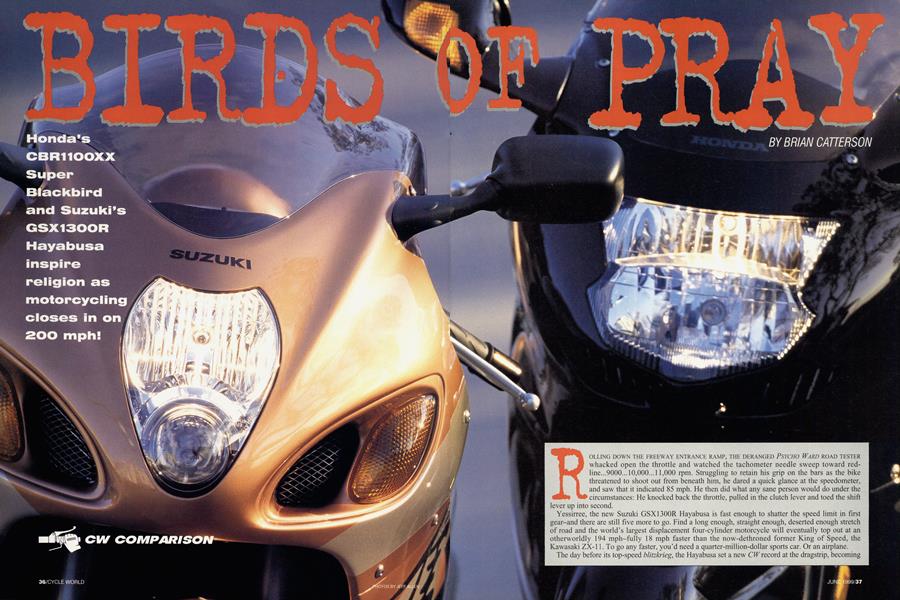

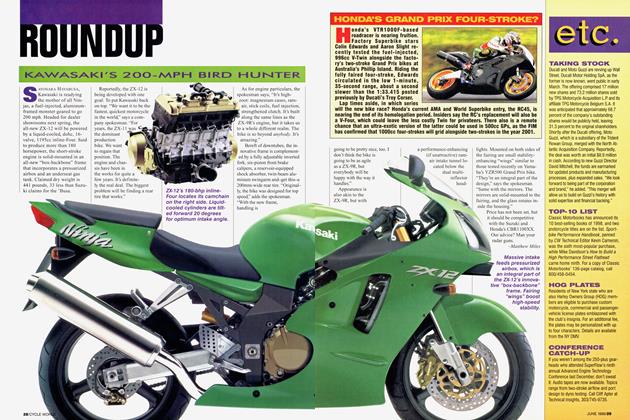

BIRDS OF PRAY

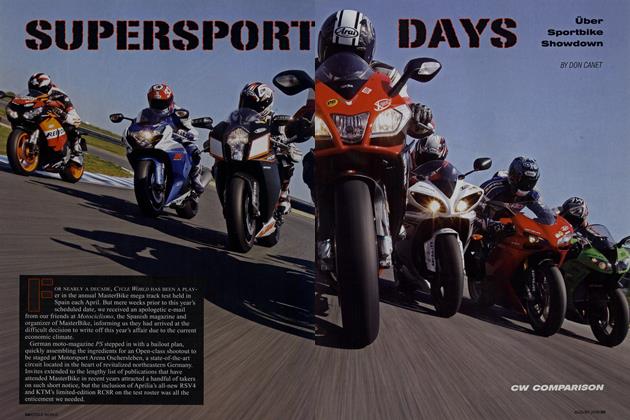

CW COMPARISON

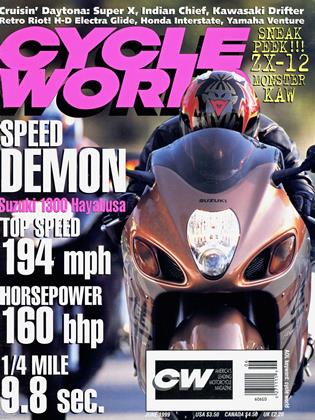

Honda's CBR1100XX Super Blackbird and Suzuki's GSX 1300R Hayabusa inspire religion as motorcycling closes in on 200 mph!

