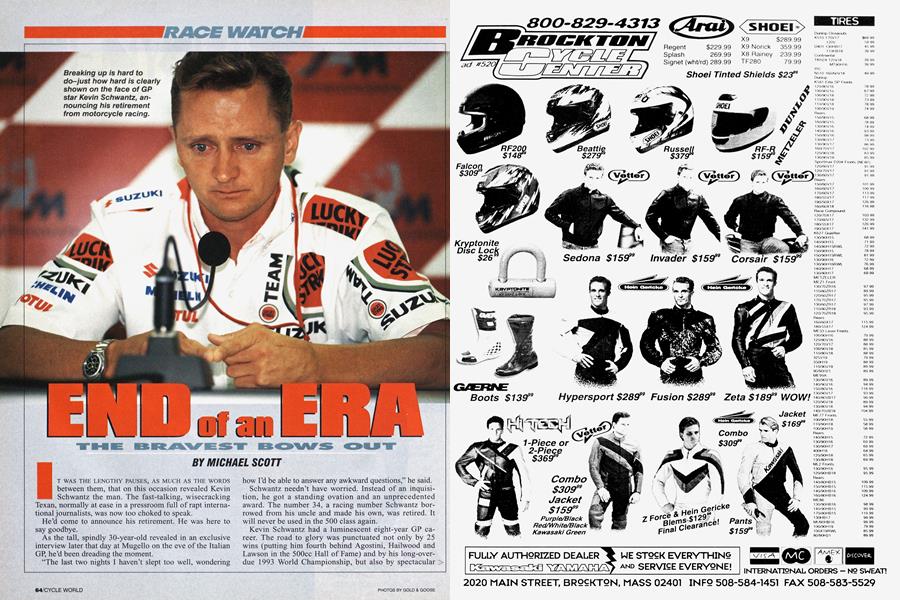

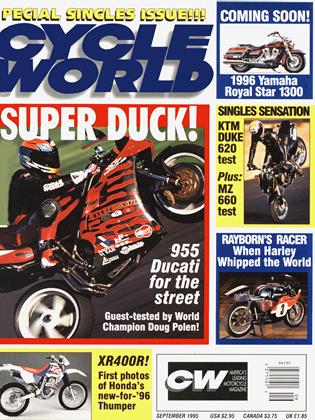

END of an ERA

RACE WATCH

THE BRAVEST BOWS OUT

MICHAEL SCOTT

IT WAS THE LENGTHY PAUSES, AS MUCH AS THE WORDS between them, that on this occasion revealed Kevin Schwantz the man. The fast-talking, wisecracking Texan, normally at ease in a pressroom full of rapt international journalists, was now too choked to speak.

He’d come to announce his retirement. He was here to say goodbye.

As the tall, spindly 30-year-old revealed in an exclusive interview later that day at Mugello on the eve of the Italian GP, he’d been dreading the moment.

“The last two nights I haven’t slept too well, wondering how I’d be able to answer any awkward questions,” he said.

Schwantz needn’t have worried. Instead of an inquisition, he got a standing ovation and an unprecedented award. The number 34, a racing number Schwantz borrowed from his uncle and made his own, was retired. It will never be used in the 500 class again.

Kevin Schwantz had a luminescent eight-year GP career. The road to glory was punctuated not only by 25 wins (putting him fourth behind Agostini, Hailwood and Lawson in the 500cc Hall of Fame) and by his long-overdue 1993 World Championship, but also by spectacular crashes-15 of which involved bone fractures. His stretch of near domination was achieved with a scintillating knees-and-elbows riding style distinguished by fluent-even cavalier-bike control, and by the world’s latest braking. But what more clearly defined the spirit of this most popular of GP riders were the races he rode while injured, shrugging off the pain and the accumulating dread of each slip-gripflick -si ide-scrapc-t umbl e-cru nch-silence to go out and do it all again. end of the main straight by Hondamounted Alex Criville, a good rider, but definitely not one of the greats. “I could hardly believe it,” Schwantz says, “and that was at a corner where I had to regrip the left handlebar three times, because my hand kept rolling over the top of it.”

It was much harder to decide to quit. Schwantz had finally run out of whatever it was that made him keep fighting. And since it had been so hard to justify the decision to himself, he was far from sure of how he was going to explain it to the world.

The decision, Schwantz says, was hastened by his performance in earlyseason testing: “After getting surgery in the winter (on both wrists, while also recovering from a dislocated hip), I fell pretty hard when I first got on a bike to test at Phillip Island in January. Then again at Eastern Creek before the GP, my fastest-ever crash (double piston seizure as he backed off at about 185 miles per hour at the end of the straight). When I stopped sliding, I thought about if I should go back for my other bike, or just go and sit on the wall. I'd had some of the heaviest crashes of my career in the last three or four seasons, and I just wasn't bouncing back like I used to."

It is entirely in character that Schwantz's explanation included only a passing mention of his physical problems. In fact, they were acute. Apart from nagging pain in his right shoulder and twice-separated left hip, his left wrist was close to being crip pled. After suffering dislocations and fractures mid-1994 at Assen's Dutch TT, he'd raced on, even winning one last GP at Donington Park in Britain. But by year’s end the joint was ruined. Drastic surgery had removed three bones. Now it was stiff, painful, and so weak that he was unable to lock his arms in position under braking. He simply couldn’t ride properly. But, as he said at his retirement press conference, “I’ve ridden injured before. The biggest thing was that I didn’t have my confidence any more.”

Braking had always been Schwantz’s strong suit-remember his unforgettable last-lap move on Rainey in Germany in 1991. But at the Malaysian GP this year, he was outbraked at the

Then came the Japanese GP. He’d expected to win in the wet at Suzuka, where he’d won four times before and never finished off the rostrum. Instead he trailed in a dispirited seventh. Confidence again. He says, “Rain was always one of my best conditions. But this time it wasn’t. I never did feel comfortable on the bike.”

After Japan, Schwantz flew back to the U.S. with Wayne Rainey. Schwantz and Rainey had been career-long rivals from the time they first met in AMA Superbike racing. All along, Rainey was better at the consistency that nets titles, while Schwantz was the win-itor-bin-it dazzler. Now good friends, their conversation included the paralyzed former triple-champion’s description of how when he crashed, he had been racing not for his own enjoyment. as always before, but because other people wanted him to race.

“I realized that’s how I felt,” Schwantz says.

There was a two-week break before the Spanish GP, start of the European season this year. Schwantz spent it at home in Texas, with Lucky Strike teammate Daryl Beattie in attendance. But all the while, Rainey’s words, and his own doubts and fears were seething in his mind. Roadracing had been his life since he’d turned professional in 1985. But he’d never not enjoyed it before.

Schwantz explains, “We were due to go and test at Jarama, leaving Monday morning. That weekend Daryl and I and some other friends were going mountain biking. I didn’t go with them.

I stayed at home alone, thinking-do I go, or do I stay? The next morning I was due to pick Daryl up so we could fly to Spain. I showed up without a suitcase, and he said: ‘What’s going on?’ When I told him I wasn’t coming he gave me a real blank stare.”

At his Mugello press conference, Schwantz confirmed that his handpicked young teammate’s successhe’s currently leading the championship-made his decision easier because he wasn’t leaving sponsors Lucky Strike and his care er-long works Suzuki team in the lurch. It also confirmed the bike he’d helped develop over the years wasn’t just a quirky one-rider toy that needed his peculiar talents to make work.

He was further reassured at being replaced by the potentially illustrious Seott Russell who. in difficult circumstances, made a good job of his firstever race on a two-stroke in Italy, placing I Ith after missing one full day of practice and bogging the engine off the line.

“He's the one guy I'm happy to see riding my bikes," says Selnvantz, adding, “I think lie'll he real good, hut he'll take a hit of time to learn. That'll prove just how much of a step up CiP hikes are compared with Superhikes.”

Selnvantz, looking hack on eight years of CiP racing, picked out the worst moment of his career as being told that Wayne Rainey was hurt. This cataclysmic event meant that after having lost the lead in the 1993 title chase after late-season physical problems, he was now assured of victoryhut he only discovered it from a pack of ravenous Italian pressmen who besieged his motorhome in the Misano CiP paddock.

"The other time was knocking Ron Haslam down at the British CiP in 1988." he says. "It was his home CiP and he would have had a real good result. but I ran into him at the chicane on the first lap. it's the only time I ever did that to anybody." This event was to have an echo in 1993, when Selnvantz and erstwhile teammate Alex Barros were skittled in the same corner by an out-of-control Mick Doohan.

Asked about his loyalty to Team Suzuki, Selnvantz says, "I don't regret that I never rode a Honda. I guess I'll go to my grave never knowing what it would he like to ride an NSR. I'd he interested to do it. out of curiosity, hut I don't think the benefits of the hike outweighed the capability of the Suzuki package. We had a hike that wasn't the fastest or the lightest, hut it did most things pretty good."

He selects his career highlights as. “probably my first and last grand prix wins. The first was in Japan in 1988. It was the first GP of my first season. The last was at Donington, one of my favorite tracks. But there’s been a lot of highlights in between.”

As you might imagine, a man as competitive as Schwantz cannot really contemplate a life without racing, and he's already revving up to get onto the NASCAR Super Truck circuit. “It seems like a real good series,” he says. “There’s a lot of bumping and close racing, and they make it good for the spectators. I have the opportunity to test in a Super Truck this weekend-I ran it once already in February, at a little five-eighths-mile oval. But 1 want to take some down time before I rush into anything new. I’ll come to the bike GPs, and be there for the team to help the riders any way I can. If they need some testing done when the other guys can’t do it... maybe I could do that, too.”

It is conventional, when a rider with such an illustrious past comes to the end of his career, to talk about the end of an era. In Schwantz’s case, it is literally true. For the departure of Kevin Schwantz brings to a close a full and uninterrupted generation of American riders who seized the 500 class by the scruff of its neck, starting with Kenny Roberts versus Freddie Spencer in 1983. Only a handful of Australians have been able to offer any opposition.

Kevin Schwantz was not the most decorated of these heroes. But he was always the most dazzling. H i s like may never be seen again. K3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSingle-Minded

September 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Bikes of Lago Di Como

September 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCIllusion, Disillusion

September 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

September 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupNew 900ss Ducks On the Way

September 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupThree's A Charm For Ducati-Ferrari

September 1995