TDC

Something new

Kevin Cameron

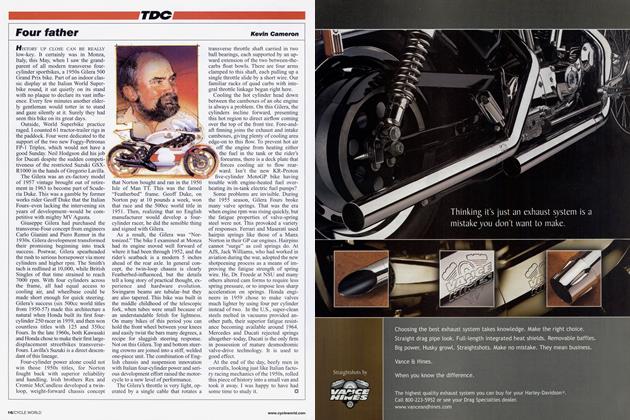

I WALKED AROUND THE FALLEN MONSTER and tried to come to grips with what I saw. A bent and twisted four-bladed steel propeller defined one end, and a mass of twisted sheet and tubing constituted the other. In between, under smooth nacelle aluminum and black cooling shrouds was a 28-cylinder, 4360-cubic-inch radial aircraft engine.

As a boy in a science museum, I had watched a cutaway display version of this thing turn majestically at the push of a button. As a much smaller boy, I had stared at photos of such complexity in an encyclopedia. Some early impressions don’t leave us. Engines have never deserted me as a source of fascination.

Although I was also drawn to cars, they were big and expensive, out of my scale. They needed garages and lifts and hoists that I didn’t have. And they weren’t really machines as much as they were living rooms. I could use them, but I didn’t love them. That put motorcycles at the top of my list.

Aircraft engines came into being, not as part of the give-and-take of the free market, but as emergency productions funded by governments in the shadow of war. Once the basic R&D was done, the constructional principles were then applied to commercial engines. Aircraft engines, like the transistor, radar and atomic power, are the pyramids of our age, undertakings too large for individuals or even for large corporations. The products contain the very best technology and materials available in their time. In a way, aircraft engines are the powerplants of the ultimate factory teams-the air forces of nations.

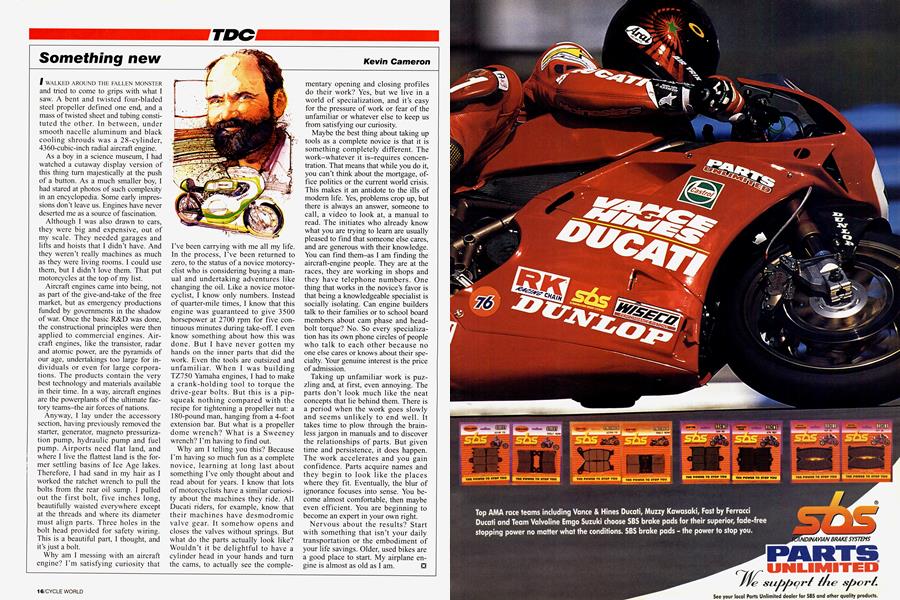

Anyway, I lay under the accessory section, having previously removed the starter, generator, magneto pressurization pump, hydraulic pump and fuel pump. Airports need flat land, and where I live the flattest land is the former settling basins of Ice Age lakes. Therefore, I had sand in my hair as I worked the ratchet wrench to pull the bolts from the rear oil sump. I pulled out the first bolt, five inches long, beautifully waisted everywhere except at the threads and where its diameter must align parts. Three holes in the bolt head provided for safety wiring. This is a beautiful part, I thought, and it’s just a bolt.

Why am I messing with an aircraft engine? I’m satisfying curiosity that

I’ve been carrying with me all my life. In the process, I’ve been returned to zero, to the status of a novice motorcyclist who is considering buying a manual and undertaking adventures like changing the oil. Like a novice motorcyclist, I know only numbers. Instead of quarter-mile times, I know that this engine was guaranteed to give 3500 horsepower at 2700 rpm for five continuous minutes during take-off. I even know something about how this was done. But I have never gotten my hands on the inner parts that did the work. Even the tools are outsized and unfamiliar. When I was building TZ750 Yamaha engines, I had to make a crank-holding tool to torque the drive-gear bolts. But this is a pipsqueak nothing compared with the recipe for tightening a propeller nut: a 180-pound man, hanging from a 4-foot extension bar. But what is a propeller dome wrench? What is a Sweeney wrench? I’m having to find out.

Why am I telling you this? Because I’m having so much fun as a complete novice, learning at long last about something I’ve only thought about and read about for years. I know that lots of motorcyclists have a similar curiosity about the machines they ride. All Ducati riders, for example, know that their machines have desmodromic valve gear. It somehow opens and closes the valves without springs. But what do the parts actually look like? Wouldn’t it be delightful to have a cylinder head in your hands and turn the cams, to actually see the comple-

mentary opening and closing profiles do their work? Yes, but we live in a world of specialization, and it’s easy for the pressure of work or fear of the unfamiliar or whatever else to keep us from satisfying our curiosity.

Maybe the best thing about taking up tools as a complete novice is that it is something completely different. The work-whatever it is-requires concentration. That means that while you do it, you can’t think about the mortgage, office politics or the current world crisis. This makes it an antidote to the ills of modem life. Yes, problems crop up, but there is always an answer, someone to call, a video to look at, a manual to read. The initiates who already know what you are trying to learn are usually pleased to find that someone else cares, and are generous with their knowledge. You can find them-as I am finding the aircraft-engine people. They are at the races, they are working in shops and they have telephone numbers. One thing that works in the novice’s favor is that being a knowledgeable specialist is socially isolating. Can engine builders talk to their families or to school board members about cam phase and headbolt torque? No. So every specialization has its own phone circles of people who talk to each other because no one else cares or knows about their specialty. Your genuine interest is the price of admission.

Taking up unfamiliar work is puzzling and, at first, even annoying. The parts don’t look much like the neat concepts that lie behind them. There is a period when the work goes slowly and seems unlikely to end well. It takes time to plow through the brainless jargon in manuals and to discover the relationships of parts. But given time and persistence, it does happen. The work accelerates and you gain confidence. Parts acquire names and they begin to look like the places where they fit. Eventually, the blur of ignorance focuses into sense. You become almost comfortable, then maybe even efficient. You are beginning to become an expert in your own right.

Nervous about the results? Start with something that isn’t your daily transportation or the embodiment of your life savings. Older, used bikes are a good place to start. My airplane engine is almost as old as I am. U