BRIAN CATTERSON

ROLLING DOWN THE FREEWAY ENTRANCE RAMP, THE DERANGED PSYCHO WARD ROAD TESTER whacked open the throttle and watched the tachometer needle sweep toward red-line...9000... 10,000... 11,000 rpm. Struggling to retain his grip on the bars as the bike threatened to shoot out from beneath him, he dared a quick glance at the speedometer, and saw that it indicated 85 mph. He then did what any sane person would do under the circumstances: He knocked back the throttle, pulled in the clutch lever and toed the shift lever up into second.

Yessirree, the new Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa is fast enough to shatter the speed limit in first gear-and there are still five more to go. Find a long enough, straight enough, deserted enough stretch of road and the world’s largest displacement four-cylinder motorcycle will eventually top out at an otherworldly 194 mph-fully 18 mph faster than the now-dethroned former King of Speed, the Kawasaki ZX-11. To go any faster, you’d need a quarter-million-dollar sports car. Or an airplane.

The day before its top-speed blitzb-ieg, the Hayabusa set a new CW record at the dragstrip, becoming the first production motorcycle to break into the nines with a 9.86-second pass at 146 mph. And the day after, the 1300 set a new high-water mark on CWs in-house dynamometer, pumping out 160.5 horsepower and 99.9 foot-pounds of torque at the rear wheel.

If your mission in life is to own the fastest, quickest and most powerful production motorcycle ever made, then stop reading right now and proceed immediately to your local Suzuki dealer with a check for $10,499 (not including tax, license or dealer set-up). Specify whether you want your 1300 in copper/silver or black/gray, and then sit back and wait for delivery. In the meantime, you’ll want to read such books as 101 Ways to Get Out of a Speeding Ticket and Defending Yourself in Traffic Court. Because brother, you’re going to need all the help you can get to keep your license.

If, however, you don’t mind settling for the second-fastest thing on two wheels, consider the $10,999 Honda CBR1100XX. With new fuel-injection and ram-air systems for 1999, this revitalized roadbumer is capable of 177 mph on top, can sprint through the quarter-mile in 10.20 seconds at 137 mph, and puts 133.2 bhp to the rear wheel. Yes, all these numbers pale in comparison to the Suzuki’s, but they beg the question: How fast do you need to go?

Before we get into that, however, a brief history is in order. Nine years ago, Kawasaki’s ZX-11 set the motorcycle world ablaze, its 176-mph top speed going unchallenged for a number of years.

Seven, to be precise, because two years ago, Honda finally answered Kawasaki’s call with the CBR1100XX, which goes by the name “Super Blackbird” everywhere but here. Unfortunately, the original, carbureted Blackbird failed to improve upon the Ninja’s top speed, due in part to circumstances beyond its control.

Motorcycle magazines do not test in a vacuum, which is just as well, because the bikes wouldn’t run very well. And between the time CW tested the ’90 ZX-11 and the ’97 CBR1100XX, deteriorating road conditions forced us to move our top-speed venue from a prime location at sea level to a less ideal site at 2000 feet. The higher elevation, coupled with persistent winds, resulted in speeds that were slower and less consistent. Thus, even after the ZX-11 received upgrades that theoretically should have resulted in higher speeds, it never matched its original velocity.

Oh well, that was then and this is now, and in same-day, back-to-back performance testing, the Hayabusa blasted the Blackbird to smithereens. But that’s just a small part of the overall picture, because in the real world, the performance of these two rocket sleds is much closer than the numbers suggest. As evidence, consider this tidbit from our testing regimen.

On a sunny spring Saturday, two comparably skilled staffers set out from Newport Beach for the hills of northern San Diego County, trading bikes as they went. The duo encountered all manner of roads, from arrow-straight freeways to tied-in-knots byways, and not once did the Suzuki pilot have to wait for the Honda rider to catch up. Given the Hayabusa’s huge power advantage, you’d think it would leave the Blackbird for roadkill, but in the real world, obstacles like comers and stop signs and the California Highway Patrol set limits on how fast we can go. So most of the time, both bikes are going about the same speed-one rider is just twisting the throttle a little farther, is all. Both bikes bristle with details. The Blackbird has a plainbut-purposeful dash that includes all the usual gauges and warning lights, plus a digital clock and a push-to-reset tripmeter. Its mirrors are two-piece-to adjust the rear view, you move only the glass within-and incorporate the front tumsignals. Both the brake and clutch levers are infinitely adjustable via Honda’s familiar thumbwheels.

Riding the Honda and Suzuki back to back, it’s remarkable how similar they are-or maybe it’s not, because they were obviously created with the same mission in mind. Both are powered by fuel-injected, liquid-cooled, 16-valve, dohc inline-Fours with hydraulic clutches, six-speed transmissions and chain final drive. Both have twin-spar aluminum chassis with adjustable suspension, radial-shod 17-inch wheels and triple disc brakes. Both measure about the same distance between axles and weigh close to the same, the Suzuki being slightly shorter and lighter. Both have stacked headlights that slim their frontal areas, plus fully encompassing fairings that expedite their passage through the wind. The Hayabusa just looks...well, either futuristic or butt-ugly, depending on who you ask. If nothing else, it’s distinctive, especially when parked next to the stealth-black ’Bird.

The Hayabusa sets new standards for fit and finish on a Suzuki, with a gorgeous machined top triple-clamp and a faux carbon-fiber dash that somehow manages to not look cheesy. Turn on the ignition key and the instrument panel comes to life, the speedo and tach needles sweeping across their dials and the idiot lights flashing all at once. The ’Busa also has a digital clock, but it goes the ’Bird one better with a digital odometer that toggles between dual tripmeters, each with corresponding fuel-mileage figures. Its adjustablespan front brake lever has not four, but six positions.

Sit on either bike and its singular purpose is apparent. Both are long (for stability) and low (for penetration), with near-horizontal windscreens that only work when the rider is in a racing tuck; sit up at triple-digit speeds and you’ll be blown off the back. The clip-on handlebars angle downward, encouraging an elbows-in posture, while the footpegs are high and rearset, as much to keep the rider’s feet out of the windstream as to maximize cornering clearance. The Honda has a nice bar-to-seat relationship, but its seat-to-peg distance is tight. Conversely, the Suzuki has lower bars that force the rider to lean farther forward, but it offers marginally greater legroom. We’d score comfort as a tie, with the win going to the aftermarket, which will have a field day selling bars and bubbles for both these machines.

Suspension-wise, both bikes work very well. The Suzuki delivers a rough ride in as-delivered trim, the excessive compression damping required to soak up square-edged bumps at supra-legal speeds rendering it uncomfortable at more pedestrian velocities. Should you desire more compliance, you’ll need to back off compression damping considerably. The Blackbird used to come set-up like this, but Honda fine-tuned the low-speed compression damping so that the bike now delivers a relatively plush ride at all times.

Both bikes also score high marks in handling, with precise front-end feedback and superb stability. The Honda’s steering is a cut above the Suzuki’s, however, so neutral and light that you’d swear the Blackbird was the smaller of the two machines. It’s not.

Which one has better brakes is a matter of personal preference. The Blackbird is equipped with the latest development of Honda’s Linked Braking System, which sees both the lever and the pedal actuate both the front and rear brakes, in inverse proportions. The Suzuki is equipped with a traditional separated system, its front brake lever actuating a pair of Tokico six-piston calipers that offer superb stopping power at the expense of a slightly “dead” feeling. Which setup works better? Depends on prevailing conditions and your skill level. Suffice to say that in a panic situation, LBS would give anyone a discernible safety advantage, as it applies maximum stopping power to both wheels in the correct ratio. Think of it as poor man’s ABS.

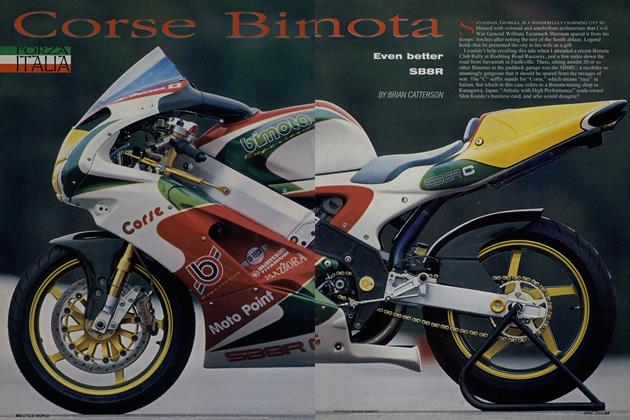

Honda CBR1100XX A Faster than every produc tion motorcycle except one A Typically refined package further improved with fuel injection A Much easier to say "Double-X" than "Haya. .whatever" owns V Slower than the Hayabusa, yet more expensive v Any color you want as long as it's black V Could we please get a "delete" option on the Linked Brakes? Price $10,999 Dryweight 534 lb. Wheelbase 58.7 in. Seat height 31.9 in. Fuel mileage 32 mpg 0-60 mph 2.6 sec. 1/4-mile 10.20 sec. @ 136.95 mph Horsepower . . . 133.2 bhp @ 9400 rpm Torque 81.8 ft.-Ibs. @7150 rpm Top speed 177 mph

In ordinary riding, the Honda’s linked brakes are transparent, but there are some situations in which you can detect it. For example, if you apply the brakes the moment your front wheel reaches the bottom of a hill, while the rear wheel is still slightly unweighted, you can invoke an unwanted skid. The system also makes it difficult to perform stupid journalist tricks such as burnouts (you can’t lock the front brake without also locking the rear), wheelies (stabbing the rear brake pedal to bring the front wheel back down causes the front wheel to stop spinning, killing its gyro effect) and hacked-out comer entries, though the latter are possible provided you transfer enough weight onto the front wheel (see scenario #1). But really, unless you’re a professional photo model or an unabashed showoff, you probably won’t ever realize these limitations.

Not surprisingly, the most significant difference between these two bikes concerns their engines. With 161cc additional displacement (1298cc versus 1 1 37cc), 27 lore horsepower and 18 more foot-pounds of torque, the Hayabusa simply feels more powerful than the Blackbird everywhere. Roll on the throttle in any gear, at any rpm,

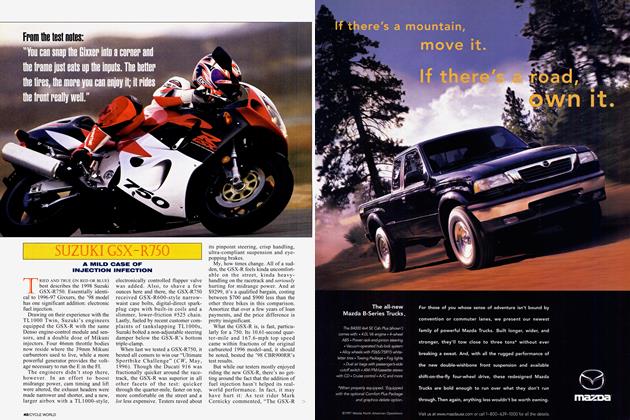

Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa Price..........$10,499 Ups Dry weight.......521 lb. A Distinctive, wind tunnelWheelbase......58.5 in. derived styling Seat height......31.7 in. A Not as big as it looks Fuel mileage.....32 mpg A The new King of Speed! 0-60 mph.......2.6 sec. 1/4-mile.......9.86 sec. Ilowns @ 145.80 mph ▼ Distinctive, wind tunnelHorsepower ... 160.5 bhp derived styling @ 9250 rpm ▼ Should come with an “R” Torque.......99.9 ft.-lb. rating: suitable for mature @ 7550 rpm audiences only Top speed......194 mph ▼ Couldn’t they just have called it the “Falcon?”

and the 1300 responds with arm-stretching urgency, albeit with a little stumble off the bottom from the fuel injection and a slight buzz in the bars. Car guys brag about 0-60-mph times under 6 seconds, but this bike takes just 2.6 seconds, and reaches 100 mph in just 4.9 ticks.

The Honda launches just as hard, taking the same amount of time to reach 60 mph, but it needs a half-second more to hit 100. The new fuel-injection system is flawless, with no abruptness, stumbling or surging at any rpm. A redesigned clutch and harder cush-drive damper work together to reduce driveline lash, eliminating the one nagging complaint we had about past Blackbirds. Though the Honda’s engine is eerily smooth, a bit of gear whine from within makes it sound strained next to the Suzuki’s. But that’s just a figment of our imagination, because in truth, it’s never working that hard.

And that’s the real appeal of these

machines: It’s not so much their outright performance as their potential performance that counts. There’s something about cruising at 75 mph in fourth gear with the throttle barely cracked, the tachometer needle hovering down around 4000 rpm, the engine barely breathing, let alone breaking a sweat, still with half its power reserve untapped. There’s no doubting who owns the road...

So there you have it: two motorcycles, each with stupifying performance, but which ridden conservatively function splendidly in the real world. In many ways, the Honda is the superior motorcycle, its seamless performance polished to a glistening sheen. But considering these bikes’ primary objective-going as fast as possible-the win has to go to the faster of the two. And for the moment, the Suzuki GSX1300R Hayabusa is the fastest production motorcycle on the planet. Everything else is, well, slow.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue