones, but ours weren’t those.

Race day had us up again at the same inhuman hour. After all, we had to be ready for our 2 p.m. start time, right? Thousands of spectators piled onto the mountain for the race, many of them camping out at their favorite vantage points. It’s all part of what makes Pikes Peak a “happening,” a history-rich event complemented by the circus parade of machines that run to the top. From a tube-frame, 1000bhp, winged thing that Toyota would have you believe is a “truck”-with which Rod Millen attempted to break the 10-minute barrier-to stockcars, sprint cars, open-wheeled racers and luxury sedans. Even big rigs make the run-full-on over-the-road, diesel tractors less the trailer. And guess where they started? You got it: right behind our 12-bhp scooters! Needless to say, the concern the officials expressed about getting our butts up the mountain was to ensure we wouldn't end up being bumper-bait for a mega-horsepower Mack.

In the absence of a scooter class, we were forced to run with the 250cc Pro motorcycles. You could pretty much guarantee the rest of the field would be out of sight by the first turn! But based on practice times, I was set to have a good race with Cristian. I'd been a second quicker on the top half, and he’d been a second quicker on the bottom. Maurizio, on the third Runner, was a bit more cautious, and so was a few seconds off our pace.

Drier conditions on race day gave the road an all-new face: grip like asphalt on the racing line, and like a marblecovered sheet of glass if you got off. Not the kind of conditions you look forward to when you’re riding the ragged edge of traction-even on a scooter!

As the day wore on, Millen’s Toyota made it halfway up the hill before blowing up, a Japanese driver did a little clear-cut deforesting with his race car, and most of the other drivers went up the mountain hell-bent for speed while we waited for our turn.

The field was set according to practice times, which meant we were gridded at the back, on the third row. One other guy who was penalized for riding down the road too fast after practice had to start alongside us. As we lined up, I glanced down at Cristian’s scooter and noticed that there was a hole in his airbox cover in the same place I’d cut mine. Upon closer inspection, it looked exactly like mine. So much so that I checked the airbox cover on my bike, only to see a cobby half-ass duplication, without the fine airflow craftsmanship I’d taken the better part of 3 minutes to achieve. Whether it was an honest mistake or a dishonest one, Cristian now had my airbox.

The green flag flew, and we were off! Or my Italian friends were, anyway, as I promptly proved that I was no automatic-clutch moped-launching specialist by failing to dog-paddle off the line.

Rolling up the road at a pace that could best be described as possibly surpassing the posted speed limit, we were racing to the clouds. With the slippery conditions, we were pushing the edge of traction, yet even so, we kept it pinned, even in the turns. I developed the technique of braking under full power, using the rear brake to load the engine and then slingshot out of the corners. Of course, at the speed I was going, I should have been tossing out copies of the Pikes Peak Gazette as 1 went!

About five turns into the race, my scooter started spitting coolant from the overflow tank. It must have just been overfilled, because the temperature gauge never got near the red zone. It made the floorboard slippery, though, especially after the rubber mat flew off going into a right-hander. Naturally, my foot flew off along with it, and the sudden loss of pressure on the floorboard thew the chassis into a violent swap heading straight for a roadside ditch. I played desert racer and lifted the front wheel, made a bank-shot and ended up right back on the road. But I’d lost Cristian’s draft.

I hit the halfway campground and gave the Güera a few cowboy whips to see if it had anything more for the radar trap. Guess not: It recorded just 48.6 mph, absolutely tapped. This compared to 83 mph for the class winner and more than 100 mph for the fastest cars.

Cristian and I ran about 2 seconds apart until we hit the 2-mile paved section near the middle of the course. Here, my teammate pulled me big. He obviously had the roadracing gene that I lack, and was leaving big black marks on the road. (No, they weren’t from powerslides.) There was no way I was going to catch him. I proceeded to pop as many wheelies as I could for the fans while honking the horn and waving, all at full speed. But just as I hit the dirt again, I came upon a cloud of dust-Cristian was jumping up to get going again after a crash! I almost made the pass, but with his highly refined dog-paddle start, he bested me again. I used my higher cornering speed in the dirt to try to get past him, but at this altitude “my” airbox was allowing his scooter to pull me on the straights. At least that’s my story...

At the finish line, Cristian beat me by 6 seconds with a total time of 17 minutes, 40 seconds. Don Burner, meanwhile, won our class with a time of 12:52, a new record, beating out the big bikes that had run earlier in the day on a much more slippery course.

Our times weren’t too shabby for a pair of scooters. In fact, we beat a couple of motorcycles and the electricand propane-powered cars that failed to make it to the summit. Most of the so-called “showroom-stock” cars beat us, though. But considering my Gilera was a top box away from delivering pizzas, I’ll take it.

In the end, we didn’t win anything except a ton of laughs and high-fives from spectators as we made our way back down the mountain. But we never expected to win. We just wanted to make it to the top, and in so doing added to the strange brew of vehicles that climbs Pikes Peak in rapid fashion.

Speaking relatively, that is.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGp Four-Strokes

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

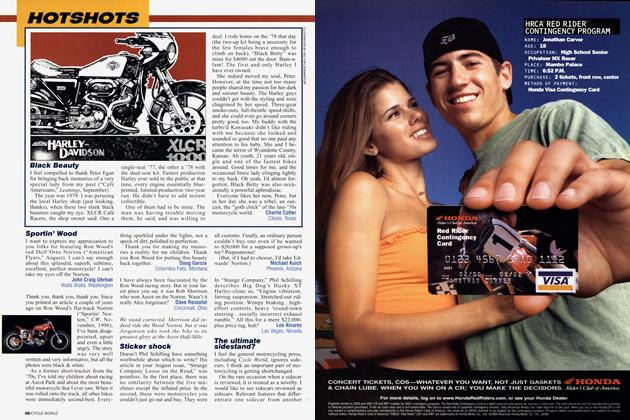

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson