Clipboard

RACE WATCH

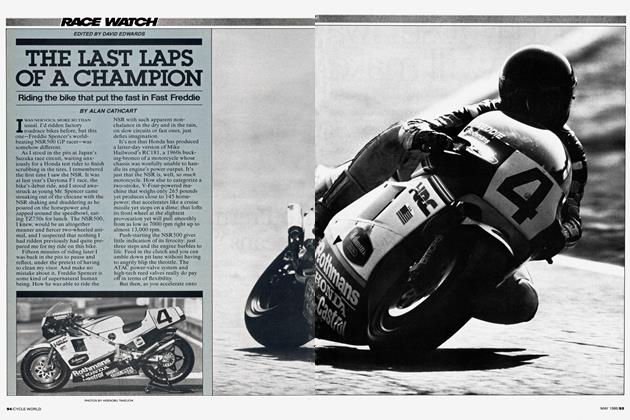

Rainey returns to 500s

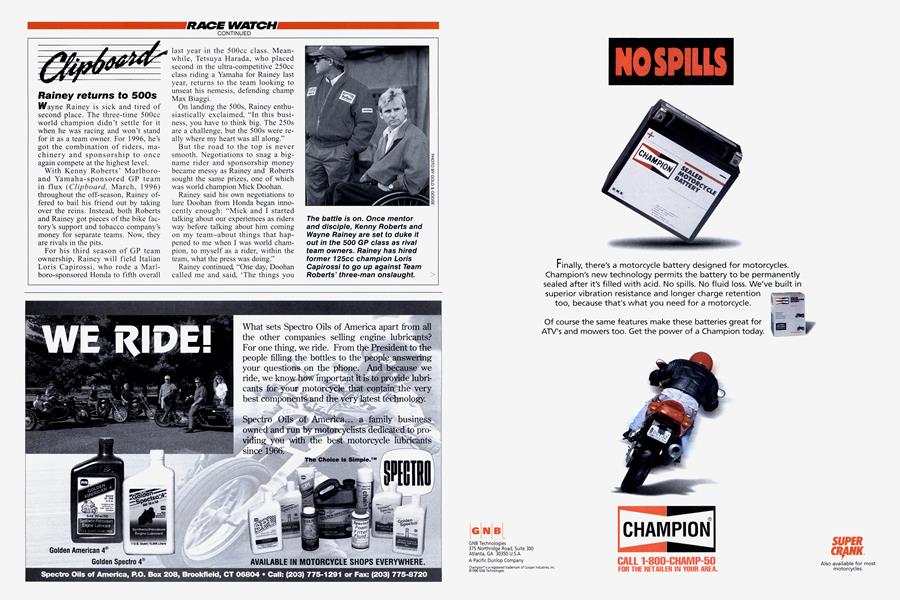

Wayne Rainey is sick and tired of second place. The three-time 500cc world champion didn’t settle for it when he was racing and won’t stand for it as a team owner. For 1996, he’s got the combination of riders, machinery and sponsorship to once again compete at the highest level.

With Kenny Roberts’ Marlboroand Yamaha-sponsored GP team in flux (Clipboard, March, 1996) throughout the off-season, Rainey offered to bail his friend out by taking over the reins. Instead, both Roberts and Rainey got pieces of the bike factory’s support and tobacco company’s money for separate teams. Now, they are rivals in the pits.

For his third season of GP team ownership, Rainey will field Italian Loris Capirossi, who rode a Marlboro-sponsored Honda to fifth overall last year in the 500cc class. Meanwhile, Tetsuya Harada, who placed second in the ultra-competitive 250cc class riding a Yamaha for Rainey last year, returns to the team looking to unseat his nemesis, defending champ Max Biaggi.

On landing the 500s, Rainey enthusiastically exclaimed, “In this business, you have to think big. The 250s are a challenge, but the 500s were really where my heart was all along.”

But the road to the top is never smooth. Negotiations to snag a bigname rider and sponsorship money became messy as Rainey and Roberts sought the same prizes, one of which was world champion Mick Doohan.

Rainey said his own negotiations to lure Doohan from Honda began innocently enough: “Mick and I started talking about our experiences as riders way before talking about him coming on my team-about things that happened to me when I was world champion, to myself as a rider, within the team, what the press was doing.”

Rainey continued, “One day, Doohan called me and said, ‘The things you told me are beginning to happen.’ I told him what needed to be done, and he said, ‘Then, I’ll just ride for you!”’ But ink was never put to paper. As the shoving match for the champ’s services ensued between Rainey and Roberts, Doohan got cold feet and re-signed with Honda.

“When I went after Doohan and approached Marlboro for sponsorship,” Rainey explained, “I did it knowing Kenny already had a contract. I wasn’t looking to take anything away from him; I would never do that. He’s been my greatest friend. That’s the last thing I’d want to do. I said, ‘Hey Kenny, if it comes down to you losing something, I’ll stay home.’”

Always a racer, Rainey defined his new challenge: “Now, we’re competitors. He’s got his team and I’ve got mine. I’m obviously going to try and beat him.”

Ricky Graham, the third coming

“I don’t feel like my career is over yet,” says Ricky Graham, racing enigma. Arguably the most naturally talented flat-tracker ever to strap on a steel shoe, the 37-year-old, three-time AMA Grand National Champion is on the road to the second comeback in his 21-year racing career.

Carrying the weight of the numberone plate in 1985, Graham was unceremoniously dumped from Team Honda after breaking his back and “only” winning four races all season. This led to a dark period where he managed to score just a pair of wins from 1987 to ’92. Graham came back a renewed man and blindsided the competition in ’93, taking the championship by winning 12 of 21 events, and putting a bold exclamation point on his first comeback.

But, once again, resounding success and the burden of being number one led to hard luck and also-ran status. He finished just three races during the '94 season. Graham’s ’95 season was marred by a broken shoulder and then a freak motorcycle accident that landed him in the hospital in a coma.

Graham awoke from his head injury with a new outlook on racing. “I’m just not putting pressure on myself anymore,” he says. “I can’t ride well if I’m not having a good time. After I rode for Honda, I tried so hard that I just couldn’t ride at all. Now, I’m gonna make sure that I ride my bikes a lot, train properly and take care of my life.”

Single and sober after bouts with marital and alcohol problems, Graham has been given a clean bill of health and is now riding motorcycles daily. He’s also well into his training routine, which includes boxing workouts that he says keep his hand-eye coordination sharp. Friend and mountainbiking partner Doug Chandler, who is preparing for his own comeback of sorts on a Muzzy Kawasaki Superbike, thinks Graham is more serious now than ever: “This time around, it seems like he’s putting forth more effort and coming through. I’d say this is the best that I’ve ever seen him.”

On his relationship with Johnny Goad, the man who tuned his bike en route to his ’93 championship and will again spin the wrenches this year, Graham says only half-jokingly, “He doesn’t put the numberplates on the bike until he sees my face at the races.”

If all goes according to plan, Graham is set to eclipse Jay Springsteen as the number-two man on the alltime national winners list, picking up where he left off in 1993.

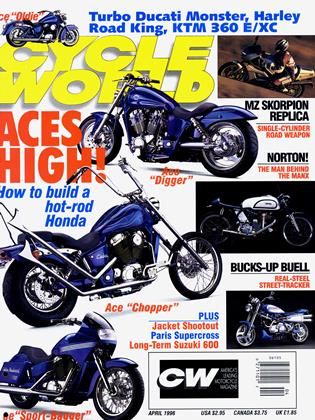

Kocinski “settles” for World Superbike ride

After winning the 250cc world championship in 1990, John Kocinski was touted as the best rider to come out of America since Kenny Roberts. Yet he somehow managed to go from young prodigy to unwanted stepchild in the GP paddock. He sat out the 1995 GP season after failing to find a suitable ride. Over the winter, Kocinski’s name was linked to possible GP deals with Erv Kanemoto’s Honda team, Kenny Roberts’ Yamaha squad and then to the factory Ducati World Superbike team.

Kanemoto, an American who tuned Hondas for Freddie Spencer, Eddie Lawson and Wayne Gardner, has shown interest in Kocinski, but the two have never worked together. With a shrinking worldwide acceptance of cigarette advertising, Kanemoto believes the current sponsorship climate is more favorable to riders who come from countries where smoking is readily accepted. This explains why it was easier to put Italian Luca Cadalora on his Honda NSR500 than Kocinski. “It’s hard to find a sponsor that could benefit from an American rider right now,” Kanemoto says. Cadalora and Kanemoto worked together previously, winning the 250cc championship with a Rothmans Honda.

Once the Kanemoto connection vaporized, Kocinski’s choices were narrowed down to a berth on the Marlboro Roberts Yamaha GP team he left in a cloud of controversy in 1993, or the deal with Ducati. Kocinski tested the 916-based Superbike at the Misano circuit on a cold, wet day and quickly flew back to California. Suddenly, Roberts’ offer was pulled, forcing Kocinski to sign with the Italian marque.

While this doesn’t seem like a happy turn of events, it may be a blessing in disguise for the adaptable racer: Being a big fish in a smaller pond may appeal to his mercurial temperament.

NASB races into second season

The Great American Roadracing Schism is now a year old. In years past, the AMA had left the management of motorcycle roadracing to Roger Edmondson and his Championship Cup Series (CCS) organization. Last year, in a dispute escalating from renegotiation of their respective roles, the two parties split, each offering its own national roadracing series. When all the manufacturers’ Pro racing teams chose to side with the AMA, race promoters who had initially favored Edmondson’s new NASB series followed in their wake. The AMA had won.

Now, a year later, Edmondson’s North American Sport Bike (NASB) series lives on, in a joint venture with Doug Gonda’s Formula USA Series. NASB is preparing to offer a 1996 national championship of nine events for six diversified classes. The familiar CCS regional racing program continues as it has for many years.

Other NASB classes will include EBC Brakes Sport Bike, Mobil 1 Triumph Speed Triple Challenge, Harley-Davidson Twin Sports, Buell Lightning Series and the 125cc International Grand Prix class. The production-based Sport Bike class will use the widely available Dynojet dynamometer to help implement a novel formula based not on displacement, but on horsepower (102 maximum), as well as weight (395 pounds minimum). With peak horsepower de-emphasized, handling and powerband width will become the tuner’s primary tools.

Edmondson commented, “To some we represent an alternative, but to most we’re just a place to race. The racing is there-we just provide the theater. I don’t subscribe to the idea that there’s too much racing.

“More racing,” Edmondson summed up, “can only be good for everyone.”

Harley troubles

America’s answer to the Ducati 916-Harley’s VR1000-continues to suffer in U.S. Superbike racing. The engine and chassis have strong potential, but it has yet to be realized.

The VR is still 15-20 horsepower down on the competition, and the all-powerful Ducati and new 750s from Japan seem ready to pull everfarther ahead.

Four-stroke race-engine design is not a mysterious black art. The VR’s failure to reach horsepower parity with its competition after so many years of development tells us that the engineering process is not taking place.

Reports of a revamped program, with Harley-Davidson Engineering VP Mark Tuttle-long regarded as a major VR supporter-taking early retirement and a new R&D entity called Gemini now pursuing VR development are big news. VR chief Steve Scheibe and his crew of five will now handle only racing operations.

More people means more progress. Race Department PR man Art Gompper assures us that VR1000 status within the Motor Company remains on-track.

Undercurrents disagree. Insiders consider Tuttle’s departure at least somewhat VR-related-although the Motor Company flatly denies this— and Scheibe is said to be under “close scrutiny” because of the program’s problems. Scheibe and his crew have been spread desperately thin trying to simultaneously develop and race the VR.

Does the new Gemini group contain experienced racing R&D people? Will separation of R&D from race operations be enough to leapfrog the VR program forward? The first clear and public answers will appear when Daytona practice begins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue