Being Ben Bostrom

RACE WATCH

Watch out, Evel Knievel!

KEVIN CAMERON

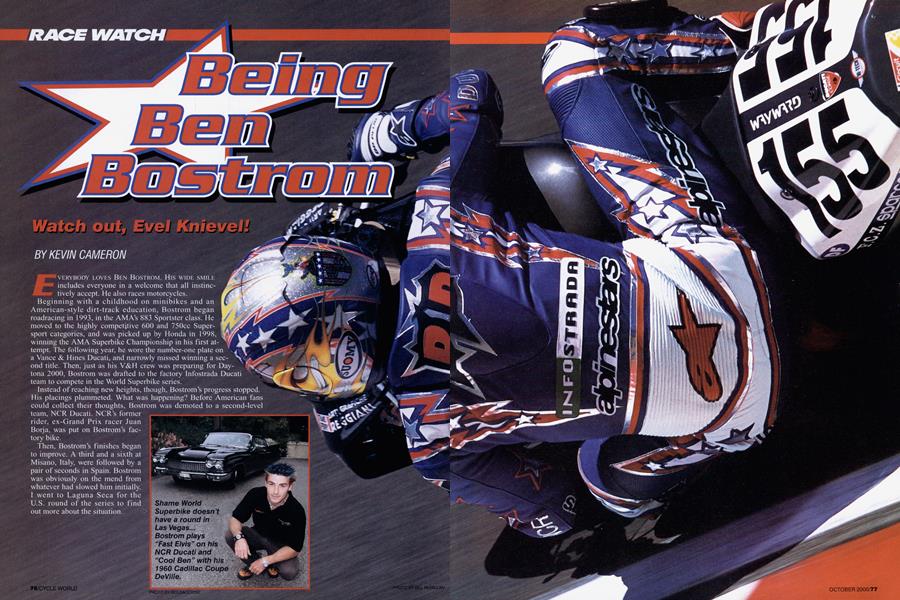

EVERYBODY LOVES BEN BOSTROM. HIS WIDE SMILE includes everyone in a welcome that all instinctively accept. He also races motorcycles. Beginning with a childhood on minibikes and an American-style dirt-track education, Bostrom began roadracing in 1993, in the AMA's 883 Sportster class. He moved to the highly competitive 600 and 750cc Supersport categories, and was picked up by Honda in 1998, y winning the AMA Superbike Championship in his first attempt. The following year, he wore the number-one plate on | T a Vance & Hines Ducati, and narrowly missed winning a second title. Then, just as his V&H crew was preparing for Day* tona 2000, Bostrom was drafted to the factory Infostrada Ducati ^ team to compete in the World Superbike series.

Instead of reaching new heights, though, Bostrom’s progress stopped. His placings plummeted. What was happening? Before American fans could collect their thoughts, Bostrom was demoted to a second-level

team, NCR Ducati. NCR’s former rider, ex-Grand Prix racer Juan Borja, was put on Bostrom’s fac-

Then, Bostrom’s f inishes began Misano, Italy, were followed by a pair of seconds in Spain. Bostrom was obviously on the mend from out more about the situation.

Many people at Laguna were talking about Bostrom-after all, he won race two last year, which was what brought him to the attention of Infostrada Ducati in the first place. Merlyn Plumlee, a mechanic at American Honda, had earlier said to Team Manager Gary Mathers, “You watch what happens now. Ben’s finishes are going to improve. Those guys at NCR actually know more than the (trackside) people at Ducati, and they know

more about riders, too.”

As Bostrom prepared to go out for Saturday practice, he looked happy in an uncomplicated way. I thought at the moment that he looked like a person about to eat his favorite dessert. When practice was over, Bostrom sat down at a-small table in his tent, still in his starspangled Evel Knievel-style leathers. With him were three NCR men and Mark Elder, a mechanic and friend from Bostrom’s V&H days. With visible formality, the five of them went over the day’s developments, passing papers among themselves as if gravely playing a large-format card game. Later that evening, as dusk came on, I sat down with Bostrom for some conversation. He spoke in the same way

I’d seen him spin his Ducati’s rear tire

at the bottom of Laguna’s famous Corkscrew earlier in the day-forthrightly and with confidence,

He explained that there were no bad guys in his story. As outsiders tell it, Bostrom was required to ride Infostrada bikes with ex-Ducati rider (now with Aprilia) Troy Corser’s settings, Elder was kept out of the loop. It was Michelin tires or else. As Bostrom tells it, it’s much less black and white. He’s happy to be with NCR because they are getting results and Elder is back on the team. He is determined to learn to ride Michelins. And when Bostrom requested the settings he’d used at V&H, the Infostrada team changed his bike to suit. “When I tried \hosQ-bang!-'\t was better,” he said. “That was when I began to climb back up, after Sugo, Japan.”

The problem?

“I couldn’t feel the front,” Bostrom explained. “You get into the turn, then you decide you need to tighten your line. You turn the bars a bit more and it steers tighter-it’s okay. If you need to go tighter yet, it may not steer tighter. Instead, the bars ‘cross’ and you’ve lost the front end. If you can’t feel when it’s going to do that, you don’t know how close you are to crashing. I wadded up about seven

bikes. I lost all my confidence.

“When I started with Infostrada, I was serious,” Bostrom continued. “I spent all my time with the bikes, thinking about racing. It was too much. I was feeling down, and it wasn’t any fun. All the fun had gone out of riding. I had to change something. I went out, had some drinks, thought it all out.”

Earlier, WSB tech inspector Steve Whitelock had said to me, “Michelins are hard to switch to, but it’s good Ben has stuck with them. He’s twice as valuable now because of it.”

Whitelock also noted that, at the world level, the number of tire choices is very large. “They open this book, and in there are wide and narrow, V-profile and round, all kinds of constructions and compounds and diameters,” he explained. “You don’t figure it all out the first day. When Ben was ‘sent to the minors,’ he didn’t get the good Michelins anymore. He had to learn to ride standard-issue. Then, when his (improved) times demanded

two good ones, he really went fast.” Whitelock agreed that the move to NCR had been good for Bostrom. “The NCR guys say, ‘Go out, have fun. Racing is supposed to be fun.’ ”

I mentioned to Bostrom that I’d seen him spinning the rear tire to get the bike turned at the bottom of the Corkscrew. “You’re not supposed to spin Michelins like that,” he replied. “But I’m doing it. And it works.”

Ducati is not the bad guy, either. The company gave NCR a $150,000 parts credit for Bostrom’s use, and that has now been doubled.

Last year at Laguna, everyone watching noted how loose Bostrom’s bike appeared, especially during braking. Whitelock explained, “Bostrom’s teaching the Europeans that a bike can be loose and move around, and still be okay. They were all raised on that classic line as the only right way to do it.” Bostrom explained, “I go in. I get the back end out a bit. You don’t want to back it in, because you’ll burn up your tire. (Yamaha’s Noriyuki) Haga backs it in. I bring it back with the footpegs or the bars. Then, I push until it moves again. They say, ‘You’re wobbling around in the turn,’ but that’s my way. That’s the way I do it. And my way is going to prevail.

“If what they gave me were Corser’s settings, then Corser must never change his line in a turn,” Bostrom

continued. “He wants the front end kicked way out there. I want to be able to change my line.”

What does this mean? It is the ageold contrast of styles between a dirttracker, who must use all the traction under his tires, and the classic roadrace

style of carving the curve of maximum constant radius. It is like the contrast between those greats of the 1960s and ’70s, Gary Nixon and Cal Raybom. By pushing the tires to the edge and recovering in a repeating cycle, Bostrom samples the grip under him as he goes-almost analogous to how antilock brakes work in stopping. By riding on a constant radius, the classic rider must limit his corner speed to what the minimum grip on his trajectory allows-not always enough.

After Sunday’s races, Bostrom was asked about his two hectic passes at the top of the Corkscrew: “I knew if I could get up the hill with somebody, for sure I was going to displace him.”

This is another classic dirt-track move, one familiar from Nixon’s pavement career as the “stuff.” You stuff your machine inside your victim as you enter the turn, moving faster.

As you go wide, you force him out as well, off his carefully crafted line. Pushed into the unknown, he lets you by. The rider who feels for grip as he goes can ride any line and go fast. The classic rider knows only the graceful arc of his constant radius.

Bostrom’s parents have been described as “old hippies who believe that a human being has a right to enjoy life.” I mentioned this to Ben. “That’s the way it has to be,” he said. “If you do the thing you’re good at, what you love to do, the money’ll come. You don’t worry about that. You just live and do what you do best.”

He looked down at the table briefly, as if gathering his thoughts. “Here’s my theory of life,” he said, looking up again. “Life is short. You’re gonna die. You don’t know when that is. It could be tomorrow, walking across the street. So that means you have to be sure you’re enjoying every moment right up until then, whenever that is.

“I’m really lucky,” he added. “I have the best life there is, doing what I love to do.”

Fans love Bostrom, approaching him readily, posing for photos as if they were all family guests at a wedding. There is no formality or awkwardness, no sense of time urgency. He banters with well-wishers and signs autographs cheerfully until everyone is gone. Who could ask for anything more? Bostrom is the classic Young Hero. He slays his dragons easily, without angst, without emitting hazardous race-face radiation.

Bostrom’s NCR crew is businesslike. During a routine drive-chain replacement, it was discovered that the rear brake was dragging slightly. At a gesture from a senior man, another mechanic trotted up. With a practiced cadence of pedal and wrench movements, he bled the system until the rear hub again spun freely.

Despite his earlier predictions, Bostrom was not to win either of Sunday’s two races. In the first, he worked his way to second, benefiting from Corser’s fading tire, then was pushed to third when Corser made a last-lap inside pass in the final turn. The race was won by charming wild man Haga, whom the American fans love for his apparent ability to work miracles fueled only by pure energy. Nothing is this simple. In Sunday-morning practice, Haga’s Yamaha was spinning its rear tire over the ripples exiting Turn 11, shrieking its engine to astronomical revs and spoiling his drive. By race time, it was fixed-no more spin.

As a perspective on this problem, consider Mat Mladin’s predicament in Saturday’s AMA National (this was, for the first time, a dual weekend-an AMA National on Saturday and two WSB races on Sunday). Mladin likes his Suzuki to change direction instantly, and stiff suspension is a major ingredient in this. It also causes wheelspin over ripples. After his race-long pursuit of Honda’s Nicky Hayden, Mladin made two desperation passes in Turn 11-neither of which stuck because Hayden got the drive while Mladin spun the tire. Too much of a good thing is still too much.

In the second World Superbike race, Bostrom used the inside stuff to pass both series leader Colin Edwards and Haga on different occasions at the top

of the Corkscrew. Corser, meanwhile, was conserving tires for a late charge that eventually took him to the win. Haga, having overworked his tire early in the race, hung back to rest it.

A last-turn, last-lap move made him second and Bostrom third.

How good is Corser’s Aprilia? Laguna is not a horsepower track, but the Aprilia seemed to have enough of everything-including the ability to lift its front wheel going up the long “dyno” hill to the Corkscrew. Corser told the press after the second race that he had used the same type of tire in both races, but had conserved it for the end in the second. “You win races in the last laps, so that’s where you want the tire to work,” he said. “I can’t wait ’til we get a stronger engine. I was riding the wheels off this thing.”

And so he was, doing what riders of underpowered bikes must always do, starting the turns on the outside dirt, cutting the apex to zero tolerance, and having to pick up suddenly to keep from running off at the exit. “Underpowered” is a relative term-the Honda RC51s of Edwards and Aaron Slight have a lot of steam, but lacked the grip to make it work at Laguna. Each track requires its own balance of qualities. This year’s Aprilia has a bigger airbox with a new frame to suit, twin mufflers instead of a single and obviously reworked valvegear. Last year, it had the loudest valve noise in the paddock. Now, at warm-up revs, the rattling of the straight-cut primary gears is louder than the valves. As one insider pointed

out, the ’99 engine would stop instantly if the throttle was closed. Now, it coasts through several cycles as if idle-speed friction has been greatly reduced. Expect more progress.

At the post-race press briefing, Bostrom was asked if he’d had concerns about sliding tires at the end. “Nah, I love that stuff!” was the cheerful reply. “We’ll come back next year and win both of ’em, for sure.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRally At Red Rocks

October 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsLate-Braking News

October 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaking It Happen

October 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Suzuki's Big-Bore Blaster

October 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupGood-Bye, King of the Roads

October 2000 By Brian Catterson