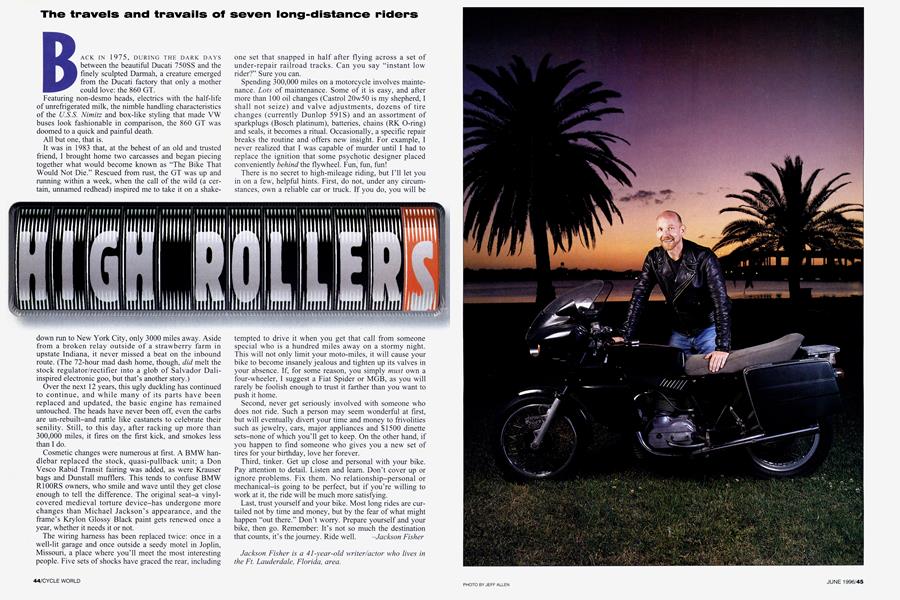

HIGH ROLLERS

The travels and travails of seven long-distance riders

BACK IN 1975, DURING THE DARK DAYS between the beautiful Ducati 750SS and the finely sculpted Darmah, a creature emerged from the Ducati factory that only a mother could love: the 860 GT.

Featuring non-desmo heads, electrics with the half-life of unrefrigerated milk, the nimble handling characteristics of the U.S.S. Nimitz and box-like styling that made VW buses look fashionable in comparison, the 860 GT was doomed to a quick and painful death.

All but one, that is.

It was in 1983 that, at the behest of an old and trusted friend, I brought home two carcasses and began piecing together what would become known as “The Bike That Would Not Die.” Rescued from rust, the GT was up and running within a week, when the call of the wild (a certain, unnamed redhead) inspired me to take it on a shakedown run to New York City, only 3000 miles away. Aside from a broken relay outside of a strawberry farm in upstate Indiana, it never missed a beat on the inbound route. (The 72-hour mad dash home, though, did melt the stock regulator/rectifier into a glob of Salvador Daliinspired electronic goo, but that’s another story.)

Over the next 12 years, this ugly duckling has continued to continue, and while many of its parts have been replaced and updated, the basic engine has remained untouched. The heads have never been off, even the carbs are un-rebuilt-and rattle like castanets to celebrate their senility. Still, to this day, after racking up more than 300,000 miles, it fires on the first kick, and smokes less than I do.

Cosmetic changes were numerous at first. A BMW handlebar replaced the stock, quasi-pullback unit; a Don Vesco Rabid Transit fairing was added, as were Krauser bags and Dunstall mufflers. This tends to confuse BMW R100RS owners, who smile and wave until they get close enough to tell the difference. The original seat-a vinylcovered medieval torture device-has undergone more changes than Michael Jackson’s appearance, and the frame’s Krylon Glossy Black paint gets renewed once a year, whether it needs it or not.

The wiring harness has been replaced twice: once in a well-lit garage and once outside a seedy motel in Joplin, Missouri, a place where you’ll meet the most interesting people. Five sets of shocks have graced the rear, including one set that snapped in half after flying across a set of under-repair railroad tracks. Can you say “instant low rider?” Sure you can.

Spending 300,000 miles on a motorcycle involves maintenance. Lots of maintenance. Some of it is easy, and after more than 100 oil changes (Castrol 20w50 is my shepherd, I shall not seize) and valve adjustments, dozens of tire changes (currently Dunlop 59IS) and an assortment of sparkplugs (Bosch platinum), batteries, chains (RK O-ring) and seals, it becomes a ritual. Occasionally, a specific repair breaks the routine and offers new insight. For example, I never realized that I was capable of murder until I had to replace the ignition that some psychotic designer placed conveniently behind the flywheel. Fun, fun, fun!

There is no secret to high-mileage riding, but I’ll let you in on a few, helpful hints. First, do not, under any circumstances, own a reliable car or truck. If you do, you will be tempted to drive it when you get that call from someone special who is a hundred miles away on a stormy night. This will not only limit your moto-miles, it will cause your bike to become insanely jealous and tighten up its valves in your absence. If, for some reason, you simply must own a four-wheeler, I suggest a Fiat Spider or MGB, as you will rarely be foolish enough to trust it farther than you want to push it home.

Second, never get seriously involved with someone who does not ride. Such a person may seem wonderful at first, but will eventually divert your time and money to frivolities such as jewelry, cars, major appliances and $1500 dinette sets-none of which you’ll get to keep. On the other hand, if you happen to find someone who gives you a new set of tires for your birthday, love her forever.

Third, tinker. Get up close and personal with your bike. Pay attention to detail. Listen and learn. Don’t cover up or ignore problems. Fix them. No relationship-personal or mechanical-is going to be perfect, but if you’re willing to work at it, the ride will be much more satisfying.

Last, trust yourself and your bike. Most long rides are curtailed not by time and money, but by the fear of what might happen “out there.” Don’t worry. Prepare yourself and your bike, then go. Remember: It’s not so much the destination that counts, it’s the journey. Ride well.

Jackson Fisher

Jackson Fisher is a 41-year-old writer/actor who lives in the Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, area.

1952 VINCENT BLACK SHADOW

MILEAGE: 308,000 OWNER: William A. Easter AGE: 60

OCCUPATION: Retired electrical engineer

COMMENTS: “The 1952 Vincent Black Shadow: The name alone can strike fear in a sane man’s heart. Not always being the sane sort, I purchased such a bike for $500 in 1959.

“I’ve since traveled extensively on the Vincent. (Riding overseas was particularly pleasant because Europeans don’t dilly-dally around like we do.) I’ve put 308,000 miles on the bike, although this is an estimate because the speedometer cable and the gears that drive it are the bike’s least reliable parts.

“Of course, this hasn’t always been the case. Other parts have been much more troublesome. In fact, my first trip on the Vincent resulted in a lonely bus ride home. I later discovered that I had burned holes in both pistons because I forgot to set the Automatic Timing Device at full advance.

“I soon found a host of other ‘challenges’ accompanied my Vincent, the most persistent being the repeated failure of the magneto’s fiber pinion. In disgust, I put the bike in storage for about 10 years.

“Off and on, though, I toyed with the black beast. This, and advice from fellow Vincent Owners Club members, was essential to the motorcycle’s subsequent ascension from premature retirement.

“The list of modifications is endless. Suffice to say I have completely rebuilt the engine more than once, and valve jobs are never-ending.

“Which brings up maintenance-the key to achieving 300,000-mile status. Always respect your chain: I try to lube the Vin’s every 1000 miles and replace it every 10,000. Oil and filter changes should be a 1000-mile ritual. Also, I don’t neglect the more routine replacements, such as bushings, bearings, seals and cables.

“And then there are tires. When it comes to destroying rubber, the Vincent stands alone. Originally, I ran a stock Avon Speedmaster up front and Avon Safety Mileage in the rear. After a few too many flats, though, I switched to Avon’s Roadrunner rear tire and have had few problems since.

“Cosmetically, my Vincent isn’t teeming with accessories. I repaint it when I rebuild the engine, and I’ve added Craven luggage, a homemade rack and Stadium bar-end mirrors.

“But I didn’t buy the Vincent for its appearance. I bought it because I love riding it, despite its inherent quirks. And, it’s held up for more than 300,000 miles, something I never expected it to do.

“Not bad for $500.”

1978 BMW R100/7

MILEAGE: 600,000 OWNER: Eugene Walker AGE: 74

OCCUPATION: BMW restoration COMMENTS: “It’s been said that BMW riders are notorious for highmileage mounts. Stories of owners coaxing hundreds of thousands of miles from their Beemers are common. So when I set out to put 250,000 miles on my 1978 BMW RlOO/7, it’s not surprising that I ended up with 600,000. In fact, within the first year I logged more than 95,000 miles on the Slash-7, thanks to numerous rallies and cross-country trips. A similar second season saw the bike’s odometer roll over to the 173,000-mile mark.

“At this point, I realized the time had come for some serious work on the bike. Although I had pulled the heads, installed new rings, and ground the valves at 90,000 miles, the bike had begun to use too much oil, the rear main seal was leaking and shifting had become difficult.

“I removed the transmission and installed new bearings; with the proper shimming, it shifts beautifully. (I replaced the bearings every 125,000 miles to protect the crankshaft, which remains stock.) I honed the cylinders, installed new rings, and ground the valves and replaced the valve seals. I also replaced the leaking rear seal, along with the clutch disc.

“After the repairs, I traveled through Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Florida and other states, for a total of 234,000 miles in 36 months-an average of 78,000 per year in three years. During this time, I began servicing the top-end every 80,000 miles and performing a major engine overhaul every 160,000.

“As a result, the Slash-7 required another full servicing around 400,000 miles, when I completely rebuilt the final drive. As the miles accumulated, later modifications included upgrading the bike’s engine to 1050cc.

“I didn’t neglect the Slash-7’s appearance, either. I repainted the bike, and installed ‘snowflake’ wheels and a Hannigan ST fairing. It also wears a set of BMW saddlebags and a HarleyDavidson solo seat, which provides a more comfortable ride and allows my feet to touch the ground.

“Because the bike is such a pleasant ride, I’ve continued to rack up the miles during the last 20 years, although I never really believed the odometer would read 600,000-but it does. Which means you’ve read yet another story about a BMW owner coaxing an extraordinary amount of miles from his machine.”

1987 HARLEY-DAVIDSON FLHS

MILEAGE: 130,000 OWNER: Allen Cook AGE: 47

OCCUPATION: Photographer COMMENTS: “For some, buying a Harley-Davidson is a life-altering experience. For me, it was more of an enhancement than an alteration.

“Since purchasing my 1987 FLHS five years ago, my wife and I have traveled all over the western United States. And I have found that a simple ride to the local grocery store or the post office has become something I look forward to.

“After 130,000 miles, the Harley’s repairs have almost all been due to general wear and tear, and all the replacements have been stock. For example, the drive belt and sprockets were replaced at 80,000 miles. A new clutch was installed at the same time.

“The starter and solenoid continued to work, even after the odometer rolled past the 100,000-mile mark; however, they too were eventually replaced. The same goes for the ignition module.

“The only recurring complication has been with the base gaskets. They have been replaced four times, although that’s not really unusual if the bike’s mileage is taken into account.

“I’m pleased that I’ve had so few problems because I’d rather be riding my bike than working on it. I handle routine work myself, changing the oil and the other primary fluids every 2500 miles. But when it comes to more detailed maintenance or repairs, I defer to the dealership. Considering the Harley’s record, this system works.

“I originally bought the FLHS with the intention of doing some long-distance touring with my wife, and since our first ride from Mexico to Canada, we have run up 108,800 miles-at least that’s what the odometer read when it broke. Since then, we’ve returned to Canada and taken several more highmileage rides, which is how we ended up with 130,000 miles on the bike.

“After the first few trips, I realized the importance of a trailer, which I immediately purchased and painted to match the bike. I also added a tour pack.

“Because traveling can be demanding on tires, I use stock Dunlop Elite Ils. Although the front is usually good for 22,000 miles, I have to replace the rear every 7000.

“Traveling can also be demanding on the body, which is why I added electric handgrips and wiring for an electric vest. I also took advantage of an aftermarket 2-inch lowering kit at the rear, which allows my feet to firmly touch the ground during stops.

“Over the last five years, repairs and modifications have been few and far between, as opposed to the bike’s proffered excitement, which has been limitless.”

1982 YAMAHA XV920RJ

MILEAGE: 146,000 OWNER: Elliott Iverson AGE: 38

OCCUPATION: Race shop general manager

COMMENTS: “When a magazine compared Yamaha’s XV920R to a BroughSuperior, I thought it was something of a long shot. Nonetheless, I bought a 1982 920 for $1500 and have since run up 146,000 miles on its odometer. In attaining such high mileage, the Twin saw more than its fair share of modifications.

“I first got rid of its flat-track-style handlebar and stock rubber brake lines, but kept the original airbox because I didn’t want the bike looking like an XR750 with its filters hanging out in the breeze. My only addition for a while was a set of Dell’Orto carbs because the bike worked well and, quite frankly, I didn’t know any better.

“Around 75,000 miles, however, second gear refused to engage and the clutch started to slip. After tearing down the engine, I installed a lOOOcc piston kit and a taller fifth gear, cleaned up the ports, and replaced the bad gears and bearings.

“Not too long after that, I discovered the stock front brakes were substandard-the hard way, on the Angeles Crest Highway with the lever pulled back to the grip. I quickly replaced them with FZR four-piston calipers, Ferodo pads and Kosman Racing 12.6inch cast-iron floating rotors. This combination lasted almost 60,000 miles, and would lift the back tire off the road under good conditions.

“As for the fork, I fitted Progressive Suspension springs and modified the damping rods with a RaceTech cartridge emulator kit for an improved ride. The stock rear shock worked fine-that is, after I discovered eight more clicks of adjustment.

“I’ve gone through a number of tires over the years, but my favorites are Bridgestone Spitfire sport-touring S-Ils (110/90-19 up front and 130/9018 in the rear).

“On trips to Monterey, Palomar Mountain and the Angeles Crest, I can usually keep up with my buddies on sportbikes-at least until we hit a long straightaway, where the 920’s lack of power starts to show. To me, it handles very well, although I admit I haven’t had the opportunity to ride a ‘real’ sportbike. Probably a good thing for the 920.

“The motorcycle has been ridden hard since it was purchased. I think oil and filter changes every 2500 miles have kept it going for so long.

“I can’t imagine getting a new bike while this one still works so well. I may be able to run it up to 200,000 miles before I get the desire, not to mention the cash, to purchase a new one.

“It may not hold together much longer, but I’m going to give it a try. Pretty good for a long shot, eh?”

1975 HONDA GOLD WING

MILEAGE: 440,000 OWNER: Allan Zahrt AGE: 39

OCCUPATION: Motorcycle and snowmobile mechanic

COMMENTS: “The potential for accruing high mileage is in the nature of the Gold Wing, what with its almost maintenance-free engine and great ergonomics-which is probably why I’ve been able to log 440,000 miles on my 1975 model.

“I accomplished this by touring all 48 states, Mexico and the southern provinces of Canada. In fact, during the 20 years that I’ve owned my Gold Wing, I’ve ridden an average of 20,000 miles per year.

“I consider myself somewhat lucky because, having spent so much time in the saddle, I have only been in one accident. Not so coincidentally, this resulted in the first of the bike’s cosmetic changes-a Windjammer fairing, followed by a pair of 3-gallon saddle fuel tanks, saddlebags and a tail trunk.

“For additional comfort and convenience, I opted for a bucket seat with a backrest, heated handgrips and a sound system. Solid-spoke wheels provided a more stylish look, as did the bike’s new

1970 TRIUMPH T-120R/T

MILEAGE: 400,000 OWNER: Pat Owens AGE: 60

OCCUPATION: Tool and hardware trade specialist

COMMENTS: “As a mechanic, it’s not always easy to move between the automotive and motorcycling worlds. But I managed it when I went to work for Johnson Motors, the Western-states distributor for Triumph, in Pasadena, California. Because I knew how to make an engine take the checkered flag, I wound up as a mechanic for Triumph factory dirt-tracker Gene Romero.

“When the AMA changed the dirttracking rules to allow 750cc bikes to race in 1969, I knew Triumph would never agree to build a new 750cc Twin unless it proved reliable under extreme testing conditions.

“As an alternative, the company converted a 650cc Bonneville into a 750 and then ordered 200 more for homologation purposes. What would become my 1970 T-120R/T was the first of those original 200.

“Eventually, Triumph did approve the manufacture of a new 750cc Twin and by 1983, the company had produced several touring production crash bars. Most recently, I installed a rear fender and a GL 1100 exhaust system. The latter is one of many mechanical modifications on this Wing. The first was a switch from the stock points-type ignition system to an electronic one, although at 340,000 miles I reverted back to stock because it was cheaper. I have also completely rebuilt the starter, only to later replace it-twice.

“Over the years, the Gold Wing has received its share of rear shocks, timing belts, throttle cables and any number of alterations that fall under the heading of General Maintenance.

“Regular service is imperative, and I have found the bike runs best when I replace the wheel bearings, driveshaft and water pump every 100,000 miles, and the oil and filter every 2500. The motorcycle gets a complete tune-up every 10,000 miles, which is also when I clean the carbs.

“I intend to continue riding my Gold Wing for as long as possible. Although newer motorcycles are nice, I kind of prefer its ride and performance.

“Plus, I’m familiar with this bike. I know it will go 180 miles before I switch to reserve, and the odometer error is 1-2 percent, depending on tires. I also like my

Wing because I can see its engine, which isn’t covered up with a lot of plastic.

“After spending 20 years with this motorcycle, I believe that as long as I can turn the worn, smooth stub that passes for a key and push the start button, 1 will continue to ride my Gold Wing. After all, that’s the nature of the bike.”

Bonnevilles with electric starters. Named the Executive, this motorcycle was offered to me by a friend for $3995 in 1989.

“The temptation was great, but I was happy with my original 120, which 1 had fitted with a Windjammer fairing and a set of Harley-Davidson Sportster saddlebags. I had also installed a Trident oil cooler and Ford truck inline oil filter to make sure the engine would last.

“I haven’t had to deal with a lot of major wear and tear because I constantly maintain the bike. I occasionally change pistons and cylinders to prevent seizure. In fact, the only mechanical problems it has had were a damaged front brake cable and a broken drive chain.

“The latter occurred during a trip to Alaska in 1987. My son was riding behind me down a two-lane road when he passed what he thought was a snake. When he saw me slow down and stop, he realized this snake was actually my chain lying broken in the road.

“Aside from these minor mishaps, the old Bonneville has been a reliable ride. This is probably due to the Formula 3 20/50 Texaco Havoline oil and the KalGard engine protectant I use. I try to change the oil every 1500 miles, and I change the Purolator filter every 3000.

“My secret for keeping the transmission together is a pint of STP. Instead of the gear oil Triumph suggests, I use 140-weight, which is twice as heavy as the manufacturer recommends.

“After putting more than 400,000 miles on my Bonneville, I still ride it daily. Considering we are heading to Alaska again this summer, hitting the 500,000 mark is not out of the question.” U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue