THE ULTIMATE STONE AXE

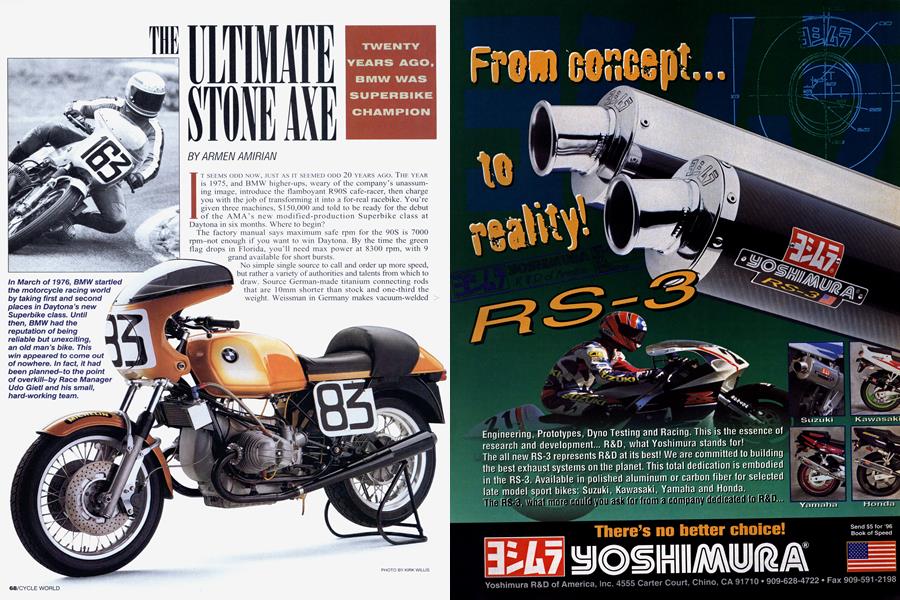

TWENTY YEARS AGO, BMW WAS SUPERBIKE CHAMPION

ARMEN AMIRIAN

IT SEEMS ODD NOW, JUST AS IT SEEMED ODD 20 YEARS AGO. THE YEAR is 1975, and BMW higher-ups, weary of the company's unassuming image, introduce the flamboyant R90S cafe-racer, then charge you with the job of transforming it into a for-real racebike. You're given three machines, $150,000 and told to be ready for the debut of the AMA's new modified-production Superbike class at Daytona in six months. Where to begin?

The factory manual says maximum safe rpm for the 90S is 7000 rpm-not enough if you want to win Daytona. By the time the green flag drops in Florida, you’ll need max power at 8300 rpm, with 9 grand available for short bursts.

No simple single source to call and order up more speed, but rather a variety of authorities and talents from which to draw. Source German-made titanium connecting rods that are 10mm shorter than stock and one-third the weight. Weissman in Germany makes vacuum-welded hollow lifters that weigh one-fifth as much as the stockers. Oscar Liebmann of AMOL Precision fabricates beautiful fluted hollow titanium pushrods (with steel ends). Venolia in California makes short pistons with wrist-pin bosses moved up 1 5mm-this, with the shorter rods, allows the cylinders to be cut down by 25mm for less weight and more cornering clearance.

Even with the shortest possible piston skirts, the rods are so short the pistons hit the counterweights on the crankshaft.

Remove the counterweights, lighten the crank further and rebalance everything. Carve away at the pistons to cut more weight, thin the skirts to the point of flexibility. Back to AMOL for tool-steel wrist pins. After hours and hours of metal chips flying from the milling machine and lathe, the flywheel and clutch assemblies resemble a carcass picked clean by vultures. But they are light, and just strong enough, and that is all that matters. Pin the flywheel to the crank so that it won’t spin off and move on.

The pistons in the Boxer motors travel back and forth in unison, turning the bottom end into a high-speed air pump. Any blowby past the rings greatly exacerbates the situation. Spend months trying different combinations until a new ring-sealing/break-in procedure coupled with stainless-steel L-section Dykes rings reduces leakage to 2 percent and keeps crankcase pressure down to only a few psi. Take a reed valve from a McCollough chainsaw and use it as a PCV valve. Use a Chrysler Hemi air/oil separator to keep oil fumes from lubing the track. While testing one day, shine a timing light at the base of the cylinders and see them being lifted off the crankcase by the force generated by combustion. Call Liebmann again and have him make up heavy-duty cylinder studs to limit the top end’s imitation of a pogo stick.

Bolt the heads to a Superfio flowbench and prove how awful the stock ports are. Cut, re-angle, weld, carve, build up, shape, polish, flow check, dyno-and repeat over and over until the fuel/air mixture has an easier time entering and exiting the combustion chamber. Drill the heads for a second sparkplug and run one plug at 30 degrees BTDC, the other at 32, because that's what a bazillion hours of dyno time has told you works best.

Replace the oil pump with a smaller unit, reducing frictional losses, eliminating cavitation at high rpm and reducing the likelihood of leaks. Weld a baffle into the oil pan so lubricant doesn’t slosh forward under hard braking and leave the pump sucking wind. Run a large oil cooler upside down to retain oil, thus increasing capacity. A little here, a little there and the Stocker’s 60-horsepower putta-putta-putta grows to the BA WOOOM of almost 100 horses.

Work with Michelin, using new roadrace slicks. Accept the fact that the company won’t make a 19-inch front tire. Spoke up a wide, 18-inch rim and then design a heavy-duty offset top triple-clamp that drops the fork tubes enough to mimic the stock ride height. While you’re at it, have a bunch of triple-clamps made with different angles to suit the tastes of the various riders. To reduce front-end flex, run an additional lower triple-clamp and a fork brace. Order up a corresponding wide slick for the rear and realize how little room

there is on the driveshaft side of the swingarm. Have Buchanan’s drill the rim 5mm off-center to allow the tire to move over to the left.

Next, make up spacers to offset the wheel and carve away at the swingarm to provide as much tire clearance as possible. Use a magnesium rear-drive housing to try to counter some of the additional weight of the larger tire. Inside that housing, stuff a set of taller-than-stock 2.62 gears. While you are on the subject of gears, install the factory close-ratio five-speed cluster, and fit the trans housing with a magnesium rear cover.

Additional power and traction add up to additional torquing of the frame. Lighter weight and more power provide unasked-for wheelies. Move the engine up 15mm for ground clearance and 30mm forward for better weight distribution. Mount the cafe-fairing directly to the frame as opposed to the handlebar where it acts like a big lever when being pushed into the wind at 100-plus mph. Close one eye and read the section in the rule book about “relocating shocks,” then relocate one shock to the parts bin. Brace up the swingarm with a U-section on the top, to which you mount a single Formula One Koni automotive shock complete with adjustable compression and rebound damping. Bolt the shock to the frame and conveniently brace up the frame while making a top shock mount.

As per the rules, use the stock carbs, but bore them out from 38 to 40mm and use velocity stacks instead of the stock airbox. "Stock mufflers," the rules state. Sure, they're stock, but the high priest of motorcycle fabrication, Todd Schuster, hollows them out and places Axtell reverse-cone megaphones inside.

Don't forget the minor details. Eliminate what you don't need: grind or drill holes in

what you have to keep. Remove the double-lip wheel seals and turn off one lip in the lathe to reduce friction. Take the same extreme attitude toward every detail.

And it never stops. At Daytona, despite the new studs, the long hard blast on the banking has the cylinders lifting up enough to allow oil to mist onto the footpegs. Hard to ride when your feet are slipping off the pegs. No time for an engineering solution, so Schuster, with the kind of inven tiveness derived from years of tinkering, makes up sheet metal shields to divert the mist away from the riders' feet. Twenty years later, when a journalist asks, "In preparing for Daytona in `76, who did you see as a major threat to BMW?" answer honestly, objectively. Say, "Nobody."

Armen Amirian is a freelance writer/motorcycle mainte nance instructor at City University New York. Nancy Hoppin provided additional information for this story.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNorton Boy

July 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Deferment

July 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIntake Flow 101

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1996 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Superbike Revival

July 1996 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIs There A Stroker In Your Future?

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron