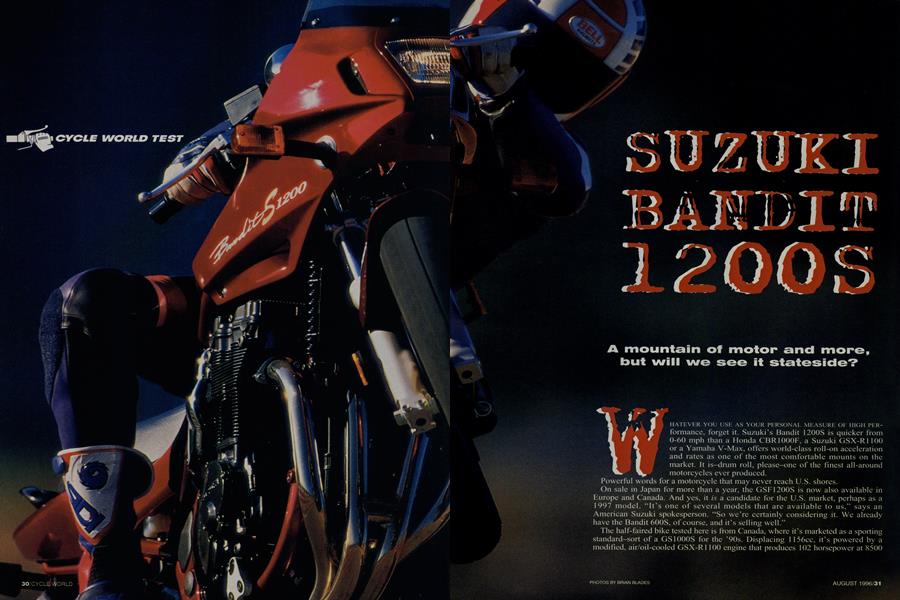

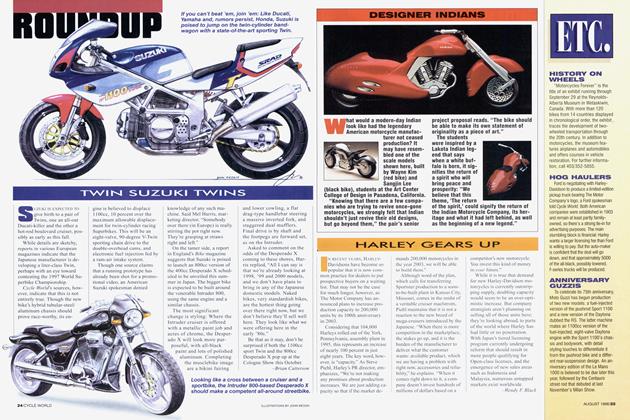

CYCLE WORLD TEST

SUSUKI BANDIT 1200S

A mountain of motor and more, but will we see it stateside?

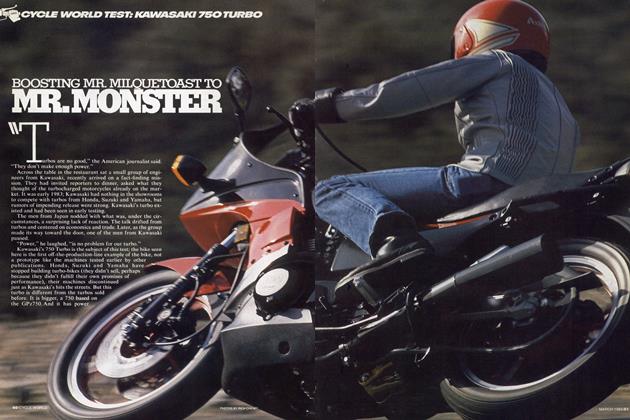

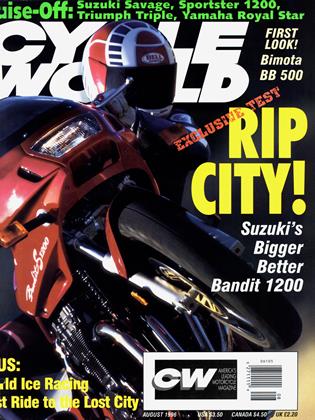

WHATEVER YOU USE AS YOUR PERSONAL MEASURE OF HIGH PERformance, forget it. Suzuki's Bandit 1200S is quicker from 0-60 mph than a Honda CBR1000F, a Suzuki GSX-R1100 or a Yamaha V-Max, offers world-class roll-on acceleration and rates as one of the most comfortable mounts on the market. It is—drum roll, please—one of the finest all-around motorcycles ever produced. Powerful words for a motorcycle that may never reach U.S. shores. On sale in Japan for more than a year, the GSF1200S is now also available in Europe and Canada. And yes, it is a candidate for the U.S. market, perhaps as a 1997 model. "It's one of several models that are available to us," says an American Suzuki spokesperson. "So we're certainly considering it. We already have the Bandit 600S, of course, and it's selling well." The haif-faired bike tested here is from Canada, where it's marketed as a sporting standard-sort of a (iS 1000S for the '90s. Displacing 1156cc, it's powered by a modified, air/oil-cooled GSX-R 1100 engine that produces 102 horsepower at 8500

rpm. That’s 21 ponies less than the newgeneration, liquid-cooled GSX-R, but you’ll never miss ’em, because peak torque, all 70 foot-pounds of it, comes much sooner, at 6250 rpm. More importantly, 94 percent of that sum is available way down at 3250 rpm, which, despite taller final gearing, translates into extraordinary top-gear roll-on numbers.

Still not convinced? Well, consider this: The 490-pound 1200S accelerates from 40-60 mph in just 3.0 seconds, while 60-80 mph comes in a mere 2.9 seconds. Only Triumph’s torque-intensive Trophy 1200 and Honda’s lightweight CBR900RR produce comparable numbers. Kawasaki’s ZX-11?

No contest. Even the $23,000, GSXR1 1 00-powered Bimota SB6 can’t match the Bandit’s roll-on acceleration.

To achieve that stump-pulling performance, Suzuki increased the GSX-R motor’s cylinder bore by 1mm, selected flat-top pistons that reduce compression to 9.5:1, juggled camshaft and ignition timing, and fitted 36mm CV carburetors in place of the usual 40mm mixers.

Shims gave way to threaded valve-lash

adjusters, even though maintenance intervals remain the same. Airbox volume is down, and the frame-mounted oil cooler is slightly smaller. The racy stainless-steel and aluminum 4-into-l exhaust system is also new-and exceptionally quiet. Combustion chamber volume, piston height, ring shape, valve sizes, crankshaft dimensions and internal transmission ratios are unchanged from oldstyle GSX-R 1100s.

The twin-cam inline-Four warms quickly (unlike some GSX-Rs we’ve tested), and response throughout the entire powerband is outstanding. The engine answers to the throttle from as low as 1500 rpm, with arm-straightening pickup above 4 grand. Snap the throttle open in first gear and the front wheel levitates skyward-no clutching or handlebar yanking needed here. With gobs of torque on tap, the Bandit does not require frequent shifts. Even so, the five-speed transmission imparts such a feeling of mechanical precision that shifting is a real thrill. The only downside to this remarkable performance is a bit of buzziness, which is transmitted to the rider via the tubular handlebar and rubber-mounted footpegs. Fortunately, the vibration is most apparent off-throttle; going through the gears, it is barely noticeable. The small, round mirrors are not so lucky. Images are difficult to distinguish at nearly any engine speed-is that a bread truck or a state trooper coming up from behind?

Based on its engine alone, the 1200S is immediately lovable. But unlike the truckish, shaft-drive GSX1100G of a

few years ago, the bike’s handling excites, too. One clue is the chassis dimensions, which closely mimic the Bandit 600’s. Similarities between the two frames-right down to the curious press-in plastic covers located just above the swingarm pivot-are uncanny. The 1200’s main tubes are larger and have been additionally reinforced, plus the 600’s steel swingarm was replaced with a robust, box-section aluminum piece. Yet despite a taller seat height and additional overall length and width, our 1200 had a slightly shorter wheelbase than the 600 we test ed last year. The 1200's steering geometry is, however, more relaxed, with 25.6 degrees of rake (compared to the 600's 25.1) and 4.2 inches of trail (compared to 3.9 inches). There are other, equally important differences. The 1200's suspension is by Showa, rather than by Kayaba as used

on the 600. Borrowed from the RF900R, the cartridge-type fork is a conventional unit with beefy 43mm tubes and 4.1 inches of smooth travel. Screw adjusters atop both legs increase spring preload, but do not dramatically alter ride quality. The link-type rear shock absorber is also adjustable, sporting a seven-way ramped spring-preload collar and a four-position rebound-damping wheel. Progressive spring and damping rates allow the bike to swallow big jolts from speed bumps and potholes yet maintain its composure dur ing brisk cornering. Despite the bike's lack of clip-ons and full-coverage body-

work, hard chargers will not be disappointed. The wide han dlebar provides excellent leverage, and steering is nicely neutral. Admittedly, the bike doesn't possess the laser accu racy and nimble, responsive feel of a GSX-R750, for exam ple, but the Bandit nonetheless makes short work of a twisty road. Cornering clearance is excellent. The rubber-covered footpegs touch down at aggressive lean angles, but the side stand and standard-equipment centerstand are tucked well out of harm's way. Putting the power to the pavement are sticky Bridgestone Battlax BT-54R radials, which are mounted on 17-inch wheels lifted from the GSX-R1 100. Designed for sport-tour ing applications, the deeply grooved Z-rated rubber provides good feedback and traction, and appears to be long-wearing, too. RF900R-spec four-piston Nissin calipers and 12.2-inch floating rotors also give good feel-and immense stopping power. A single-finger pull on the four-way adjustable lever is enough for most situations; two fingers will lift the rear

wheel clear of the pavement. A two-piston Tokico caliper and solid-mounted 9.4-inch disc grace the rear, and also perform well. Regarding ergonomics, it's pleasing to report that the Bandit is very comfortable, whether commuting, sport riding or touring. Cockpit controls are easily within reach, par ticularly after we rotated the handlebar back slightly. The one-piece seat angles down, tilt ing the rider forward into the windblast, taking pressure off his wrists. Footpegs are moderate ly rearward-perfectly located, in other words. This combination works well, but at least one tester complained that the seat was a bit nar row up front and the foam a smidgen too soft; overall, though, a very effective and versatile riding position. Praise also goes to the nicely integrated half fairing, which offers excellent protection from the elements despite its relatively small size. Unlike the inside of the Bandit 600 fairing, which is afflicted with unsightly overspray, the 1200 fair ing's interior surfaces are painted to match the frame, fuel tank and tailsection. The chromed-plastic airbox covers carry less aesthetic appeal, however. So, we like the Bandit a lot. But one all-important ques tion remains: Will a modern big-bore standard succeed stateside? Four short years ago, Kawasaki's retro-styled ZR1 100 set the pace for the second coming of "Universal Japanese Motorcycles," or UJMs. "Few motorcycles possess the ZR's blend of `70s styling and `90s performance. Few motorcycles are this versatile and this much fun to be around," we wrote in our 1992 test of the bike. Yet despite its broad-based performance and updated brakes, suspen sion, tires and wheels, that model-and others like it, such as Honda's CB1000-sold poorly and was quickly discontin ued. Apparently, looking back was not progress. But as its appearance and performance indicate, the

Bandit 1200S is not a blast from the past; instead, it is a modern high-performance motorcycle for adults-a sophisticated, high-tech hot-rod. Nevertheless, a careful ly-worded marketing plan will prove vital if the bike is to succeed in the U.S. "We had a similar dilemma with the Bandit 600S," says an American Suzuki spokesperson. "It was clearly a standard. But we didn't emphasize cate gorizing the bike. Instead, we concentrated on its perfor mance and handling." In the recent past, labeling a motorcycle a "standard" has been the kiss of death. But if any bike can put the sizzle back in the standard, the GSF1200 is it. The Bandit offers incredible engine performance, all-day comfort, responsive handling and handsome styling. Suzuki won't comment officially, but expect a suggested retail price of about $8000 if the bike dQes come to the United States for 1997. Considering what the Bandit offers, that could easily make it the big-bike bargain of the year.

EDITORS' NOTES

IF YOU OWNED A 1979 SUZUKI GS1100E (or any versatile big-bore standard from that era), you're probably doing backflips over this Canadianspec GSF1200. The big Bandit's acceleration is on par with current literclass sportbikes. Braking is stone-wall immediate. Long-haul comfort supersedes that of many broad-based sporttourers. Handling? Superb. Trouble is,

as of presstime, American Suzuki had not committed to selling the bike in the U.S. in 1997.

Call it the Standard Stigma, the unfortunate malediction that quashed bikes like BMW’s K75, Kawasaki’s Zephyr 1100 (one of my favorites), Honda’s CB1000 and CB750, Suzuki’s VX800 and GSX1100G, and Yamaha’s weirdHarold TDM850, to name a few. Using this kindred collection as reference, it would appear American motorcycle enthusiasts are only interested in cruisers, motocrossers and sportbikes; that the modem standard is a dead horse. I, for one, hope this is not the case.

-Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

ONE OF MY VERY FIRST ASSIGNMENTS when I started at Cycle World in 1991 was to write an "Editor's Note" on a Suzuki Bandit. Now here it is, five years later, and the Bandit has doubled in cost and tripled in displacement. Is this progress? You bet it is. Both complaints I had about the Bandit 400-cramped ergonomics anda

dearth of low-end power-have been addressed on the 1200. The new bike is much more comfortable for a 6-footer like me, and its big-bore GSX-R motor makes so much lowto midrange power that you can largely ignore the shift lever.

Combined, these two traits make the Bandit a tough bike to beat for real-world riding. Sure, Open-class sportbikes possess more top-end power, but the Bandit makes the bulk of its ponies where you’ll use them every day-at the lower end of the tachometer. Let’s be realistic: What percent of the time does a GSX-R 1100 owner spend at redline, anyway? -Brian Catterson, Executive Editor

THE MOTORCYCLES THAT MADE JAPAN famous were not racetrack refugees or counterfeit Harley-Davidsons. They were fast, full-size pavement scorchers like the Honda CB750 Four, the Kawasaki Z1 and the Suzuki GS750, exciting all-around bikes that were equally at home on Route 66 or Racer Road.

Two decades after those machines burned themselves into American riders’ psyches comes the Bandit 1200, an enticing update of the UJM. More than 100 horsepower, less than 500 pounds, buckets o’ torque, contemporary brakes, suspension and tires.

For you serious bhp fiends, even more urge is as close as any Yoshimura catalog, though you’d better order up a wheelie bar at the same time. Most of us, I’d wager, would be ecstatic with the Bandit just as it comes. It’s a straightahead, no-lies machine that’s not trying to be anything other than what it is.

Which happens to be a motorcycle, pure and simple.

-David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief

SUZUKI

BANDIT 1200

View Full Issue

View Full Issue