R32

The World's Oldest Beemer Rides Again

PETER EGAN

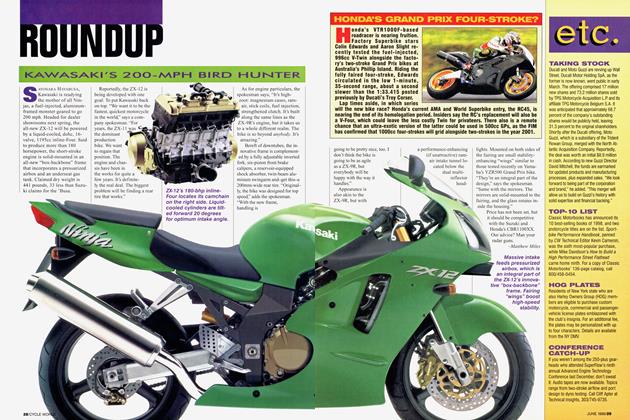

WHAT A DOWNER IT MUST have been for engineer Max Fritz to design a motorcycle, of all things. He'd spent his life as an aircraft designer, and on the eve of World War I joined the prestigious BFW (Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, or Bavarian Aeroplane Works), which metamorphosed into an engine-building offshoot called BMW (Bayerische Motoren Werke) in 1917.

And this factory was no small-potatoes operation. In direct competition with the mighty Mercedes-Benz works, BMW had won the contract to provide its beautiful inline-Six for the new Fokker DVII during the last year of the war.

This fast, deadly and easy-to-fly biplane was so good it made aces out of novice pilots, and is considered by many aviation historians to have been the best fighter of WWI. Baron Van Richthofen, the “Red Knight of Germany,” tested it, but was shot down and killed in his Fokker DR-1 Triplane (luckily for Allied pilots) before the fast DVII reached the front.

How good was this airplane? The Versailles Treaty demanded that all of them be confiscated from Germany, and the blueprints delivered to the Allies.

In other words, Max Fritz had been a player, right in the thick of the Big Time, doing his job all too well to suit the victors.

How humbling, then, to be forbidden by the peace treaty after WWI to make airplanes at all. BMW and BFW did anyway, setting a new altitude record of 32,000 feet. Now the Allies were really ticked off, and confiscated those blueprints and documents.

Finally subdued, the company with the blueand-white propeller emblem grudgingly turned to supplying manufactured parts for air brakes for trains and castings for agricultural machines.

Thrilling stuff.

Eventually, BMW was also contracted to make a small, light engine for the Otto company (of Ottocycle fame). It built an industrial 494cc flat-Twin that fit very nicely in a bike frame, mounted fore and aft. It was sold as a proprietary unit to a number of different motorcycle manufacturers, just as the J.A.P. engine was in England.

Then, in 1922, BMW took over the Helios motorcycle factory and decided to build a bike of its own, and Fritz was turned loose on the drawing board. He paid a licensing fee to Douglas of England, so he could turn the Boxer-Twin sideways, as Douglas had, and then designed an entirely new bike around it.

And the 1923 model R32 was bom. The R stood for Rad, or bike, and the 32...well, maybe it was the company’s 32nd design. Or Max’s sleeve length. Good ring to it, anyway, jal

Suffice it to say, there aren’t many R32s left in the world. Nineteen and twenty-three was a long time ago, and only 3090 were made before its successor, the overheadvalve R42, came along in 1926. Of those, only 10 examples survive, and the bike we have here, folks, is the only complete, original first-year model known to exist.

The oldest BMW in the world.

And it’s sitting in the showroom of Irv Seaver BMW in Orange, California, just a few miles from the Cycle World offices. Which is where I first saw it.

Walked in off the street while visiting California last fall, to say hello to the Bell family (Evan, wife Lois and son Brian) who now own Irv Seaver BMW, old friends and purveyors of somewhat newer BMWs to yours tmly over the years. No sooner had I stepped inside the door than I was knocked out by this absolutely gorgeous old Beemer holding a place of honor in the center of the showroom.

I’m no BMW historian, but I knew it was something special. “That’s the oldest BMW known to exist in the world,” Evan explained quietly, “and I just finished restoring it. I’ve been working on it, off and on, since 1977.”

In the world of motorcycle archaeology, this is kind of like announcing you’ve just finished restoring the True Cross, or maybe King Arthur’s sword. (“Oh, that thing. I found it in the bottom of a lake...”) It gets your attention. So I returned a month later, notebook in hand, promised the opportunity for a short ride.

So. How does one come by a bike of this age and historical importance?

“It was advertised in the BMW Vintage Club of America Bulletin,” Bell says, “and the ad said it was in Berlin. By coincidence, I was going to Germany on a BMW factory tour, so I made arrangements to see it.”

The owner was a man named Hans Kaiser, who owned a motorcycle repair shop in an old Berlin car-

riage house. "I never could get him to fess up to where he got the bike," Bell says. "Hans had a brother in East Berlin, so he may have smuggled it out of East

Germany. The bike was adver tised as `fully restored,' but it was really just an engine sitting in a frame, with no carb or electrics. He was asking $10,000, and I paid him $6500 forit.He wanted

the money so he and his mother

America, and they came to visit us later. I shipped the bike back here in a wooden crate.”

Bell warmed up for the

project by restoring a 1924 R32 he found in Philadelphia, also using that bike for parts patterns. The 1923 restoration still was not easy.

“The rear fender was a mess-rusted, cracked and welded many times by ‘experts.’ I got a modem replacement that was incorrect, so we had

Richard Straman’s car-restoration shop repair this one with lead—18 hours labor. Ron Saul, a machinist friend, made the rear brake ever and footrests, remachined the kickstart lever and worn-out knurls. He also made the saddle pan and rear footrests. Mike Maestas did the leather saddle. The bike was painted by Dan Norton, a perfectionist woodworker friend.”

I remarked on the authentic-looking Continental tires, and Bell said, “I couldn’t find a German tire this size, but these are still being made for rickshaws

in Japan and China, so I took the modern lettering off with a Dremel tool, then took plaster molds off the old, original-style Continentals that came with the bike and filled them with black air-dry rubber. I cut them out with an Exacto knife and glued the letters on with wetsuit cement.”

Just what I’d do.

The mind-boggling details go on and on: Bell made the tooling for a shop to machine the stainlesssteel muffler cones, but he couldn’t find the correct corkscrew baffles and had to make them from welded washers. He also had to make most of the bolts because the 8 x 1mm thread is not available in stainless, and so on. Hundreds and hundreds of hours...

“Old bikes were made by man,” Bell says philosophically, “so everything on them can still be made.” After hearing all these restoration details, I was hesitant to ride the R32-and I’m sure Evan was not altogether anxious to have it flogged through traffic-but we decided a short ride down the side street near his shop and back through the parking lot would be in order.

To start the thing, you:

(1 ) Turn fuel petcock lever, (2) set choke lever at carburetor, (3) retard mag with left handlebar lever, (4) set separate air and throttle levers on right bar open about V4 distance, (5) kick (we push by hand) the kickstart lever through once to prime and once to start (bike starts immediately).

Riding time: (1) Pull in clutch lever, rock backwards and ease tankmounted gearshift lever of the non-constant-mesh (inconstantmesh?) three-speed gearbox back toward you into first, (2) release clutch lever (feels normal and modem), motivate forward, (3) adjust throttle and air levers for desired speed and best running, (4) put feet up on neat cast floorboards, (5) go places.

It would be inaccurate to say this very advanced (for its time) bike feels modem, but it is comfortable. The seat is nice, the big, wide bars easy to steer and the riding position very civilized. The engine sounds rather primitive, chuffy and blatty, like an early farm implement motor off, maybe, a hay bailer or an irrigation pump. The exhaust system blows smoke from both “pepperbox” holes in the sides of the mufflers and puffs out diffuse little clouds from the rear, like miniature smoke signals.

Without the twistgrip that came along on 1926 BMWs and the front brake (1924), it’s still very much of the Antique Contraption school of non-intuitive operation. You operate the bike the way you might run an old shop lathe or printing press, with forthright,

deliberate motions of levers and rods, rather than just riding it.

The brakes, especially, are footed in the past-almost the 19th century. The brake pedal and handlebar lever both push separate, curved pieces of wood (white ash) into a Vshaped groove in a faux drive-pulley hoop on the rear wheel. The foot pedal does most of the stopping. The bike does stop eventually, but I’d rather go up the Alps than down.

Ride is pretty good with the sprung saddle and twin leaf-spring front suspension, but there’s no rear suspension. The perfectly square (68 x 68mm) sidevalve engine moves the bike with moderate briskness down the pavement, and is rated at 8.5 bhp at 3300 rpm, with a supposed top speed of 60 mph. I did not attempt such feats on my short ride. Steering is a little tippy at low speeds, but stabilizes when you get rolling, sort of like a long, low bicycle.

I come back and park, killing the engine with the carburetor levers. And the ride is done. No oil leaks. Fun, but I don’t think I’d want to ride it in modern traffic. This is a bike for a much less crowded world. With a twistgrip and real brakes-and maybe a footshift-however, it would be almost modern.

And it certainly was in 1923, right on the cutting edge.

Strangely, this 76-yearold bike has virtually every piece of the signature BMW layout in place, as we see it right up to the present: shaft drive; BoxerTwin engine set crosswise in the frame; automotivestyle single-plate clutch; fully enclosed ring and pinion; easily removed rear wheel; Bosch electrics; smooth, rounded crankcases with no external oil lines or clutter; elegantly finished parts and a high state of frame finish and welding. It even has Bosch sparkplugs.

What other company has kept such faith with the original rightness of its design over the years? Harley, maybe, but a little less clearly and directly. This was a very refined and classy piece of equipment for the Germans to be manufacturing out of the social and economic ruins of WWI, during a chaotic period of high unemployment and runaway inflation. Remarkably uncompromising in its quality.

And at a time when most motorcycles wore their mechanical hearts on their sleeves and were an amalgam of dripping oil lines, greasy chains and dirtcatching nooks and fuelstained crannies, the BMW stands out as being positively futuristic, stark, clean and elegant as a Sunbeam toaster, or maybe a Braun coffee grinder.

It’s all so tidy for 1923-everything for which BMW has come to stand was in attendance. As Brian Bell points out, “Even the company’s market position is the same now as it was then-building the practical exotic.”

Max Fritz might have finished his drawings and said, “There. There’s your BMW motorcycle for all time,” set down his pencil and turned out the light.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue