UJM redux?

UP FRONT

David Edwards

SO, THE UNIVERSAL JAPANESE MOTORcycle is dead, eh?

Readers of particularly pachyderm recall may remember the saga of my 1982 Seca 650, a UJM from the shaftdriven, Euro-styled side of the clan. Bought new, it made the trip out west with me in ’83 when I was hired by Cycle News. A year later came the call from Cycle World. Relegated to bench-warmer status by my steady diet of new testbikes, and unhappy stored in the salty air next to the Pacific Ocean, the Yamaha was giftwrapped and delivered to my dad as a Christmas present in ’85. After his death a year later, my good friend Chuck Davis took possession.

Four years on, having introduced Chuck to the joys of riding, the Seca was put on the block to make room for an ST 1100 sport-tourer. I was offered first refusal and, of course, bought the bike back, purchase price a friendly $1 per cc. Not long after, Uncle Joe Minton, then a CWcontributing editor, drafted the Yamaha as donor bike for April, 1991 ’s “Saving Old Standards: A lesson in low-cost motorcycling,” where it received all the usual Minton mod-cons: fork springs, drilled discs, braided brake lines, fork brace, etc. Early on, I’d replaced the stock shocks with an outrageously expensive set of Öhlins piggybacks; they stayed put (still there now, having been treated to fresh oil and a general going-over by the suspension specialists at Fineline Motosports, which brings to mind the old adage that $90 dress shoes last half as long as $180 shoes, but $360 shoes will last a lifetime).

When last we saw the Seca in Cycle World, it was being unceremoniously flung down the road in December, 1996’s “The 1000-Mile Ride: Cheap thrills on staff bikes,” after a thorough caning by Executive Editor B.R. Catterson on a gravelly backcountry boulevard. Brian made good on repairs, and the Yamaha, closing in on 30,000 miles, once again stood station in my garage, ready for the occasional outing or loan to out-of-town friends in need of a ride.

Which brings us to the present. My girlfriend’s old RX-7 Mazda recently burned to the waterline courtesy a wiring-loom fire, so she’s borrowing my faithful, 80,000-mile Chevy pickup. CW's long-term fleet was down to the nubs, either wrapped-up and returned to sender or out of action for repairs. And the locust swarm of ’99model testbikes had yet to descend upon the offices, so there I was w ithout a regular ride. A few psi squirted into the Metzelers, though, some extra electrons waved at the 650’s battery and baddabing-baddaboom we got wheels.

The Seca’s riding position-low-rise handlebar, mildly rearset pegs, flat, well-padded saddle-feels as good to me now as it did when I first climbed aboard 16 years ago, far better than the Queen Julianna sit-up-and-beg stance most cruisers dictate, and equally more appealing than the ’nad-crunching severity of serious sportbikes. With an old BMW tankbag strapped on, the Yamaha makes an excellent commuter, a great backroad weekender and a passable solo cross-country tourer (as it has on two occasions).

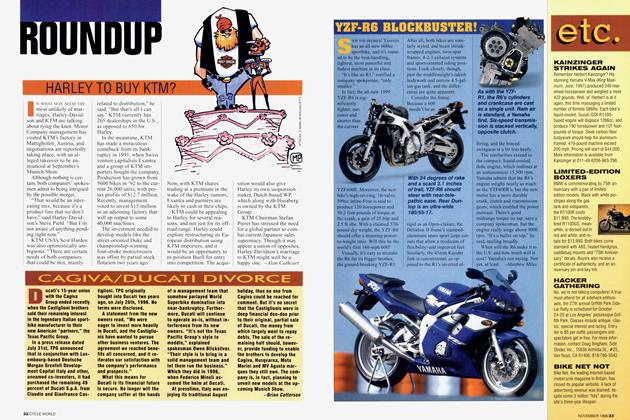

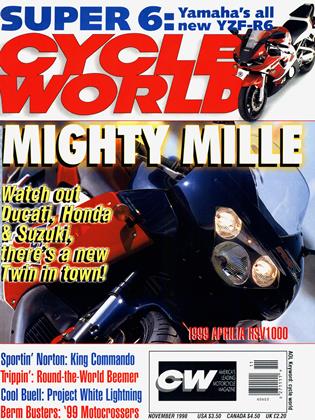

Anyway, the Seca delivers me to work last week, and there in my IN basket is news that Kawasaki will indeed sell its ZRX 1100 in the U.S. next year (see Roundup, this issue). Just in case you missed last December's “Jolly Green” riding impression, the ZRX is just like my Seca, only with twice the horsepower and torque, a fully adjustable cartridge fork, six-piston brakes, wide, radial rubber, a sexy little bikini fairing and a knockout, neon-green paint job. The Mac Daddy of Universal Japanese Motorcycles in other words, which can trace its roots back through the Eddie Lawson Replica of 1982 and the rest of the KZ1000 inline-Fours all the way to the mighty 903cc Z-l of 1973, itself an answer to that aboriginal UJM, Elonda’s 1969 CB750 Four.

And yet while the ZRX celebrates its own history, it refuses to wallow in the past as previous UJM revivals have (Kawasaki Zephyr 1100, Honda CB1000). Retro styling is all well and good, but most riders don’t want retro performance or retro handling to go along with it. That shouldn't be a problem with the Kawasaki. To illustrate the point, let’s do a quick thumbnail comparison with one of the most advanced models on the market, BMW’s new-for-1999 RUOOS, last month’s coverbike and a pretty impressive piece, almost sure to be in the running for a Cycle World Ten Best Bikes award when we cast votes next July.

BMW’s 1100 weighs-in at 513 pounds dry; Kawasaki’s scales just 3 pounds more. The Beemer’s motor, BMW’s most powerful flat-Twin yet, cranks out a fun-to-flog 87 horsepower; the Kawasaki’s retuned Ninja mill lays down a stouter 95 bhp. Torque? Try 65 foot-pounds for the S, 70 for the ZRX. The pride of Bavaria scampers through the quarter-mile in 11.82 seconds; the Kawi has it covered with an 11.09-second run. Flat-out past the radar gun, the BMW notches a 139-mph top speed; the Kawasaki ups that with a 143-mph blast. When it comes to topgear roll-ons, the 1100S goes from 4060 mph in 3.7 seconds and from 60-80 in 4.0; the ZRX waxes that with a 4060 mph time of 2.9 seconds, 60-80 of 3.0. Not that the Beemer should feel particularly bad about the latter drubbing-when it comes to roll-ons, not much short of a YZF-R1 betters the supposedly stone-ax ZRX. “Snap the throttle open and the big ZRX hurls itself down the road, sucking up asphalt at an amazing rate,” we wrote about the Kawasaki’s ability to dispatch dawdlers. “This thing doesn't just pass other vehicles, it vaporizes them.” All this for what I’d guess to be a $7199 price tag, compared to the base, nonABS RllOOS’s $13,900.

To paraphrase that great Southern philosopher Darrell Waltrip, they may not have thrown quite enough dirt on the ol’ UJM’s grave. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue