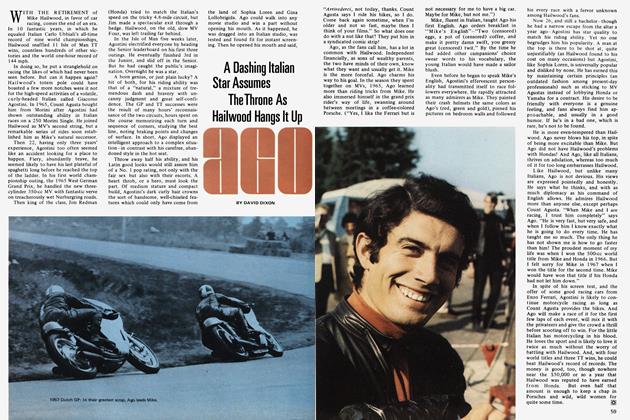

Baja 100

The Harley that time forgot

JIMMY LEWIS

EERIE, THE SILENCE OF A DESERT SO CROWDED WITH people. Waiting. All eyes focused on a banner held high a quarter-mile away, counting down the seconds `til it dropped... BRRRRAAAAPPPP!!!

Like an explosion thundering off the desert floor, hundreds of dirtbikes from the pre-silencer era headed for the smokebomb and the hills beyond, bounding across sand, ditches, rocks and whatever else the desert had up its ancient sleeve.

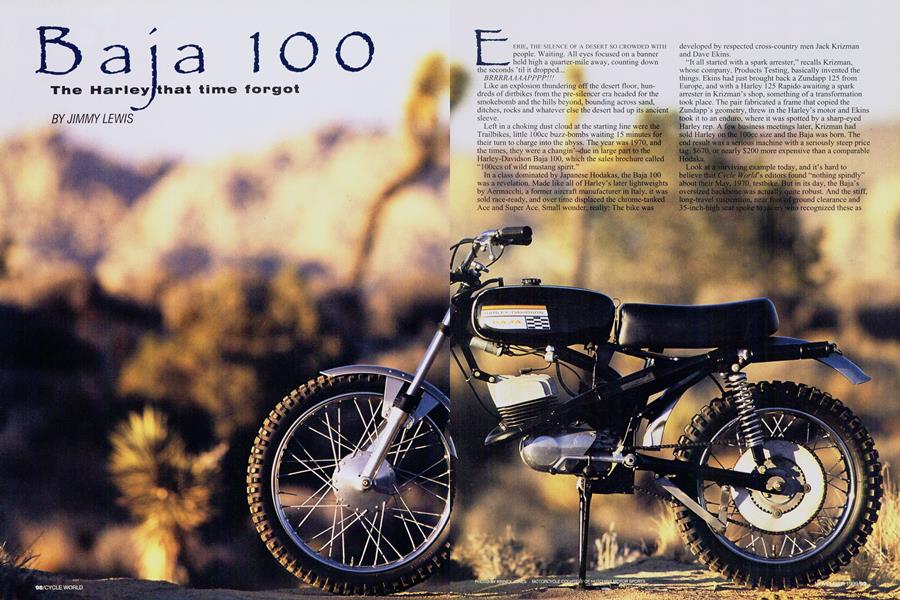

Left in a choking dust cloud at the starting line were the Trailbikes, little lOOcc buzz-bombs waiting 15 minutes for their turn to charge into the abyss. The year was 1970, and the times, they were a changin’-due in large part to the Harley-Davidson Baja 100, which the sales brochure called “l00ccs of wild mustang spirit.”

In a class dominated by Japanese Hodakas, the Baja 100 was a revelation. Made like all of Harley’s later lightweights by Aermacchi, a former aircraft manufacturer in Italy, it was sold race-ready, and over time displaced the chrome-tanked Ace and Super Ace. Small wonder, really: The bike was

developed by respected cross-country men Jack Krizman and Dave Ekins.

“It all started with a spark arrester,” recalls Krizman, whose company, Products Testing, basically invented the things. Ekins had just brought back a Zundapp 125 from Europe, and with a Harley 125 Rapido awaiting a spark arrester in Krizman’s shop, something of a transformation took place. The pair fabricated a frame that copied the Zundapp’s geometry, threw in the Harley’s motor and Ekins Jook it to an enduro, where it was spotted by a sharp-eyed Harley rep. A few business meetings later, Krizman had sold Harley on the lOOcc size and the Baja was bom. The end result was a serious machine with a seriously steep price tag: $670, or nearly $200 more expensive than a comparable Hodaka.

Look at t~rvivin~ example today, and it's hard to believe that cve1c'~~orld's editors found "nothing spindly" about their May. 1970. testhike~ut in its day, the Baja's oversized backbone :w~ actuath~q te robust. And the stiff, long-~a~t~ispcnsio;i, near fo~ö ound clearance and 35-tnch-hk~~~cat woke `0 aCers o rc.ognized these as modifications they wouldn’t have to perform themselves. Even the carb, a 24mm Dell’Orto, was large for a 100, helping the sleeved-down Rapido engine pump out an earth-chucking 10-12 horsepower.

baja 100

So popular were Baja 100s that they played a key role in the development of many of the day’s up-and-coming desert racers. One such youngster was Bruce Ogilvie, now a senior product evaluator at American Honda with a résumé that includes numerous major desert-racing victories over a 20-year span. Armed with his trusty Harley, Bruce O’ advanced from Novice to Amateur in just four months, and to Expert in five more. As an Expert, he clawed his way down to ever-lower digits in the highly competitive Trailbike class of the District 37 desert series. Eyes focused on the elusive number-one plate carried by Jack Morgan (1970, Hodaka), Terry Clark (1971, H-D) and Cordis Brooks (1972, DKW), Ogilvie and his ilk went so fast on their 100s that officials eventually amended the starting procedure to include the Trailbikes in the Expert/Amateur starting wave, rather than delaying them as they had before. Desert racing in the early ’70s was a simpler sport. Note one of Ogilvie’s first modifications: the addition of a genuine knobby rear tire, replacing the standard trials-uni versai. But with the increased traction came transmission troubles. “Once you got it going, you didn’t ever blip the throttle, ’cause you’d lose miles per hour. We’d just slam gears,” recalls Ogilvie. Wide-open downshifts took their toll on fourth gear, or the primary gears. The bike didn’t have the power to break things on its own, but rider abuse certainly could.

“We just bought it and rode it stock,” continues Ogilvie. “Heck, I was just learning to

ride in the desert. And there was really no source of info like you have today with all the magazines.”

About the time that Ogilvie began riding his Baja fast enough to break frames in half, he caught the eye of

Dale Marschke of Dale’s Modern Cycle in San Bernardino, California. Dale’s lent Ogilvie some much needed support, and the Harley factory helped, too, kicking in as much as $50 per week.

About the same time, an even younger rider, Larry Roeseler, was chasing the same goal. Carrying number 29 when he started riding Harleys, L.R. dropped all the way to number four at the end of the 1971 season. And he wasn’t alone: Baja 100 riders won 47 of 51 races in the Trailbike class that season, and grabbed eight of the top 10 positions in year-end district points. Terry Clark won the number-one plate, followed by Mitch Mayes as number two, Jim Sumners as number three, Randy Milligan as number six and Mike Hayes as number nine.

Ogilvie, then 17 years old, grabbed the 10th spot-not too shabby considering his ex-BSA factory-rider father, Don Ogilvie, then a youthful 42, finished seventh. “It took me a

year-and-a-half to beat Pops!” chuckles the younger Ogilvie.

Roeseler continued to win races, marching on to the number-two plate in ’72, and then his first number one as a 16-year-old in ’73. “It was sort of my first factory ride. I’d just show up and race-the bike was already prepped and waiting,” recounts Roeseler. He backed up that performance by again winning the number-one plate in ’74, with Ogilvie number two courtesy of a Barstow-to-Vegas DNF.

Roeseler never got to go for the hattrick, however, as Harley dropped the Baja 100 from its 1975 lineup, replacing it with the dual-purpose SR 100.

The Motor Company’s desert-racing program changed accordingly, switching its focus to the new SX250, which Ogilvie and Roeseler rode to the win in the 1975 Baja 500 (see sidebar).

Three years later, Harley pulled the plug on its lightweight division, sold the Italian factory to Cagiva and never looked back, content to churn out bigbore boulevard bikes for the eager masses. But as you now know, there was a time when Harley built racewinning real dirtbikes. n

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

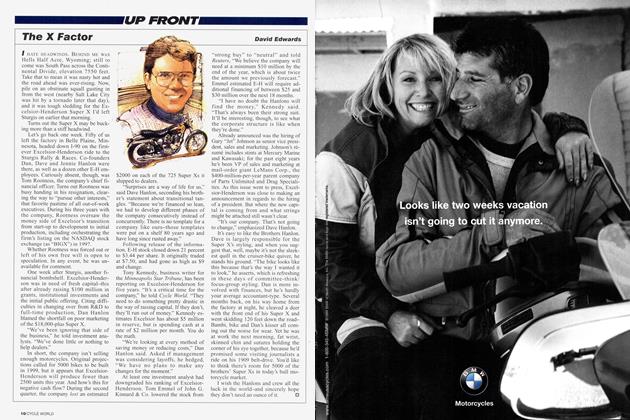

Up Front

Up FrontThe X Factor

November 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWhat Your Bike Says About You

November 1999 By Peter Egan -

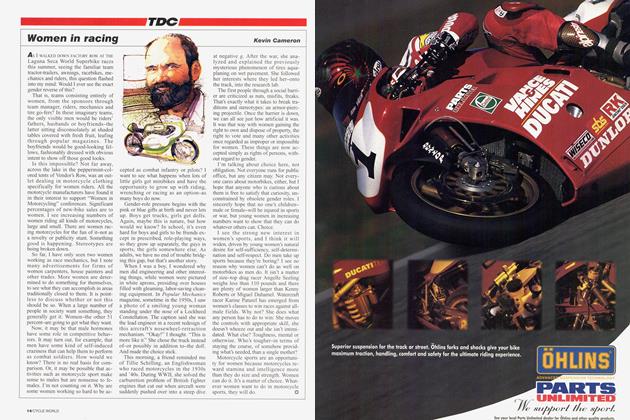

TDC

TDCWomen In Racing

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Hotshots

November 1999 -

Roundup

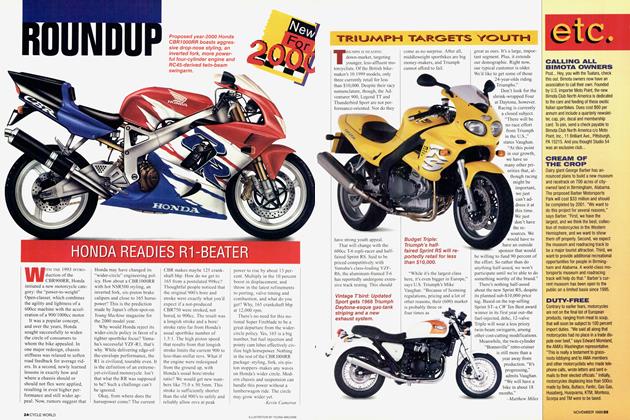

RoundupHonda Readies R1-Beater

November 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupTriumph Targets Youth

November 1999 By Matthew Miles