Red Rocket's Glare

Mike Hailwood Evoluzione : Ducati looks forward while looking back

BRIAN CATTERSON

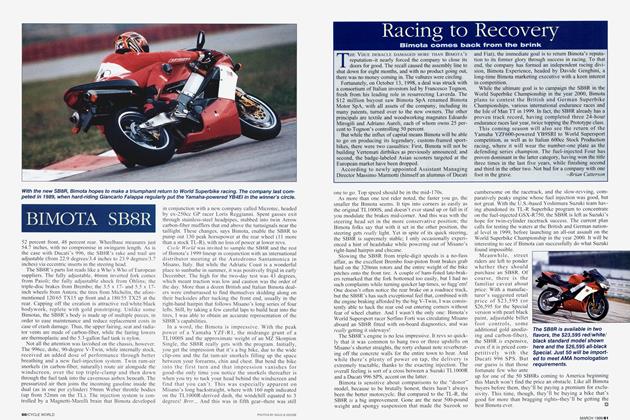

THOSE WHO WORRY THAT BLAND, BLACK AND GRAY sport-tourers are harbingers of the Americanization of Ducati, take heart: Italian design is alive and well and thriving in the MH900e Mike Hailwood Evoluzione that stole the show recently at Intermot in Munich, Germany.

More than a mere concept bike, the Pierre Terblanchedesigned “neo-classic” is intended to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Hailwood’s victory in the Isle of Man TT while simultaneously showing one direction motorcycle design might take in the future. And if the response from the Munich Show has any bearing, this is one prototype that just might make it into production.

So when Ducati invited journalists to the formal introduction of the new ST4 sport-tourer at its Borgo Panigale headquarters, I seized the opportunity to log some face time with Mr. Terblanche. After all, I’d already ridden the ST4, and this Hailwood bike looked intriguing...

One casualty of TPG’s buyout of Ducati was the loss of the Cagiva Research Center, where the majority of recent Ducati models were designed. But the MH900e (along with the newgeneration 900SS) was designed in Birmingham, England, at a company called Futura-with Terblanche overseeing, of course. Thus it is being trumpeted as a test of new technology that will be incorporated in the Ducati Design Center slated to be built within the next two years.

The term “computer-aided design” (CAD) flatters our silicon-based companions, because the computer traditionally has served as a sort of middle step between design and production. After modeling in clay or foam, a designer would take detailed measurements of his hand-made prototype and input these figures into his computer. He then printed out mechanical drawings that he forwarded to the machinists who actually produced the parts.

But now, the advent of more sophisticated CAD programs is allowing the designer to create complex surfaces directly on his computer screen. From there, it’s a small step to a rapid-prototyping machine, which uses a laser to cut out two-dimensional chunks of cardboard that can be glued together to form a threedimensional representation of the finished component. Or, in the most recent twist, he can instruct a CNC machine to mill a three-dimensional prototype out of clay, foam, resin or, if he’s confident, to go straight to metal, with no modeling required. As Terblanche says, “We’re looking for a way to get the same result with less physical effort.”

Working from a digital photograph of a real motorcycle saves time, too, because it gives the designer a set of “hard” points-the location of the engine mounts, steering head, swingarm pivot, axles, etc.-on which to base his work. The original design for the Evoluzione, in fact, was sketched atop a photo of a current 900SS.

Using this new technology enabled Terblanche and his team to create the MH900e in just 11 weeks, a mere five days of which were spent physically modeling. But as the designer is quick to point out, that time frame discounts much of the foresight that went into the project.

“I think it’s wrong to claim we did it in 11 weeks,” admits the expatriate South African. “It was built in 11 weeks, but a lot of the thinking had been done before hand. I’ve been a Ducatista since Cook Neilson blew off the Japanese at Daytona in 1977. I’ve wanted to build this bike for about 12, 13, 14 years. So when they gave me the go-ahead, I didn’t have to do much more than dig into my pile of sketches.”

The obvious question is why go to the bother of designing an all-new motorcycle when you could just throw a tricolore paint scheme on an existing model and christen it the Mike Hailwood Replica, as was pretty much the case with the original 1980 MHR. Well, for one, that lacks passion, the cornerstone of all things Italian. And second, as Terblanche proclaims, “Those are Castrol colors, not Ducati colors. Red and silver are our official race-team colors from the era. Besides, green just looks old.

“I thought maybe the thing would be to not go too retro,” Terblanche continues, “and to use the best of modern technology combined with clues from the past, the way the Volkswagen Beetle has. We wanted to re-create the feel of the old bikes, where the engine was the most important part.”

eart of the project, then, is the 90-degree V-Twin sourced from the current 900SS. Already similar in layout to the legendary, towershaft Twins, this was given an old-fashioned appearance via the addition of a cosmetic cover that resembles the finned deep sumps of the era. And while time did not allow for it prior to the unveiling, the plan calls for machining louvers into the “sump” front and rear, and housing an oil cooler inside. Adding to the old-fashioned look are the unfinished aluminum engine cases, plus the brightly polished cambelt, clutch and ignition covers, the latter sporting a nicely engraved Ducati badge.

But while the clutch cover may recall the old, there’s nothing nostalgic about the dry clutch itself. The high-tech, slipper-type device features just three carbon-carbon friction plates, a diaphragm spring and a titanium basket made by Poggipolini in Italy; total weight is said to be just 800 grams. No less modem are the Gill ignition coils, which bolt directly to the cylinder heads and are joined to the sparkplugs by the caps alone, with no leads required.

Housing the engine is a quintessential, red-painted, steeltrellis frame, the specifications of which closely approximate those of a 916. Terblanche’s stated goal was to make the MH900e handle as well as a 916, or better, because at a claimed 363 pounds, the new bike weighs substantially less.

As on the 900SS, the swingarm pivots directly in the engine cases, with no outside support from the frame. The elegant, single-sided, bridged swingarm represents a departure for Ducati, because like the frame, it is made of redpainted steel rather than aluminum. A Swedish Öhlins shock, stripped of its gold-anodized finish and with its trademark yellow spring painted black, supports the rear end without the aid of a linkage, while a similarly silver-tinted Japanese Showa inverted fork upholds the front. There was talk of using a conventional fork and twin shocks, but these were rejected as too conservative. A Dutch Hyperpro steering damper is positioned crossways behind the steering head, bolted to the brightly polished, curving top triple-clamp.

The dichotomy of old and new continues with the brakes. Manufactured in Slovenia (which used to be part of Yugoslavia), the single front disc is made of a space-age material called Selcom, a combination of silesium and carbon. Said to combine the best features of carbon and castiron, it resembles a pebbly road glistening at sunset and glows red when hot. Terblanche handed me the rear rotor he’d received too late for the unveiling, and it felt about as heavy as a CD. A compact disc-1 chuckled to myself at the doubleentendre. The front disc is grasped by an Italian Brembo fourpiston caliper, painted black to recall the old, while a similarly painted, single-piston Brembo caliper grasps a steel disc at the rear. Interestingly, the old-fashioned, machinedaluminum fluid reservoir on the right clip-on is shared by the front brake and hydraulically actuated clutch.

Continuing our trip down memory lane, the silver-painted, five-spoke wheels are meant to emulate venerable Campagnolo hoops, though they’re much, much wider-the massive 200/50 ZR17 rear Michelin Hi-Sport Radial is about 50 percent wider than its ’70s counterpart.

Crowning glory, though, is the one-piece, rotationally molded nylon fairing/fuel tank. The battery and all other ancillary electrical components attach to the underside of the body, so that lifting it off reveals the bare mechanicals. A silver matte panel on the tank top gives access to the air filter and fuses.

The abbreviated, highly sculpted tailpiece is no less lovely, and houses a luxurious, Connolly leather saddle. As on a 916, twin exhausts protrude from beneath the tail. Black enamel-baked, stainless-steel headers bolt to the exhaust ports with Pantah-style finned collars, and stub into a massive, underseat aluminum muffler box that was pressed in two halves, welded together, then polished. Spent gases exit laterally through SuperTrapp-style diffuser discs, leaving the tips of the twin “megaphones” to house the tumsignals; internal wire sleeves are said to be able to withstand temperatures of up to 500 degrees.

Things only get weirder from there. Protruding downward from the exhaust tips is a die-cast aluminum bracket meant to support the diminutive taillight and license plate. But the most intriguing component is the rearward-aiming video camera, the view from which is displayed on a cockpit video monitor in lieu of unsightly mirrors. This sits to the left of a traditional, white-faced tachometer, while a digital bicycle speedometer completes the spartan dash. A futuristic, French Valeo homofocal headlamp with chrome bezel lights the way.

Whether examined in part or in full, this bike glistens like jewelry, and is gorgeous from any angle.

“It’s got a lot of planned form,” explains Terblanche. “People always photograph bikes in side view, but you don’t see them that way. You actually see the top, like a sports car.

“I think sportbikes are the easiest things to design in a way,” he continues, “because after you’ve finished the bodywork, you can just tack all the stuff wherever you find the space. I’ve begun to follow the custom-bike builders; I’ve become a bit of a Harley fan. As far as design goes, they’re actually very advanced. They’ve managed to make the bikes look undesigned. And that’s the thing-to try to get the balance between looking like some guy made it at home with a lot of passion and being professionally designed.”

Terblanche points to the front fender. Covering only the forward portion of the tire, it is joined to the right-side fork slider by a tubular hanger that recalls a ’70s fork brace.

“Clever,” I remark.

“It’s Custom Chrome!” says Terblanche, in deference to the acclaimed Harley accessory company. “The bits on this bike appeal to people the same way a custom Harley does.”

While I’d love to be able to tell you how the MH900e works, I can’t. Never mind the unscrupulous British magazine whose cover showed it coasting downhill with a rider tucked-in, the prototype sadly isn’t a runner. Twist the throttle and you’ll find there’s no return spring; toe the shifter and it moves freely. There also apparently wasn’t any consideration given to theft prevention-there’s no ignition key or fork lock-but in fact, this was no oversight, as a voicerecognition system is envisioned should the bike reach production.

And when might that be? Good question, though according to Terblanche, the issue is not if the MH900e will reach production, but when.

“The response has been extremely good,” he declares. “The question now is whether we build 200 units at very high cost or 2000 at slightly lower cost. Maybe we’ll do both, and offer a few with exactly the same specification as this one, and the rest with slightly more normal components.” Meanwhile, we can't help wondering what happened to the street version of the Supermono racebike that earned Terblanche his first accolades...

h well, even if the Mike Hailwood Evoluzione never reaches production, it's reassuring just to know that Ducati hasn't lost the plot. And in fact, many of the ideas seen on the MH900e may live on in other models.

"This was meant to be a concept bike," says Terbianche, "and in many ways, it anticipates what we'll be doing on our other products-as far as finishes, the cleanliness, trying to get back to being very essential, cleaning it up a bit. "This is a good indication of what the Monster could look like, for example. We could tidy it up, put the ST2's sus pension on it and that could be the next-generation produc tion hike"

As Terbianche says this, his enthusiasm is palpable, genuine. I spend the better part of the day with him, and I never get the feeling that I am intruding upon his time. To the contrary, there's little doubt he enjoys talking about this stuff immensely.

It's only when a superior instructs him to anange turttier detail photos of the bike for my story that he complains, saying, "All right, but I'm pretty busy. Unless, of course, you can find someone else to do the design work..." Don't you dare, is all I can think.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

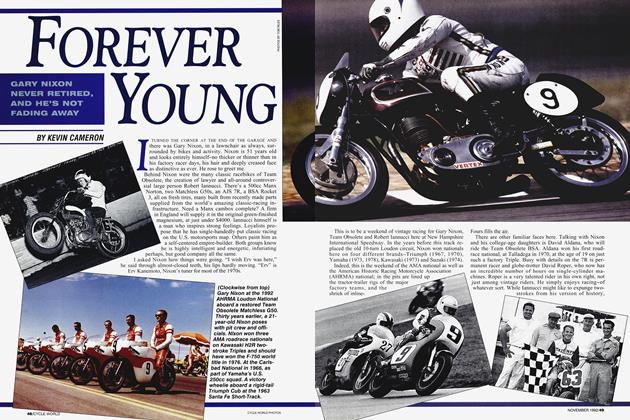

Up Front

Up FrontGeneral Stupidity

January 1999 By David Edwards -

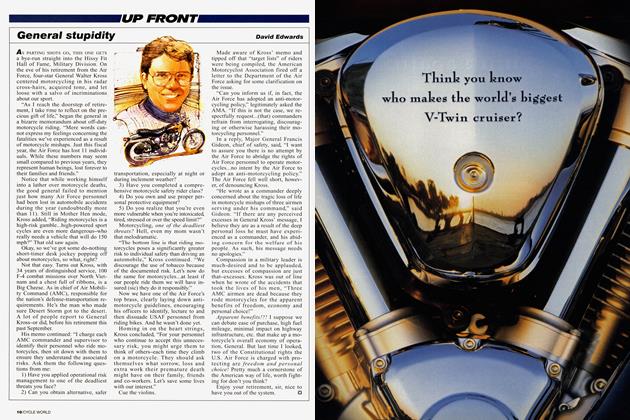

Leanings

LeaningsPaperweights of the Gods

January 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHot Oil Massage

January 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

January 1999 -

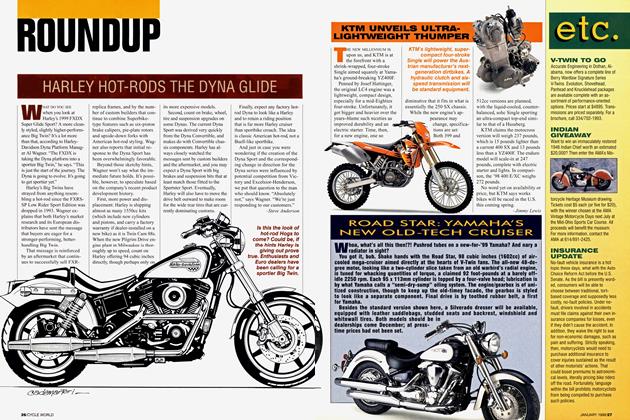

Roundup

RoundupHarley Hot-Rods the Dyna Glide

January 1999 By Steve Anderson -

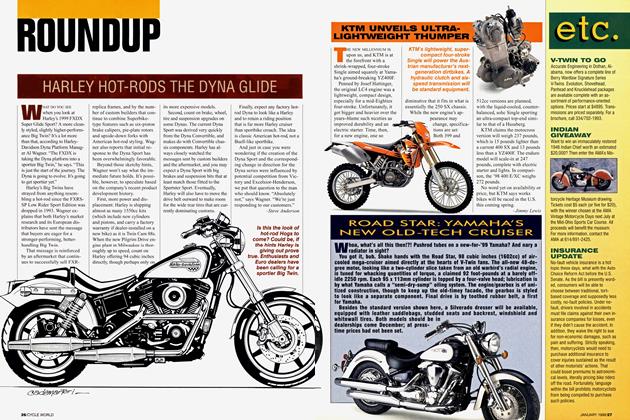

Roundup

RoundupKtm Unveils Ultralightweight Thumper

January 1999 By Jimmy Lewis