LEANINGS

Minibike flashback

Peter Egan

A COUPLE OF WEEKS AGO, I WAS RIDING into the big city from our deeply rural home when I came upon a stretch of road with cars parked on both sides. Turned out it was a yard sale. I hit the kill button on my yet-unrestored metalflake-orange eyesore Triumph 500 and climbed off for a look.

It was late in the day, so the sale looked pretty much cleaned out, the remains being mostly mid-’70s Partridge Family synthetic clothing and pieces of furniture with at least one bad leg. What caught my eye, however, was a minibike. Apparently just purchased by a farmer and his son, it was being loaded into the back of a pickup. The kid was beaming.

The minibike had no discernible brand name, but was of the standard early-’60s variety: double-loop frame (rusty), rectangular upholstered seat (duct-taped), gokart wheels and treaded tires, small chrome headlight, canister-shaped lawnmower gas tank, yellow Clinton “Wasp” two-stroke engine with pull cord dangling.

I hate to admit it, but I found myself staring at the minibike with almost the same drop-jawed fascination and wonder as the kid for whom it had apparently been purchased. If this father and son had not been there to buy the slightly tired machine, I would doubtless have bought it myself, after about 0.5 seconds of careful contemplation.

Minibikes of this design are powerful touchstones of my own teen years. They fit into that same class of memorabilia as my Dave Sisler-model baseball glove, which is sitting right here on my bookshelf, or the Boy’s Model 67A single-shot Winchester .22 that (to my wife’s eternal amazement) has hung on some wall of every house in which we have lived.

Honda 50s and other small Japanese bikes and scooters are generally given the lion’s share of the credit for ushering in the motorcycle mania that struck America in the early ’60s, so it’s easy to forget that minibikes also played a part.

The very genesis of this magazine is tied to them.

CIT’s Founding Editor/Publisher Joe Parkhurst ran Karting World during the first boom years of that sport, a magazine that featured much advertising for, and the occasional road test of, minibikes.

Later, following my own (and my mechanically minded pals’) unfolding metamorphosis away from karts and into the more legally roadable world of minibikes and motorcycles, Parkhurst invented Cycle World magazine. He simply recognized what one sociologist has called the latest “mini-virus.” Minibikes were an interim idea whose time had come.

They were to motorcycles what the go-kart was to a sports car; the irreducible minimum, easily produced. Frame, engine, wheels, gas tank, brought together with an appealing shop-class-project simplicity. You looked at them and said, “Of course. Why didn’t we do this before?”

Typical of my entire youth, my own parents were not drawn in by minibikes, nor did they want me spending $125 of my lawn-mowing “college fund” on a diminutive and probably dangerous motorbike. So, of course, I had to build my own.

And so I did and quite successfully for once.

I took a cast-off boy’s 26-inch bicycle frame to a local welding shop and had a flat steel motor-mount plate welded into the bottom of the front loop, and a piece of water pipe welded across the rear seat stay, to hold ball bearings for a reduction shaft (I had built enough stationary, belt-smoking go-karts to understand the need for low gearing).

The engine, a 1.5-horsepower Briggs & Stratton four-stroke washing-machine engine (yes, rural people used to have gasoline-powered washing machines), was borrowed from my dad’s cement mixer and drove a V-belt off its 2-inch pulley back to a 12-inch pulley on the reduction shaft. To the other end of the shaft was welded a small bicycle sprocket that drove a large bicycle sprocket bolted to a 12-inch pneumatic wheelbarrow tire and wheel at the rear. I had a matching wheel at the front. A lawnmower gas tank was slung from the crossbar by metal straps.

No clutch. No brakes. You bumpstarted it and relied on compression • braking to slow down. No twistgrip. A push-pull cable from a lawnmower operated the throttle.

This contraption worked perfectly the very first time I tried it. With its super-low gearing, top speed was only 15 mph, but it would climb steep embankments like a burro. No brakes were needed; closed-throttle compression almost threw you over the handlebar. Fuel mileage was phenomenal. I could ride virtually all day on the 1-quart gas tank by leaning out the mixture for load conditions as I rode, turning a jet on its primitive carburetor.

One grand, green summer, I rode this thing all over Juneau and Monroe Counties on unpatrolled country roads. (My parents required that I remove the V-belt and push it out of town before riding, but were otherwise more amused than disapproving.) I put hundreds of miles on the minibike, even packing a knapsack and spending the weekend with my school friends, the Volzka brothers, who lived on a remote farm.

I doubt I’ve enjoyed any subsequent motorcycle ride more than I did those carefree summer minibike trips when I was 14, wandering the western Wisconsin landscape of red barns, shaded lanes and indolently watchful dairy herds. It was my first real taste of freedom. I could go anywhere, for once, without pedalling, and-more importantly-without asking.

A great machine.

Someday, perhaps, I’ll buy a commercially built one, with real brakes and a centrifugal clutch. Like the minibike at the garage sale. That kid was mighty lucky I didn't get there a few minutes earlier.

But I’m glad I didn’t. Judging from the look on his face, I’d say it’s his summer. In bike ownership, we should always concede to the larger, more powerful dream.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

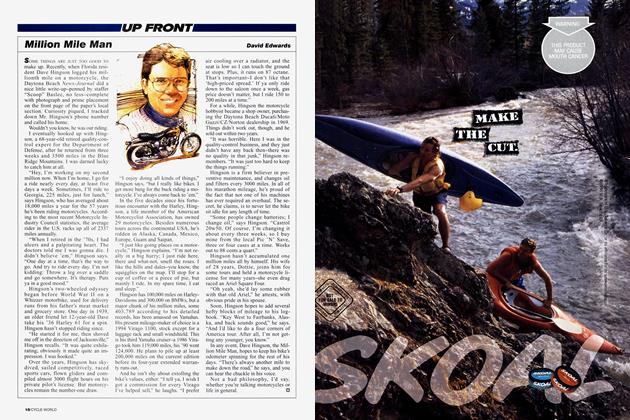

Up FrontMillion Mile Man

September 1996 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCRising Duty

September 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1996 -

Roundup

Roundup1997 Honda Cbr1100xx Super Blackbird Sighted

September 1996 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupSupercross Superbike

September 1996 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

September 1996