THE GRADUATE

or...How I Survived the Supercamp Shuffle

WIDOW I KNOW GOT married again, to a much younger man, and embarked on the good life, as in her own Corvette. One day she drove into the gas station. "Oh, yeah," the attendant said, "I know this car. Your son was in here yesterday."

Ouch.

She zoomed home at Vette speed and telephoned a pal, a plastic surgeon. "I want everything you've got," she said, "and I want it this very afternoon."

I've been there, in a painful manner of speaking, and done that.

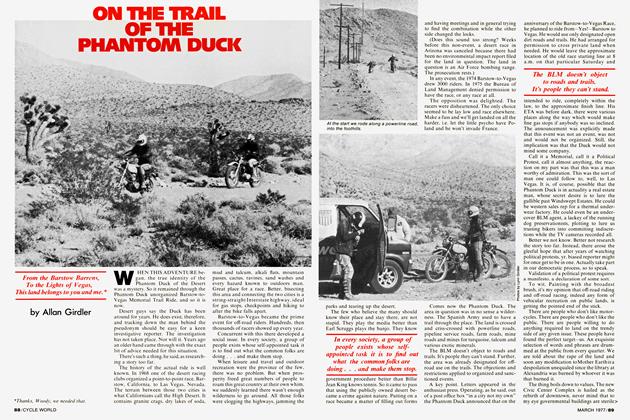

On the occasion of the Vintage Dirt Track Racing Association's Las Vegas Half-Mile, there I was, pitching the bike into Turn 3 at my maximum angle when there was a blast in my ear and the fast guys roosted past me on the outside, blistering me with rocks and teaching me, not for the first time, that I didn't know what I was doing in dirt-track.

Strike me while the shoe is cold, I muttered to myself, 'cause tomorrow Chris Carr and Will Davis will be on my team. Tomorrow I'll be attending the American Supercamp, source of remedial

help for those whose enthusiasm for flat-track outruns their talent.

Such help has been a surprisingly long time coming.

It is a generally acknowledged truth that dirt-track, as devised by American motorcyclists generations ago and refined and improved ever since, is the most skillful and demanding speciality in our sport. Not the fastest, and certainly not the best way to get rich and famous, but dirt-track is the toughest and surest test of talent and skill. As Kenny Roberts proved to the world 20 years ago, if you can throw a motorcycle out of control and make it go and do exactly what you want while it's out of control, every other venue comes easy.

Several years back, responding to numerous requests, Roberts set up a school where aspiring roadracers could train and practice on dirt, honing their skills and reflexes. The school was, and is, for professionals. Meanwhile, the schools for motocross and club-level roadracing are so numerous (see sidebars) that there are directories for them.

Dirt-track, the oldest and the toughest, has remained a discipline for sorcerers and their apprentices.

Comes now Danny Walker, a Colorado-based dirt-tracker who went roadracing to get his full AMA license and discovered he'd made a good career move. Walker retained his enthusiasm for flat-track, though, and noticed that his pavement peers, especially from other countries, knew their racing history. They knew about the

Roberts Revolution and they wanted to follow the example.

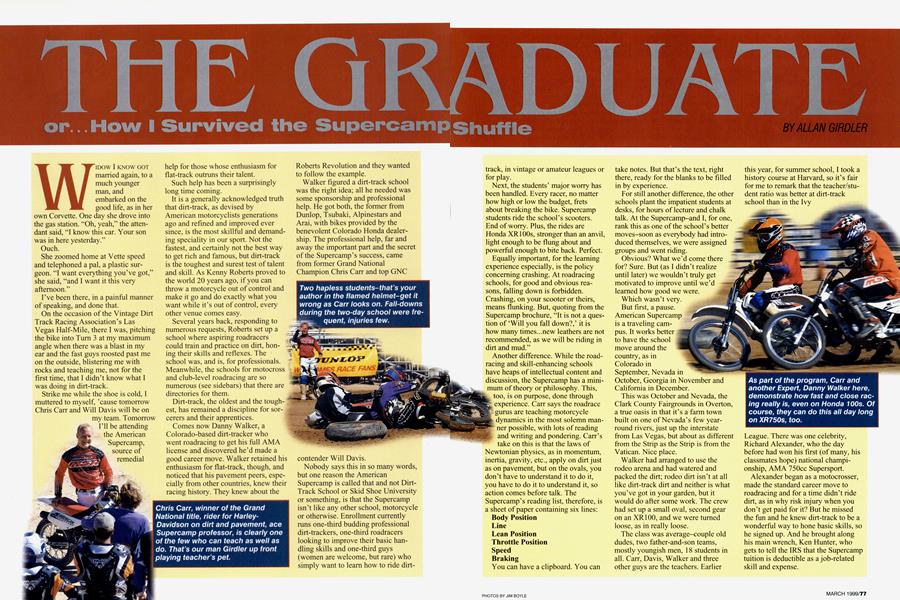

Walker figured a dirt-track school was the right idea; all he needed was some sponsorship and professional help. He got both, the former from Dunlop, Tsubaki, Alpinestars and Arai, with bikes provided by the benevolent Colorado Honda dealership. The professional help, far and away the important part and the secret of the Supercamp's success, came from former Grand National Champion Chris Carr and top GNC

contender Will Davis.

Nobody says this in so many words, but one reason the American Supercamp is called that and not DirtTrack School or Skid Shoe University or something, is that the Supercamp isn't like any other school, motorcycle or otherwise. Enrollment currently runs one-third budding professional dirt-trackers, one-third roadracers looking to improve their basic handling skills and one-third guys (women are welcome, but rare) who simply want to learn how to ride dirttrack, in vintage or amateur leagues or for play.

ALLAN GIRDLER

Next, the students' major worry has been handled. Every racer, no matter how high or low the budget, frets about breaking the bike. Supercamp students ride the school's scooters.

End of worry. Plus, the rides are Honda XRlOOs, stronger than an anvil, light enough to be flung about and powerful enough to bite back. Perfect.

Equally important, for the learning experience especially, is the policy concerning crashing. At roadracing schools, for good and obvious reasons, falling down is forbidden. Crashing, on your scooter or theirs, means flunking. But, quoting from the Supercamp brochure, "It is not a question of ‘Will you fall down?,' it is how many times...new leathers are not recommended, as we will be riding in dirt and mud."

Another difference. While the roadracing and skill-enhancing schools have heaps of intellectual content and discussion, the Supercamp has a minimum of theory or philosophy. This, too, is on purpose, done through experience. Carr says the roadrace gurus are teaching motorcycle dynamics in the most solemn manner possible, with lots of reading and writing and pondering. Carr's take on this is that the laws of Newtonian physics, as in momentum, inertia, gravity, etc., apply on dirt just as on pavement, but on the ovals, you don't have to understand it to do it, you have to do it to understand it, so action comes before talk. The Supercamp's reading list, therefore, is a sheet of paper containing six lines: Body Position Line

Lean Position Throttle Position Speed Braking

You can have a clipboard. You can

take notes. But that's the text, right there, ready for the blanks to be filled in by experience.

For still another difference, the other schools plant the impatient students at desks, for hours of lecture and chalk talk. At the Supercamp-and I, for one, rank this as one of the school's better moves-soon as everybody had introduced themselves, we were assigned groups and went riding.

Obvious? What we'd come there for? Sure. But (as I didn't realize until later) we wouldn't truly get motivated to improve until we'd learned how good we were.

Which wasn't very.

But first, a pause.

American Supercamp is a traveling campus. It works better to have the school move around the country, as in Colorado in September, Nevada in October, Georgia in November and California in December.

This was October and Nevada, the Clark County Fairgrounds in Overton, a true oasis in that it's a farm town built on one of Nevada's few yearround rivers, just up the interstate from Las Vegas, but about as different from the Strip as the Strip is from the Vatican. Nice place.

Walker had arranged to use the rodeo arena and had watered and packed the dirt; rodeo dirt isn't at all like dirt-track dirt and neither is what you've got in your garden, but it would do after some work. The crew had set up a small oval, second gear on an XRIOO, and we were turned loose, as in really loose.

The class was average-couple old dudes, two father-and-son teams, mostly youngish men, 18 students in all. Carr, Davis, Walker and three other guys are the teachers. Earlier

this year, for summer school, I took a history course at Harvard, so it's fair for me to remark that the teacher/stu dent ratio was better at dirt-track school than in the Ivy

League. There was one celebrity, Richard Alexander, who the day before had won his first (of many, his classmates hope) national championship, AMA 750cc Supersport.

Alexander began as a motocrosser, made the standard career move to roadracing and for a time didn't ride dirt, as in why risk injury when you don't get paid for it? But he missed the fun and he knew dirt-track to be a wonderful way to hone basic skills, so he signed up. And he brought along his main wrench, Ken Hunter, who gets to tell the 1RS that the Supercamp tuition is deductible as a job-related skill and expense.

Speaking of that, this article isn't one of those deals where the writer is a guest of the subject and the writer says how wonderful the subject is.

The tuition here ($500) was paid in full, out of the writer's own pocket and yes, I plan to deduct it. What else are accountants for?

Anyway, "Laugh-In" or the homevideo people would have paid big bucks for a tape of that first session. We were all clumsy, rude and aggressive. We spun out, tipped over, braked too soon and/or too late. We sideswiped each other, fell on each other, T-boned each other.

But we were there to learn. After the first sessions, we got some instruction and some reports on our styles. Armed with the basics and some humility, we tried again-power off, pitch it, power on, bank it, get straight, power off, over and over, first to the left and then to the right. This went on for a couple of hours, making it clear, first, that having one session on the track and two to recover and observe was a good idea and, second, we would have a lot of track time.

Carr and Davis are active partners in this enterprise; that is, it's not like where baseball stars put their names on the front of the saloon but don't go there. Note here that on this occasion Carr was leading the Grand National series, with one race to go, and Davis was fourth in the standings, with a mathematical chance to win the title for the first time. But here they were, banging bars, slamming the door on each other, having a whale of a good time...and risking limb if not life. For untalented us, which is to say, for sport.

We began to catch on, with each learning according to his abilities, and we developed a form of on-track etiquette.

Abraham Lincoln would have been right at home. He came from a town where, he used to say, every man knew who he could ship and who could ship him.

So it was in our groups, that is, there were two guys faster than me, one about my speed and two slower, so as we lapped we got used to the closeness and the contact.

When the faster man shows you a wheel, you get wider and hold on; when you show the slower man a wheel, expect him to keep his line, and if he's really slow, don't pass where he might lose it.

Because we'd lost daylight to trackprep time, the school guys rigged lights and we rode deep into the evening. The learning curve was still going up, and by the end of the evening session I was doing feet-up slides left and right and having as much fun as you can have with your goggles steamed up.

Next moming-did I mention that each Supercamp runs for two days?-Carr was the instructor-in-chief, and most of what he told us, and showed us, is that dirt-track is fun. That's what it's supposed to be, Carr said, and we mustn't lose sight of that fact.

Happens we needed to keep that in mind. During one of the early sessions, one of the kids collided with another guy in his group and the other rider, kind of a prankster on first impression, leaped to his feet and did a mock victory dance.

In fun. He hadn't noticed that the kid's boot was jammed between chain and sprocket. The dad did notice and he charged the other man. For a moment it looked as if a hockey game was going to break out. But there was just the one sorehead and 20 or so cooler heads, so peace was restored. The kid wasn't hurt-in fact, a swollen knee was the total injury for two days of thrills and spills-but we were reminded that manners make life smoother. And then we all went back to banging bars, no harm done.

Carr, especially, is articulate and aware. He told us about one Supercamp where he had to deal with one student's "shyness."

"I'd show him a wheel and he'd get uptight, slow down and move away," Carr said. "I'd tell him not to do that. Finally, he held on...and highsided me! I said, ‘That's what I've been trying to teach you. You've got to get used to being inches apart.' "

Then we moved to Donut Drill, with Carr standing astride a banked bike, revving the engine, dropping the clutch and pivoting the bike around his planted foot, first to the left and then to the right. Practice this until it's a habit, Carr said, because turning the bike is the essence of dirt-track and once you've got the technique, the speed and size of the bike are only details.

"I want you to turn on a dime," he preached, "and not on a silver dollar." And then this, unexpected: "Turning a motorcycle is really a mental exercise," Carr said. "It's as much psychology as anything." Hmmm...

Supercamp school is race-based, but it's not supposed to send us all to the Pro ranks. Rather, it's about potential, and how to reach it. The instructors rode with us on the short-track. Sometimes they'd follow, to see where we were going wrong, and sometimes they'd lead, to show us how and where we were supposed to go. Next, the track was converted to a kidney shape, a TT track minus jump. And it was heavily watered-turned to mud, in fact. Mud Drill, they called it,

and the idea was that the more slippery the surface, the more we'd develop throttle control.

That was the theory. In practice, what we mostly did was fall down. After a couple of sessions the track was allowed to dry out, and we got back up to speed.

Here, the instruction really was individual. In my own case, the instructors mostly told me to roll the throttle on, sit higher in the turns and get that inside elbow straight! All of which I did my best to do.

At the close of school, after two full days of riding as hard and fast as we could, meaning also we were harder and faster than we'd been, each of us got an in-depth critique.

Done right. Carr used the most diplomatic manner I could imagine. For the speed I was riding, he said, I was riding perfectly.

!~~se while I looked modest.

Thing was, Carr went on, the way I was riding meant I could never go any faster than I was going. Carr explained: What I lacked was entry speed. I was running it in too slowly and then using the throttle to make the bike turn, while what I needed to do was come in fast and pitch the bike, turning with momentum and using the power to, well, power out,

" and regain the traction

I'd just thrown away.

"You'll have to make that commitment," Carr said, "so we can take you to the next level."

Fair enough. And honest, and proof they really do care, and aren't just in it to shine us on and collect our money.

Then we had the official good-bye ceremony, in which we were told we'd done better than predicted, and

asked if we'd had fun, to which we chorused Sure Did.

During this, I remembered years and years ago when I bought my first dual-purpose bike, a Honda XL250. Never mind that it was heavy and slow, I loved it and got every extra on the market: exhaust pipe, fork kit, shocks, skid pad, knobby tires, etc.

One day I told a friend, a low-number desert Expert, that my XL was "really handling good."

He gave me a patient look.

"It may be handling better," he said slowly, "but it's never going to handle good."

So, okay, I probably won't ever be good at dirt-track. But thanks to American Supercamp, I'm getting better. □

For more information, contact American Supercamp at 217 Blossom Dr., Loveland, CO 80537; 970/669-4322.