SUPERSPORT EVOLUTION

WADING INTO THE 600cc GENE POOL

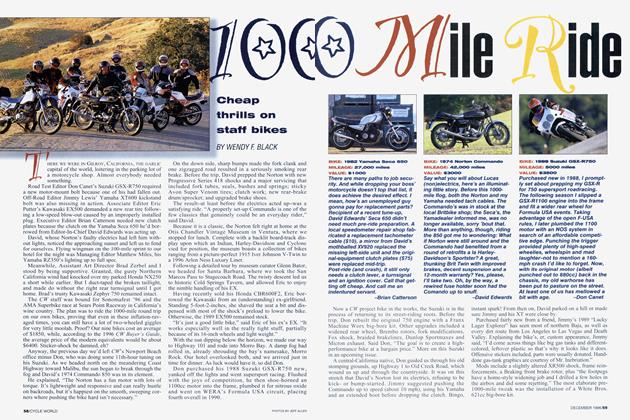

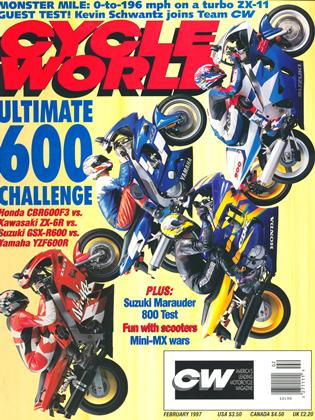

THE 600cc SPORTBIKE IS THE hottest ticket in town. Accounting for almost 40 percent of total U.S. sportbike sales, 600s promise performance and speed galore, but are less intimidating and less costly than their largerdisplacement brethren.

Strange, then, that such a popular motorcycle segment is so young, tracing its family tree back just 16 years. Even more peculiar is the fact that the 600s' development began with a bike that wasn't even a 600.

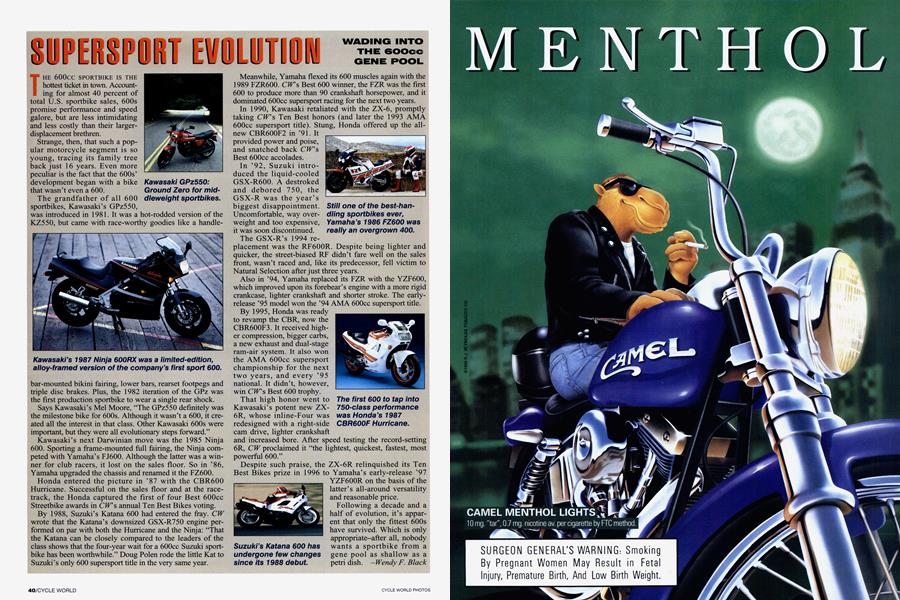

The grandfather of all 600 sportbikes, Kawasaki's GPz55O, was introduced in 1981. It was a hot-rodded version of the KZ550, but came with race-worthy goodies like a handlebar-mounted bikini fairing, lower bars, rearset footpegs and triple disc brakes. Plus, the 1982 iteration of the GPz was the first production sportbike to wear a single rear shock.

Says Kawasaki's Mel Moore, "The GPz55O definitely was the milestone bike for 600s. Although it wasn't a 600, it cre ated all the interest in that class. Other Kawasaki 600s were important, but they were all evolutionary steps forward."

Kawasaki's next Darwinian move was the 1985 Ninja 600. Sporting a frame-mounted full fairing, the Ninja com peted with Yamaha's FJ600. Although the latter was a win ner for club racers, it lost on the sales floor. So in `86, Yamaha upgraded the chassis and renamed it the FZ600.

Honda entered the picture in `87 with the CBR600 Hurricane. Successful on the sales floor and at the race track, the Honda captured the first of four Best 600cc Streetbike awards in CW's annual Ten Best Bikes voting.

By 1988, Suzuki's Katana 600 had entered the fray. CW wrote that the Katana's downsized GSX-R750 engine per formed on par with both the Hurricane and the Ninja: "That the Katana can be closely compared to the leaders of the class shows that the four-year wait for a 600cc Suzuki sportbike has been worthwhile." Doug Polen rode the little Kat to Suzuki's only 600 supersport title in the very same year.

Meanwhile, Yamaha flexed its 600 muscles again with the 1989 FZR600. CW's Best 600 winner, the FZR was the first 600 to produce more than 90 crankshaft horsepower, and it dominated 600cc supersport racing for the next two years.

In 1990, Kawasaki retaliated with the ZX-6, promptly taking CW's Ten Best honors (and later the 1993 AMA 600cc supersport title). Stung, Honda offered up the all new CBR600F2 in `91. It ________________________ provided power and poise, and snatched back CW's Best 600cc accolades.

In `92, Suzuki intro duced the liquid-cooled GSX-R600. A destroked and debored 750, the GSX-R was the year's biggest disappointment. Uncomfortable, way over weight and too expensive, it was soon discontinued.

The GSX-R's 1994 re placement was the RF600R. Despite being lighter and quicker, the street-biased RF didn't fare well on the sales front, wasn't raced and, like its predecessor, fell victim to Natural Selection after just three years.

Also in `94, Yamaha replaced its FZR with the YZF600, which improved upon its forebear's engine with a more rigid crankcase, lighter crankshaft and shorter stroke. The early release `95 model won the `94 AMA 600cc supersport title.

By 1995, Honda was ready to revamp the CBR, now the CBR600F3. It received high er compression, bigger carbs, a new exhaust and dual-stage ram-air system. It also won the AMA 600cc supersport championship for the next two years, and every `95 national. It didn't, however, win CW's Best 600 trophy.

• • ht high honor went to Kawasaki's potent new ZX 6R, whose inline-Four was redesigned with a right-side cam drive, lighter crankshaft and increased bore. After speed testing the record-setting 6R, CW proclaimed it "the lightest, quickest, fastest, most owerfu1 600."

Despite such praise, the ZX-6R relinquished its Ten Best Bikes prize in 1996 to Yamaha's early-release `97 YZF600R on the basis of the latter's all-around versatility and reasonable price.

Following a decade and a half of evolution, it's appar ent that only the fittest 600s have survived. Which is only appropriate-after all, nobody wants a sportbike from a gene pool as shallow as a petri dish.

Wendy F. Black

View Full Issue

View Full Issue