A CHANGING OF THE GUARD

HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE FOR A REVOlutionary force to overthrow the status quo and establish a new order?

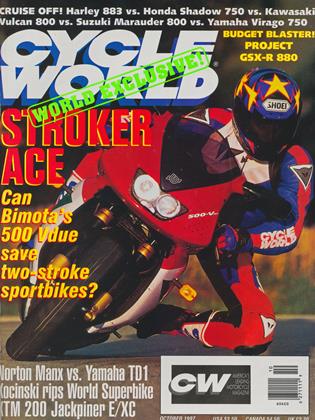

Forget e-mailing bearded old Fidel Castro for the answer to this one. Instead, point your nostalgia browsers to roadracing, where revolution required precisely the amount of time it took for a piston in a 125cc cylinder, paired with another one exactly the same size, to complete a two-stroke power cycle at 11,000 rpm. Up and down once, a single crankshaft revolution timed to the beat of a hummingbird's wing. With that, the old order of top-echelon championship roadracing-in place since before the first running of the Isle of Man TT in 1907-began to crumble.

The successful and reliable completion of that power cycle wasn’t easy. But when finally it was accomplished, it changed the face of racing and caused racers everywhere-those who worshiped at the altar of the Norton, MV, Honda, Ducati or AJS/Matchless fourstroke engine-to convert to a new religion.

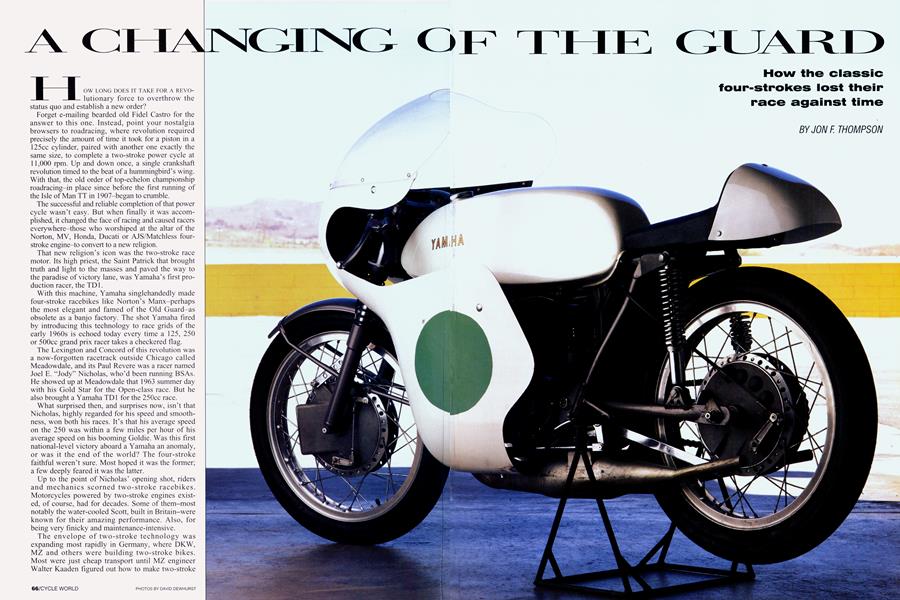

That new religion’s icon was the two-stroke race motor. Its high priest, the Saint Patrick that brought truth and light to the masses and paved the way to the paradise of victory lane, was Yamaha’s first production racer, the TD1.

With this machine, Yamaha singlehandedly made four-stroke racebikes like Norton’s Manx-perhaps the most elegant and famed of the Old Guard-as obsolete as a banjo factory. The shot Yamaha fired by introducing this technology to race grids of the early 1960s is echoed today every time a 125, 250 or 500cc grand prix racer takes a checkered flag.

The Lexington and Concord of this revolution was a now-forgotten racetrack outside Chicago called Meadowdale, and its Paul Revere was a racer named Joel E. “Jody” Nicholas, who’d been running BSAs. He showed up at Meadowdale that 1963 summer day with his Gold Star for the Open-class race. But he also brought a Yamaha TD1 for the 250cc race.

What surprised then, and surprises now, isn’t that Nicholas, highly regarded for his speed and smoothness, won both his races. It’s that his average speed on the 250 was within a few miles per hour of his average speed on his booming Goldie. Was this first national-level victory aboard a Yamaha an anomaly, or was it the end of the world? The four-stroke faithful weren’t sure. Most hoped it was the former; a few deeply feared it was the latter.

Up to the point of Nicholas’ opening shot, riders and mechanics scorned two-stroke racebikes. Motorcycles powered by two-stroke engines existed, of course, had for decades. Some of them-most notably the water-cooled Scott, built in Britain-were known for their amazing performance. Also, for being very finicky and maintenance-intensive.

The envelope of two-stroke technology was expanding most rapidly in Germany, where DKW, MZ and others were building two-stroke bikes. Most were just cheap transport until MZ engineer Walter Kaaden figured out how to make two-stroke

How the classic four-strokes lost their race against time

JON F. THOMPSON

engines both powerful and relatively reliable. Kaaden solved several problems, including these two: l) How to make the two-stroke breathe effectively; and 2) how to match the piston’s expansion rate-ferocious because it was exposed to the heat of‘combustion on every cycle-to that of

the cylinder. His success meant that suddenly a two-stroke could reliably fire twice as often as a four-stroke turning the same rpm, and flow much more air-fuel mixture with fewer frictional losses. This translated to more horsepower per cubic centimeter, and was good for MZ. It was bad for the rest of the world because, at first, sanctioning bodies didn’t discriminate between engine types. They lumped 250cc two-strokes, for instance, into the same class with 250cc four-strokes. And why not? To that point, two-strokes displayed no appreciable advantage over the established order.

MZ racer Ernst Degner was the on-track beneficiary of Kaaden’s work. When he defected from East Germany’s Communist regime to the West, he took elements of Kaaden’s two-stroke horsepower and reliability formulae with him. Degner landed a ride with Suzuki, which immediately began fielding some surprising little two-stroke racebikes.

Maybe what Degner did was immoral and unethical, maybe it wasn’t. Maybe Suzuki shared its new technology with other manufacturers, maybe it didn’t. In any case, it didn’t take long for Yamaha to figure out how to make twostrokes work. A wide array of successful designs followed. One of them was the YDS3, a 250cc Twin streetbike. It was that design which Yamaha developed into the TD1.

Roadracers in the early 1960s came from Norton, BSA and AJS/Matchless in Britain; or from Ducati, Parilia and Aermacchi in Italy; or from Harley-Davidson in America. A few were production racers. Most were streetbikes tuned to race-readiness. All were big, heavy four-strokes, most were Singles. They were as predictable and reliable as Grandma’s Sunday roast beef. All were caught absolutely flat-footed by Nicholas and his Yamaha that day at Meadowdale.

Nicholas remembers his first ride on a TD1: “It didn’t take me long to realize that this was one quick puppy. It was very small and very pipey; it didn’t have a smooth transition from not running at all, to wailing down the road, blowingoff everything else. Get it to 8000 rpm and it just lit up, and you’d go through the gears as quick as you could pull in the clutch lever. It didn’t handle particularly well, but there was no reason to push it, not at first. Why scratch around comers when you had 20 miles per hour on everybody else down the straights?”

Phil Schilling, former editor of Cycle and noted Ducati tuner, was in the paddock that day at Meadowdale. He says of Nicholas’ performance on the TD1, “I was afraid of what this meant. And as we got into 1964, it became clear what

we were up against, as more and more of the Yamahas were running well. And by 1965, we just had to say, ‘Well, that’s the way it’s going to be,’ and begin planning to switch over to these things.”

Many made the switch reluctantly, as two-strokes were equated with cheapness, and with trouble. Schilling adds, “They were unreliable. Most people thought the place for them was on a chainsaw.”

Their cooling problems meant that two-stroke engines would seize, a piston expanding so greatly that it welded itself to its own cylinder wall.

Says Schilling, “They tended to seize going into a corner when you were getting off the gas, shutting off their (oilin-gas) lubrication. And when that happened you were in real trouble,” because seizure meant that the rear wheel locked solid.

This, along with exhaust tuning, was a part of the problem that Kaaden had worked on, and Yamaha added to his work by attacking on two fronts. The first involved additional metallurgy aimed at allowing the super-heated piston and its cylinder to expand at similar rates. The second involved careful coatings on the cylinder walls.

The company’s first effort, the TD1A, used cylinder barrels with anodized walls. This proved not a successful choice. But the TD1 A’s problems were greatly minimized in the TD1B. It got chrome-plated cylinder bores and other important upgrades.

The bike came with a manual that advised the owner how to break-in the engine. This included detailed instructions on piston inspection, and on removal of high spots on piston walls with sandpaper.

Says Schilling of these procedures, “Well, this was like getting ready for a space shot. We’d have our little Ducatis together for three or four races before we even bothered to look at them, and here you were yanking barrels and sanding pistons. And you didn’t have any choice. You either learned to do this or you weren’t going to be competitive.”

Tony Murphy, who began racing TDls in 1963, recalls that for all Yamaha’s development work, they were far from bulletproof: “We had what we used to call the ‘two-stroke twitch.’ You always had a couple of fingers on the clutch because you never knew when they were going to seize.”

Fingers on the clutch? That might not help. TD1 expert Jim Merz says seizure-even on a properly prepared TDIB-can be almost instantaneous: “Maybe your brain gets the message that it’s about to happen, but it happens so quickly that you can’t do anything about it.”

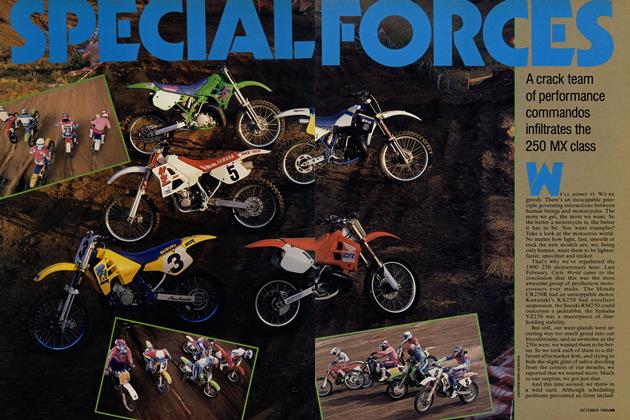

It is Merz’s TD1B that Don Vesco, Nicholas and Murphy rode for Cycle World-along with Vesco’s Team Obsolete Manx-as they reacquainted themselves with these watershed bikes for this story.

Tuners and riders soon figured out the TD1B, to the horror of the Old Guard. Murphy recalls, “We went to Daytona-me, Vesco, Dick Mann and Gary Nixon-in 1964, and they (the other runners in the 250cc roadrace) didn’t know which way we went.”

Small wonder. The Open-class bikes-the Manxes and Triumphs and BSAs-were clocking top speeds of 133 mph, maybe 134 mph on Daytona’s banking. The 250cc Yamahas were doing 131 mph. The 250cc Parillas, Ducatis and Harley Sprints, which maybe crawled to 120 mph, didn’t have a chance.

Vesco recalls 1965 at Daytona, when the 250 race’s 103 starting positions supposedly were drawn from a hat. “The whole front row was orange and black,” Vesco now says with a grin, “and us guys on Yamahas-Tony, Ron Grant and me-were in positions 101, 102 and 103. We raced AFM

those days, and that was the AMA telling us where we belonged. I remember Tony said, ‘Let’s just take it easy,’ and then the flag dropped. I went into the grass, passed everybody, and had the lead when we came down off the banking that first lap. I remember thinking, ‘This isn’t so bad. I hope Tony’s still back there relaxing.’ ”

Yamaha’s domination was so complete that soon whole race grids were made up of TDIBs, and the racing became so close that winning your club race no longer was as easy as it had been for Nicholas to win that national at Meadowdale.

Murphy, for instance, soon learned that if he merely rode his TD1B at 10/ioths, he got passed. He, and others, learned to ride at n/ioths, he says, and this exposed the TDl’s handling problems. Their small, light frames-a TD1B weighs about 230 pounds dry, compared to the 325 pounds of a Manx-allowed the bikes to flex wildly when pushed hard. Murphy says, “Ride them at Cloths, that was no problem. But if you rode them at /doths, you finished seventh, or eighth. In those days, the grids were so full of TDls that a

Yamaha would win, and a Yamaha also would be last.”

At the sharp end of the field, where the fast guys were riding at n/ioths, Nicholas remembers, “You’d have a chain of wobblers, with everyone wobbling at the same frequency. You just learned to let them leap around between your legs.” Learning to ride TDls ultimately meant revising a lot of habits and procedures. Sure, you took your TD1B out of its

crate, bolted on Girling shocks and sticky tires, and went racing. But where you did no more than change your Manx’s oil, check your Ducati’s desmo valve clearances or lube your Honda’s chain after every race, perhaps inspecting piston and rings at the end of every season, you did much more than that to a Yamaha every time you ran it.

First, there was the clutch. After every hot start you deglazed the friction plates and replaced the cracked or burned steel plates. After every race, you’d pull the head and cylinders to check piston clearance. Every time you ran the engine, its crude magneto-and-points ignition had to be retimed because the points-rubbing block wore so rapidly.

Indeed, at the end of our nostalgic morning at Willow Springs, after Nicholas, Murphy and Vesco each had turned their reacquaintance laps on the bikes you see in these photos, the Manx still ran as strongly as ever, and the TD1B had fried its clutch.

In the end, says Nicholas, the fantastic success of the fragile little Yamahas was due as much to the British as it was to the Japanese. He says, “The English were reluctant to try anything new or radical or different. The Japanese were apt to start with something brand new. They didn’t have any fear of spending money on development. The British were terrified of that. They had to make the books balance, or they couldn’t do the project.”

And thus was lost a way of life, one in which one man designed and built racebikes intended to endure. In the 1950s, for instance, you knew that your Manx was the work of Joe Craig in the Norton factory, just as surely as you knew that your AJS 7R, or your Matchless G50, was the result of everything Jack Williams learned during his long tenure with Associated Motor Cycles, Ltd., which manufactured both makes.

Recalls Murphy, “With the Japanese stuff, you couldn’t put your finger on who designed or built them; it was a committee sort of thing. When one man’s doing it, he’s got his fingers in everything. I kind of felt that at Yamaha the guys who made the engine didn’t know the guys who made the frame, and those guys didn’t know the guys who did the brakes. As a result, the bike wasn’t a unit, it was just bits and pieces bolted together.”

Effective bits and pieces, though, were those Yamahas and their spawn. By the time Nicholas’ TDl rolled onto the grid at Meadowdale, you couldn’t make a Manx, for instance, or a Ducati, much faster than it already was; such bikes, and the engines that powered them, were nearing the end of their development cycles. But Yamaha followed the TDIB with the TD2, which was faster and more reliable than its predecessor. Then it built the TR2B, an air-cooled 350 that was faster and more reliable than its predecessors. Then came the TD3, and TR3s and the TA250s-all faster and more reliable than their predecessors. Then Yamaha unleashed the liquid-cooled TZ250 and 350, which were faster and more reliable still.

Racer and four-stroke stalwart Jess Thomas recalls, “When they got the water-cooled ones, wow, you’d just better throw in the towel after that.”

Sanctioning bodies soon learned that the only way to keep Yamaha two-strokes from dominating was to exclude them. Some believe that factor helped allow Ducati’s 1972 Imola win, the event that put the Italian marque and its fabled 750 Super Sport on the map. But the next year, 1973, Yamaha 350s were allowed to race at Imola, and Finn Jamo Saarinen used one to blow everybody else’s doors off. Yamaha was on a roll. What followed, along with TZ700s, TZ750s, and YZR250s and 500s, were most other factory race departments. As a result, when you go to a grand prix today, the powerplants you see and hear are two-strokes.

Racebikes like Norton’s hallowed Manx, meanwhile, weren’t instantly obsolete. Big four-stroke Singles and Twins continued with occasional wins through the mid1970s. Eventually, however, such bikes became ready-made vintage racers.

Tony Murphy, Jody Nicholas, Don Vesco-they couldn’t have known that they, and racers like them, were soldiers in a revolution, their TDIBs the cannons and swords of that revolution. Nevertheless, their bikes changed the face of racing. They helped bring about a changing of the guard. You can bet your last Cuban peso on it. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontPlan 2003

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsParking Lot At Assen

October 1997 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCReally Nice Racebikese

October 1997 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1997 -

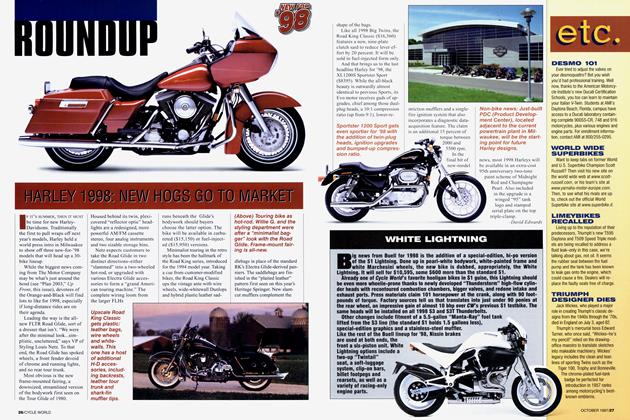

Roundup

RoundupHarley 1998: New Hogs Go To Market

October 1997 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupWhite Lightning

October 1997