SERVICE

Paul Dean

Fuel infection

I’m very curious as to why the motorcycle industry hasn’t replaced carburetors with fuel-injection systems. Look at what it’s done for the automobile industry. Could you imagine the improvement in power and throttle response an injection system could have on, let’s say, a ZX-11 or a V-Max?

Jim Bottger Dover, Delaware

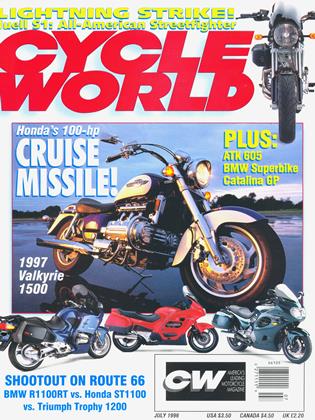

Currently, there are more than a dozen fuel-injected motorcycles on the market (from Bimota, BMW, Ducati, Harley-Davidson and Moto Guzzi), and select Japanese bikes over the years have used fuel injection, dating all the way back to the late Seventies and early Eighties. So, rest assured that motorcycles are no strangers to fuel injection.

But, as you suggest, let s indeed look at what fuel injection has done for the automobile industry. For one thing, it has added considerably to the price of new cars; the total cost of all the injectors, sensors, computers, pumps, plenums and plumbing is a lot more than that of a carburetor. Then there is the significantly higher degree of difficulty involved with repairing a fuel-injection system. Even your average shade-tree mechanic has a fighting chance of remedying most carburetor problems, but when confronted with a fuel-injection system, he immediately enters the realm of the completely clueless—along with most shop technicians who haven’t gone through rigorous EFI training. And, of course, increased repair difficulty and complexity also brings with it proportionately higher repair costs.

What’s more, the automobile industry did not commit to production-line fuel injection to achieve “high ” performance; it was adopted primarily to achieve acceptable performance. Fifteen or 20 years ago, the behavior of carbureted car engines was an embarrassment; hard starting, laughable' power outputs, miserable fuel mileage and Marx Brothers-quality throttle response were standard fare. The precise metering ability of fuel injection alleviated most of those problems while allowing cars to meet the government’s ever-more-stringent emissions requirements.

On the other hand, the overall engine performance of motorcycles has never been better than it is today, even though the vast majority still use carburetors. With very rare exception, modern bikes start willingly, have razor-sharp throttle response and get exceptional fuel mileage, and the performance models make more horsepower than anyone 15 or 20 years ago would have imagined in their wildest dreams. At this stage, at least, equipping them with fuel injection would not embue them with enough added performance to offset the downsides.

And aside from the cost and complexity drawbacks mentioned earlier, there are a couple of others. One is that the types of injection systems best-suited for motorcycles usually have a very limited ability to cope with engine modifications. Try doing much more than slipping on slightly freer-flowing mufflers and you ’ll likely end up with some major tuning glitches that aren’t easily cured. And while the aftermarket usually can supply bigger/better carburetors to complement seriously hot-rodded engines, there ’s no such easy hop-up for a fuel-injected machine. Unless you have the ability to diagnose, reprogram and remanufacture fuel-injection systems, you ’re pretty much stuck with the one that came from the factory.

Fuel injection is neither magic nor a guaranteed route to more horsepower; it’s simply more-precise fuel metering. Motorcycles already have become too complicated for many people ’s tastes. So, count your blessings—and your carburetors.

Chain of events

In Kevin Cameron’s March, 1996, TDC column titled “Torque Shows,” he said that the forces exerted to the rear-wheel sprocket (and, therefore, the drive chain) on a motorcycle are no more than 300 foot-pounds at most. That’s not nearly enough force to cause a drive chain to stretch, since most chains are rated for at least 7000 pounds or more tension capacity. So, if this amount of force is well within the elastic limits of the chain material and could not cause permanent elongation of the chain, can you explain where the force comes from that causes a drive chain to stretch?

Sohrab Navai Chandler, Arizona

First, an all-important fact: Chains do not “stretch.“ Granted, the expression “chain stretch ” is commonly used by motorcyclists everywhere, but that terminology is technically inaccurate. The steel sideplates of a drive chain don’t change their dimensions under heavy loads; the plates may break, but they don’t permanently stretch.

Instead, a chain elongates for two basic reasons. When relatively new, a chain starts growing longer as the original lubricant between the pins and rollers is squeezed or cooked out. And over time, a chain elongates because of wear between those pins and rollers. Even at its worst, the amount of wear at each individual pin/roller junction is very small; but when multiplied by the total number of rollers in an entire chain, usually somewhere between 100 and 120, the cumulative wear can be substantial. Thus, the overall length of the chain increases, which is why it is said to “stretch.” The accepted rule-of-thumb is that when total elongation exceeds 3 percent, the chain is worn out and should be replaced; but some chain experts feel that more than 1 or 1.5 percent of elongation is cause for replacement.

Finally, the amount of force exerted at the rear wheel is much greater than you surmised from Kevin Cameron ’s column. His examples only discussed the amount of rear-wheel torque in top gear; but motorcycles have first-gear ratios that generally range between 2.5 and 3.5 times lower (higher numerically) than those of high gear. So, the amount of rear-wheel torque in first gear actually is much closer to 1000foot-pounds than to 300. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNorton Boy

July 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsTriumph Deferment

July 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIntake Flow 101

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1996 -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Superbike Revival

July 1996 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupIs There A Stroker In Your Future?

July 1996 By Kevin Cameron