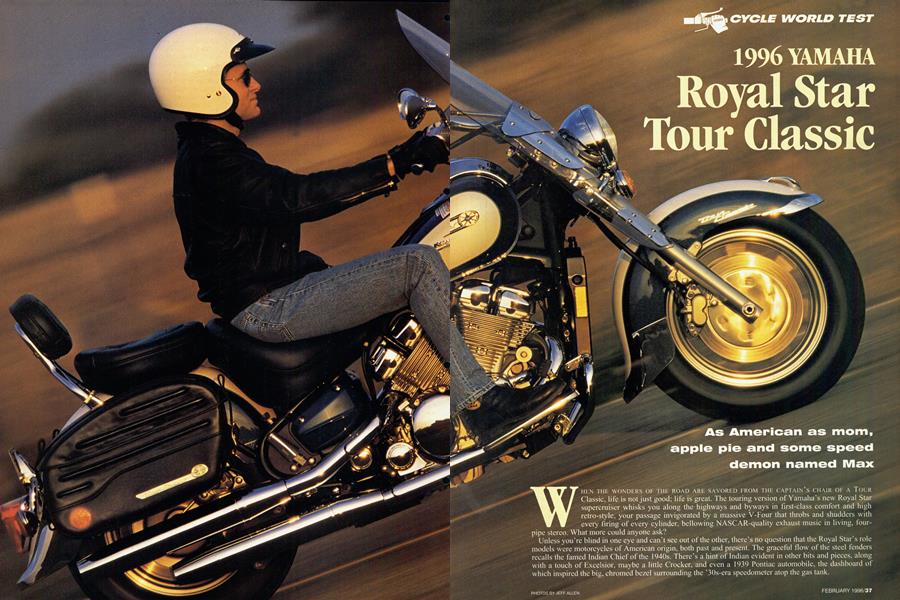

1996 YAMAHA Royal Star Tour Classic

CYCLE WORLD TEST

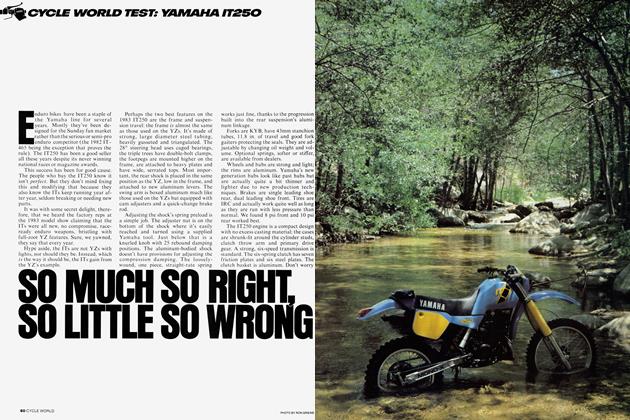

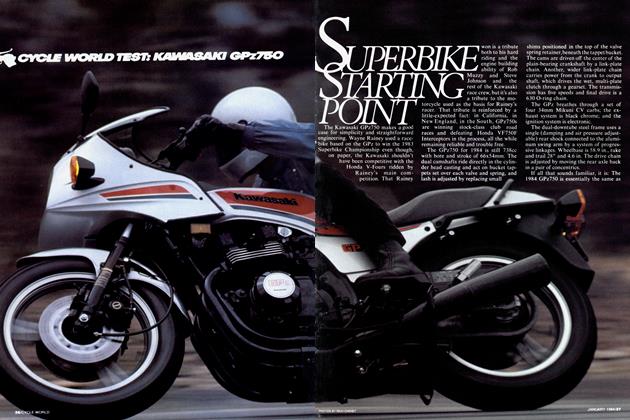

As American as mom, apple pie and some speed demon named Max

WHEN THE WONDERS OF THE ROAD ARE SAVORED FROM THE CAPTAIN'S CHAIR OF A TOUR Classic, life is not just good; life is great. The touring version of Yamaha's new Royal Star supercruiser whisks you along the highways and byways in first-class comfort and high retro-style, your passage invigorated by a massive V-Four that throbs and shudders with every firing of every cylinder, bellowing NASCAR-quality exhaust music in living, fourpipe stereo. What more could anyone ask?

Unless you're blind in one eye and can’t see out of the other, there’s no question that the Royal Star’s role models were motorcycles of American origin, both past and present. The graceful flow of the steel fenders recalls the famed Indian Chief of the 1940s. There’s a hint of Indian evident in other bits and pieces, along with a touch of Excelsior, maybe a little Crocker, and even a 1939 Pontiac automobile, the dashboard of which inspired the big, chromed bezel surrounding the ’30s-era speedometer atop the gas tank.

Obviously, there’s also a lot of current Harley-Davidson in the Royal Star, though its designers insist they never set out to clone Milwaukee iron. It’s virtually impossible, they explain, to build a bike that embodies the spirit and substance of American-style motorcycles without it bearing considerable resemblance to an H-D. After all, as the sole manufacturer of authentic American motorcycles for nearly four decades, Harley-Davidson alone has defined the breed throughout the entire modem motorcycle era. So, it’s no wonder that when seeing a Tour Classic for the first time, most people either compare it to-if not mistake it for-a Harley.

Two H-D models in particular warrant such comparisons. The Tour Classic takes a straightforward approach to longdistance travel by adding to the basic Royal Star only a large, clear windshield (augmented by two small deflectors below the shield, one alongside each fork leg) and a pair of nondetachable, hard-plastic saddlebags; that correlates nicely with the Motor Company’s popular Road King, right down to both bikes’ cast wheels, dual front discs and removable passenger pillions. Yet, the Yamaha’s old-timey visual cues, which include the leather trim on the saddlebags, seem to be speaking the same language as the Heritage Softail Classic.

But while those Harleys share some visual and structural similarities with the Yamaha, the engines are quite different. The 1340cc H-D motor is an ohv, two-valve-per-cylinder, chain-drive, 45-degree V-Twin with roots that go back 60 years; the Tour Classic’s 1294cc engine is based on the same dohc, four-valve-per-cylinder, shaft-drive, 70-degree V-Four

that powered Yamaha’s Venture touring rig between 1983 and 1993. It’s also the same basic engine used since 1985 on one of motorcycling’s living legends, the V-Max hot-rod.

To endow it with a character better suited to cruiser duty, Yamaha gave the engine a top-to-bottom redesign, including one of the most radical examples of detuning we’ve ever seen. Primarily through the use of very mild cams and 28mm carbs (7mm smaller than those on the Venture and VMax), claimed peak horsepower was dropped from around 100 on the Venture and 135 on the V-Max way down to 74 at a mere 4750 rpm (on a rear-wheel dyno, our testbike churned 62.7 horsepower at just under 5000 rpm). Also, engine speed on this tachometerless cruiser is electronically limited to 5700 rpm, a far cry from the 7500/9500-rpm redlines on the Venture/V-Max.

Yamaha’s goals were to give the engine a flat, broad, lowrpm torque curve befitting a big-inch, American-style cruiser, and to keep it revving slowly enough at most speeds that the rider could feel each and every power pulse. To further intensify that throbbing sensation, the gear-driven counterbalancer previously used in this engine was eliminated.

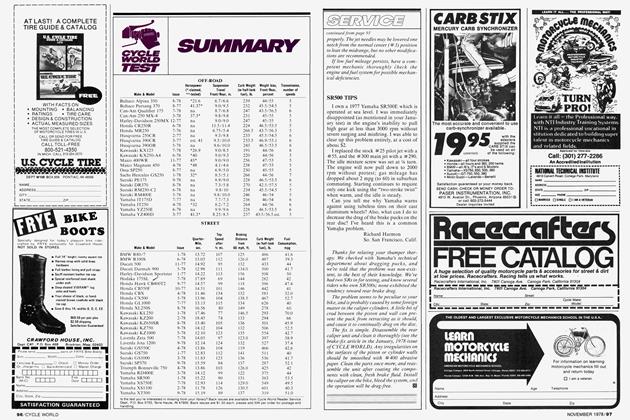

All this might seem like backward engineering, but it actually works rather well. Despite its 758-pound heft-considerably more than either a Road King or a Heritage Classic-the Yamaha lumbers through the quarter-mile in 13.92 seconds at 90.28 mph. That’s not even close to “fast” by any motorcycle standards, but it’s good enough to allow the Tour Classic to outrun either of its H-D counterparts with ease. And although all three manage about the same top speed, the Yamaha’s rollon acceleration is vastly superior, especially above 65 mph.

Still, this engine’s priorities aren’t about power and performance; they’re about sound and feel. And in that regard, the Tour Classic is spectacular. At any engine speed above fast idle, a deep, raucous growl roars out of the four staggered mufflers, a note that sometimes is reminiscent of a Harley’s but that usually resonates with the timbre of a barely muffled Chevy V-Eight. Yet, for all the sweet, loud music the engine plays for the entertainment of its rider and passenger, the noise level heard by everyone else in the area is low and innocuous.

Then there’s the Yamaha’s good vibrations, the low-frequency pulsing in the handlebar, footboards and seat that’s felt with every revolution, every combustion stroke. Although those vibes are omnipresent, the rpm range of the engine is so low that they never become debilitating or annoying but instead are felt only as a pleasant, soothing palpitation.

While revamping the big engine to give it the right sound and feel, Yamaha also gave it the right look. All the outer engine covers were restyled and plated with deep, lustrous chrome. And to make this liquid-cooled V-Four look more like a traditional air-cooled motor, removable fins were bolted onto the outer flanks of the cylinders and heads. Yamaha notes that a secondary benefit of these fins is that they can easily be taken off and painted, chromed or polished without disturbing the rest of the top end.

Surrounding this formidable chunk of engine is a lowslung, stretched-out chassis designed just for the Royal Star. Most noteworthy is the rear suspension, which locates its single shock under the engine much like the dual-shock system on Harley’s Softail models. Yamaha claims such a design was necessary to get the requisite low seat; but the fact that its linkage works the shock “backwards” (extending it as the rear wheel moves upward and compressing it as the wheel strokes downward), just like a Softaifs, is sure to raise a few eyebrows amongst the H-D faithful.

Up front, the Tour Classic looks no less Harley-like, with a big, shrouded fork straddling a fat, 16-inch wheel and a deeply valanced, chrome-trimmed fender. A wide but nicely shaped, 4.8-gallon teardrop tank flows back into a twopiece, stepped seat supplemented by a padded passenger backrest. It all makes for a very big, very long motorcycle, with a 67.2-inch wheelbase which tops even that of H-D’s raked-out, full-custom cruisers.

Nevertheless, the Tour Classic is surprisingly agile at anything faster than a walking pace. It turns into comers much more easily and willingly than you might suspect, and once leaned over, it requires only a light touch to stay on course. Yet, despite its eagerness to change direction, the Yamaha is very stable; it’s unaffected by crosswinds and gusts from passing trucks, and abrupt transitions in road surface have

little or no effect on your chosen heading.

There is a glitch in the handling program, however, caused by a shortage of cornering clearance. To give the Royal Star the desired low-rider profile, Yamaha designed it with vertical ground clearance comparable to that of, say, Harley’s FLS Softail models. But since it is built around a four-cylinder engine rather than a Twin, the Royal Star is significantly wider, meaning that when leaned over in a turn, certain parts hit the ground much sooner.

Indeed, the Tour Classic makes contact with the pavement at shallower lean angles than any production motorcycle to come down the pike in a long, long time. This makes it easy to drag parts of the undercarriage-the floorboards, the sidestand, the engine guards and the lower mufflers-without ever riding aggressively. Even at legal speeds on curvy roads, freeway on-ramps and around city street comers, the alarming graunch of metal against tarmac is a frequent occurrence. The only recourse is to resign yourself to the need to kick waaay back when approaching turns and just cruise around them at a very relaxed pace.

That same chassis lowness also had an impact on ride quality by limiting available suspension travel (a claimed 5.5 inches up front, 3.8 in the rear). Add to that the effects of the bike’s considerable unsprung weight, and the Tour Classic ends up with a ride that’s rather coarse and choppy, although still on the acceptable side of harsh. Besides, the ride is much better than a Softail’s, and is even a bit more compliant than a Road King’s.

Fortunately, much of any harshness that sneaks past the suspension gets sucked up by the Classic’s first-rate seat, a wide, supportive and nicely contoured place on which to park your butt for a few days. Combine this with floorboards that position your knees in a comfortable, 90-degree bend, and a handlebar shape that puts the grips right about where your anatomy wants them, and you’ve got a bike that doesn’t have you flipping through the Yellow Pages in search of a chiropractor at the end of each day’s ride.

While the Tour Classic is not, obviously, a comer-charger, its triple-disc brakes are befitting one. They’re predictable, fade-free and rarely require more than light pressure on the hand lever and car-type, rubber-covered foot pedal. So, too, does the heel-and-toe shifter work meticulously, always responding with ultra-smooth gearchanges.

That kind of sensible engineering is not evident in the placement of the ignition lock, which is tucked below the right-rear edge of the seat. The front of the right saddlebag is so close to the seat that your hand must struggle through a narrow, oddly shaped, hard-to-see opening just to get the key into the lock and turn it. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Smart, smart, smart describes the big windshield, though. It pokes a wonderfully effective hole in the wind that creates a pocket of peaceful, quiet air around the rider’s head and torso. And the little winglets below the windshield noticeably reduce the air blast that reaches your legs.

There’s also a certain road savvy apparent in the saddlebags, which are more spacious on the inside than seems possible from the outside. The bags’ lids are hinged so they can’t fall off or get misplaced, and are secured by a large, easy-to-use buckle on the front and rear of each bag.

What Yamaha has crafted here, then, is an impressive first foray into the world of big, over-the-road, American-style cruisers. With just one notable exception, the Tour Classic is a fine example of the genre: big, torquey, comfortable and stable, with the kind of look, feel and sound that can make you fall in love with it even before it starts moving.

That aforementioned exception is the limited cornering clearance, of course, and it can be worked around. But it seems a shame that Yamaha placed such a needless limitation on an important new model that otherwise does so much so well.

In fact, it does it so very well that even the lean-angle problem wasn’t able to dampen our enthusiasm for the Tour Classic. This is a satisfying, enjoyable, fun ride, no matter if it’s cruising around town, sightseeing on country roads or racking up miles on the interstates. Whether you have someplace or noplace in particular to go, this is one of the most entertaining ways of getting there. □

YAMAHA ROYAL STAR

$15,399

EDITORS' NOTES

I WAS FULLY PREPARED TO DISLIKE THE Royal Star. I mean, a V-Max motor with just half its original horsepres sure, dropped into the most hurnon gous chassis to come along since the Amazonas? It's no wonder I expected my ride through Central California on this beast to be about as much fun as 72 straight hours of watching C-Span.

lioy. was I ott-target! the three con secutive 12-hour days 1 spent in the saddle of the Tour Classic were nothing but pure enjoyment. As I roamed the scenic hills and mountains of the wine country, the big Yamaha was a comfortable, satisfying and surprisingly maneuverable sightseeing platform-not well-suited to fast cornering, of course, but in my laid-back frame of mind, I was able to live with that. And to ensure that things never got too sedate, the big V-motor played a constant exhaust tune that made me feel like I was riding shotgun with Dale Earnhardt. Now, if we could only get this stupid smile off my face... -Paul Dean, Editorial Director

THE 758-POUND ROYAL STAR TOUR Classic, Yamaha’s response to HarleyDavidson’s hugely popular Road King, is powered by a liquid-cooled, dohc, 16-valve, 1294cc V-Four that generates 63 horsepower and 66 foot-pounds of torque.

Excuse me? A quick glance at the spec charts tells me that a loaded-tothe-gills Honda GL1500 Gold Wing SE offers a better power-to-weight ratio, for goodness sake.

Now, I realize Yamaha did not intend the Royal Star to be a power cruiser, but I can’t help notice such a failing in an otherwise fine motorcycle-besides the extreme lack of ground clearance, that is.

Maybe it’s a cruiser thing. Honda made a similar faux pas when it outfitted the Shadow 1100 with a single-pin crankshaft. The resulting American Classic Edition got a stimulating exhaust note at the expense of 15 horsepower and 8 foot-pounds of torque.

Year of the cruiser, eh? Make mine a V-Max, thank you very much. -Matthew Miles, Managing Editor

LOOK, I LIKE THE ROYAL STAR JUST FINE. A little pricey, sure, but it should find a ready audience. It’s a spiffy-looking retro-barge of a bike that pleads to be pointed at the far horizon. You won’t be passing too many bikes (or cars or VW microbuses, for that matter) in the twisty-turny bits, but so what? They make 916s and CBR900RRs for that sort of silliness. Bolt up a quartet of freer-flowing aftermarket pipes (fishtail tips, please), and you’ll have yourself more aural entertainment than a barrel full of NASCAR stockers. Great good stuff.

If I may, though, a quick lesson in the art of the American hot-rod: Given a choice between more horsepower and less, any red-blooded, right-thinking citizen will opt for more. I guess I understand the need to move the powerband about for more of that old-time cruiser feel, but I can’t help wondering what would happen if you open up the Star’s cases and sprinkle a few V-Max parts into the mix.

Sounds like a project bike, no?

-David Edwards, Editor-in-Chief