MONEY MACHINES

Japanese autoracing: Road Warrior meets the Kentucky Derby

YOKO TOGASHI

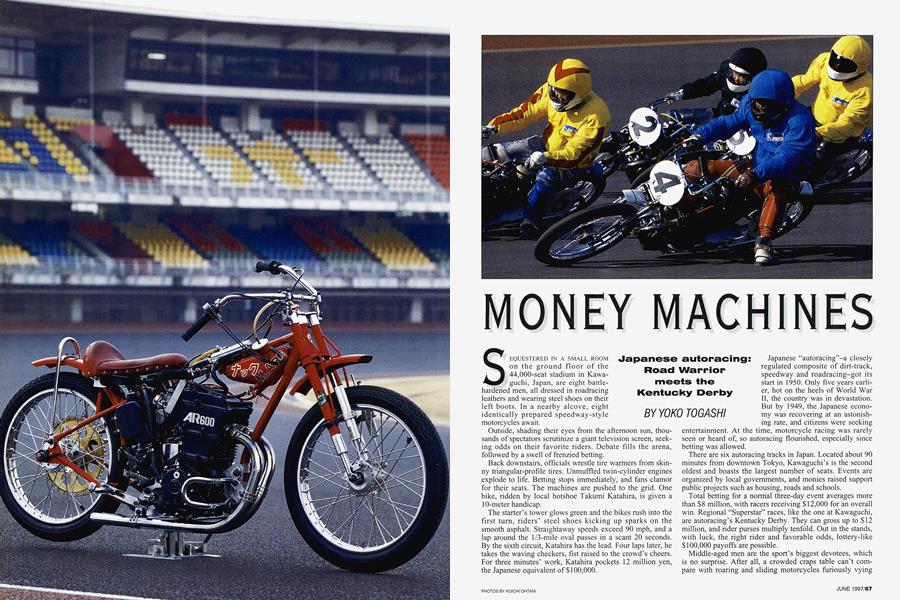

SEQUESTERED IN A SMALL ROOM on the ground floor of the 44,000-seat stadium in Kawaguchi, Japan, are eight battlehardened men, all dressed in roadracing leathers and wearing steel shoes on their left boots. In a nearby alcove, eight identically prepared speedway-style motorcycles await.

Outside, shading their eyes from the afternoon sun, thousands of spectators scrutinize a giant television screen, seeking odds on their favorite riders. Debate fills the arena, followed by a swell of frenzied betting.

Back downstairs, officials wrestle tire warmers from skinny triangular-profile tires. Unmuffled twin-cylinder engines explode to life. Betting stops immediately, and fans clamor for their seats. The machines are pushed to the grid. One bike, ridden by local hotshoe Takumi Katahira, is given a 10-meter handicap.

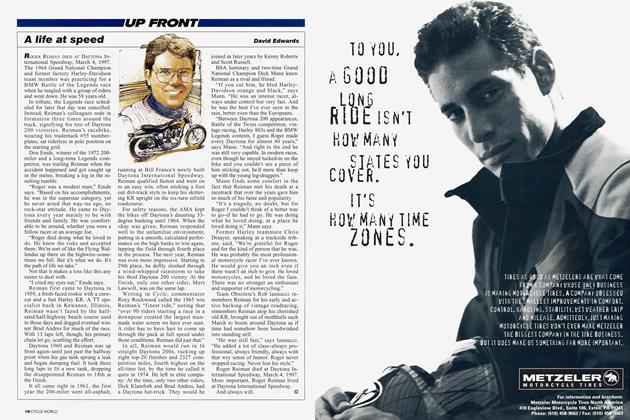

The starter’s tower glows green and the bikes rush into the first turn, riders’ steel shoes kicking up sparks on the smooth asphalt. Straightaway speeds exceed 90 mph, and a lap around the 1/3-mile oval passes in a scant 20 seconds. By the sixth circuit, Katahira has the lead. Four laps later, he takes the waving checkers, fist raised to the crowd’s cheers. For three minutes’ work, Katahira pockets 12 million yen, the Japanese equivalent of $100,000.

Japanese “autoracing”-a closely regulated composite of dirt-track, speedway and roadracing-got its start in 1950. Only five years earlier, hot on the heels of World War II, the country was in devastation. But by 1949, the Japanese economy was recovering at an astonishing rate, and citizens were seeking entertainment. At the time, motorcycle racing was rarely seen or heard of, so autoracing flourished, especially since betting was allowed.

There are six autoracing tracks in Japan. Located about 90 minutes from downtown Tokyo, Kawaguchi’s is the second oldest and boasts the largest number of seats. Events are organized by local governments, and monies raised support public projects such as housing, roads and schools.

Total betting for a normal three-day event averages more than $8 million, with racers receiving $12,000 for an overall win. Regional “Superstar” races, like the one at Kawaguchi, are autoracing’s Kentucky Derby. They can gross up to $12 million, and rider purses multiply tenfold. Out in the stands, with luck, the right rider and favorable odds, lottery-like $100,000 payoffs are possible.

Middle-aged men are the sport’s biggest devotees, which is no surprise. After all, a crowded craps table can’t compare with roaring and sliding motorcycles furiously vying

for the same scrap of asphalt. There’s a strong female following, too, which should increase exponentially when Katsuyuki Mori, ex-member of the Japanese pop-music group SMAP, makes his autoracing debut later this year.

Becoming an autoracer isn’t easy. You must be at least 17 years of age, no taller than 5-foot-10 and weigh less than 132 pounds. A motorcycle license is a must, as is good eyesight. Testing consists of three parts: a written examination, a physical and an oral interview. Some 700 hopefuls apply biennially, but only 30 make the grade. Complete the course, and you’ll spend the next six months learning to ride, race and maintain your machine.

Most are lured to the sport by money. Last year, the top autoracer earned $1 million. The average annual income is a staggering $300,000; even first-year riders take home $83,000. Forty-year-old Yukio Iwata, one of the Funbashi circuit’s top riders, made $580,000 last year. “I like roadracing and I enjoy riding my Honda CBR600F,” he says. “But autorace is the best way to earn money.”

Mitsuo Abe, a three-decade autorace veteran and father of grand prix star Norifumi Abe, was a motocrosser before switching to autorace. “One day, my team boss applied for my autoracer’s test without telling me. At the time, you could not earn very much in motocross or roadracing. I want Norifumi to become an autoracer because he can race

for a long time and earn good money, but he wants to be 500cc World Champion. He’s 21 now, and I don’t know what he’ll do when he’s 30. But it’s his life.

“I like autoracing because the race distance is very short,” Abe continues. “It helps to keep me motivated. I also like the fairness of autoracing. When I was racing motocross, I was always at a machine disadvantage, and that was really frustrating.”

In the ’50s, autoracers were powered by ohv Triumph Twins.When those wore out, Meguro-later bought-out by Kawasaki-supplied replica engines, and automotive turbomaker HKS also dabbled in the sport. These days, autoracers still ride simple, tubeframed machines propelled by air-cooled parallel-Twins. Designed and manufactured by Suzuki, the current engines displace 599cc and have separate clutches and twospeed gearboxes. Peak output is 59 horsepower at 8000 rpm. Maximum torque is 45 foot-pounds at 6000 rpm.

Up front, skinny inverted forks employ twin steering dampers in lieu of traditional damper rods. Rear ends are rigid, and there are no brakes, front or rear. Tiny gas tanks hold a half-gallon of fuel. Purpose-built Dunlop KR73s are shaved to reduce tread squirm, then regrooved.

Since autoracers turn left exclusively, handlebars are configured for greater machine control. The left half of the bar is angled up to clear the riders’ knees while the right half droops down, clubman-style,

CORNERING SPEEDS ARE MUCH HIGHER THAN DIRT-TRACK BECAUSE WE HAVE BETTER GRIP. BUT THE BASIC TECHNIQUE IS THE SAME: SLIDE THE FRONT FIRST, THEN THE REAR.”

parallel to the lower frame tube.

Another innovation is the “knee gripper.” This foam-covered rod juts out from the right side of the frame at a 90degree angle to the engine, providing a place for the rider to secure himself to the machine should the tires slide. “Cornering speeds are much higher (than dirt-track) because we have better grip,” says Abe, “but the basic technique is the same. The best technique is to slide the front first, then the rear. Katahira is very good at this.”

With substantial sums at stake, the bikes are subject to strict guidelines. Except for crankcase rebuilds, competitors must perform their own maintenance. Engine modifications are limited to carburetor jetting, and ignition and valve timing-no porting, cheater camshafts or special CDI boxes are allowed. Gearing is fixed. Pre-race,

engines are sealed to prevent tampering. Post-race, bikes are chosen at random, tom down and inspected.

Because tuning is so limited, little things, such as valve-

spring tension, play an important role. “We change (valve springs) every two or three races,” Abe says. “Peak power is the same, but acceleration is better.” Penalties for cheating are severe. Cross the white line that rings the inside of the racetrack, for example, and you’re disqualified. Dispute the penalty and officials decide the case using videotape. Kicking and pushing aren’t tolerated, either. Get caught and you’ll be suspended for three days.

Pre-race rules even extend to outside communication. Competitors must

arrive one day prior to race day, and stay in a hotel adjacent to the stadium. They cannot make phone calls, even to family members, or venture outside to buy a sandwich or a beer.

Justifying these rigid guidelines is easy. After all, autorace has its skeletons. In the mid-’60s, Japanese Mafia involvement ended in several rider sackings. Never again, arrowstraight officials avow.

Nonetheless, autoracing, as with any form of organized gambling, exists for a single reason: to spawn revenue. Lots and lots of revenue. In the Elollywood box-office smash Jerry Maguire, Cuba Gooding Jr.’s character is fond of shouting, “Show me the money!”

Autorace fans and competitors know exactly what he means. □

A broadcaster, translator and writer, Yoko Togashi has authored eight books, including The Legend of Pops Yoshimura.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue