The Short, Sad History of the Hendee Special

IN 1914 INDIAN PIONEERED ELECTRIC START AND SWINGARM SUSPENSION ...AND STALLED PROGRESS FOR 40 YEARS

ALLAN GIRDLER

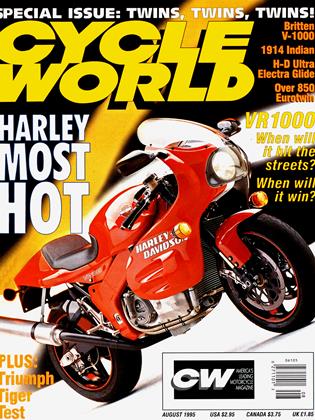

TO SFT THE STAGE FOR TRAGEDY, A quote from the sales literature describing the 1914 models from the Hendee Manufacturing Company, makers of the Indian Motorcycle: "Only the engineering staff which conceived and executed the motorcycle sensation of 1913—the Cradle Spring Frame-could add to that triumph in 1914 a practical, electric system for motorcycle use...They waited only long enough to allow the electric starter and electric lighting to prove themselves on the automobile. Then they undertook the exhaustive work of experimenting, testing, discarding, selecting and evolving Motorcycle Electricity, which has its final and perfected form in the 1914 Indian."

You read that right.

Rear suspension.

Electric starting.

In 1914.

And the result? A disaster so complete and so devastating that both innovations were shoved to the back of the drawing board for another 40 years.

As the rules for tragedy require, the story begins with two heroes, George Hendee and Oscar Hedstrom, the founders of Indian Motocycle, which they spelled that way because in 1901, when they went into the motorcycle business, they could make their own rules.

Hendee was a salesman, organizer and promoter. Hedstrom was an engineer. Both had integrity, vision, courage and intelligence along with their complementary talents.

Both men were aware of the value of value, and of using the best materials and techniques, and-perhaps the most important factor here-they appreciated that if you aren’t moving forward, you're just sitting there.

Indian began with Singles, small but workable engines in what amounted to bicycle frames, and grew into V-Twins in 1906. They didn’t invent the idea, but they made it work. Ditto with features like the twist controls for throttle and spark advance, which they got from Glenn Curtiss and popularized.

Indian fielded a winning race team, in the U.S. and around the world. The make offered brakes and two-speed transmissions and went to chain drive, as opposed to leather belts, as soon as chains were up to the job.

The product was constantly improved, not just in terms of quality but with improvements quick as they could be devised. Thus, Indian came out with electric lights and what the catalog called an “electric signal,” which means the horn, with the system powered by a totalloss battery, the same thing racing machines used years later.

“Step-start”-a Harley-Davidson term, but it’s so elegant it can’t be ignored—rep laced pedals, and Indians offered a front suspension controlled by a quarter-elliptic spring, which, the ads reminded the public, was '"’automotive-type” springing.

This was important. In the very first days of motoring, the motorcycle was a bicycle with an engine and it was a lot cheaper than the horseless carriage and could compete on that basis. Easier on the budget while the car was easier on the body.

But as cars got heaters and tops and side curtains, they also got cheaper. Then they got suspension, in a day when roads were rough or muddy or not there at all.

And then the car got the selfstarter. by consensus the most important improvement ever because it instantly doubled the number of potential motorists, as in women could now venture forth on their own (never mind that not all men were that good with the hand crank and secretly welcomed the starter button).

Hendee and Hedstrom knew that to stay in the game, the motorcycle had to become more useful and comfortable as the car had become easier to buy.

It’s probably not accurate to say they spared no expense because they were practical businessmen and could read the bottom line. But they did do research and they did offer constant improvements: Back in that brochure, the 1914 Indians came with “Thirty-Eight Betterments.”

And they appreciated the appeal of what Sears-Roebuck would call Good, Better and Best. The bargain bike, the Service model, came with the new rear suspension—all the Indians used the same frame—but with a 30.5-cubic-inch Single, the back half of the V-Twin, with pedal start, one speed forward and no lights. Then came the Twins, all 42degree Vees, 61 inches and rated at 7 horsepower with a top speed of 60 mph, surely enough on the roads of 1914. The engine had the exhaust valve next to the piston and the intake valve overhead, IOE as the term goes, with the valves working off a single camshaft in the center of the vee, via a clever and neat system of rockers and levers. It was a good, reliable motor.

There was a racing model with dropped bars and any gearing the buyer wanted, with a rigid rear end, by the way-dirt-track guys were as skeptical about science then as they are now. Then came the Regular-model V-Twin, pedal start and no lights; a Standard model, pedals and lights; the Two-Speed, with transmission and foot clutch; and the two-speed Tourist, with gearbox, lights and that “electric signal.”

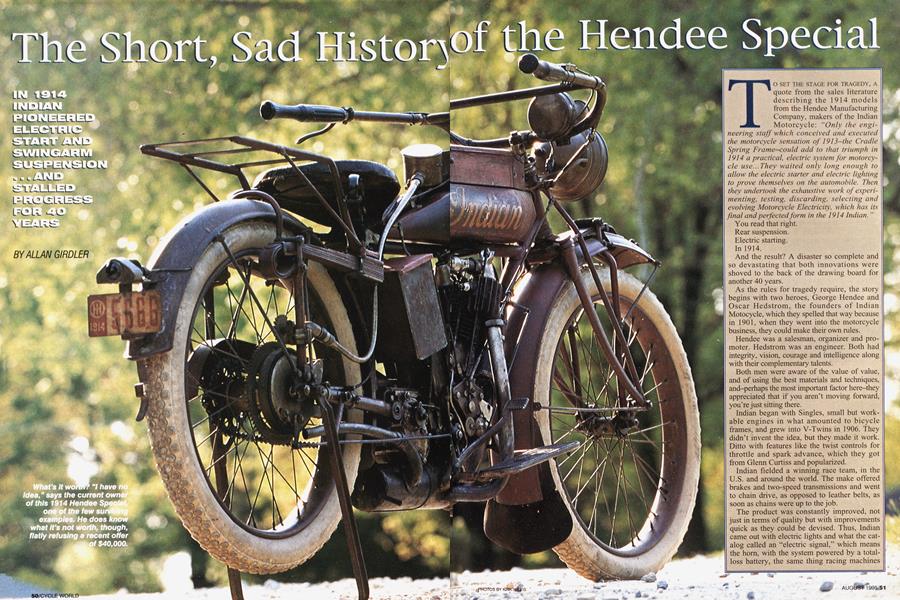

Before we get to the top of the line, two factors: Eirst, check out the rear suspension. It’s uncannily close to

what the world would discover generations later.

The rear wheel and hub are carried in a trailing fork, what would come to be called a swingarm, pivoting from the lower rear of the frame. At the frame’s top rear are fixed a pair of quarter-elliptic springs, also trailing. The springs are linked to each other and to the hub by an upright hoop. This is a neat piece of work, not too far from what HRD had in 1928 and way ahead of the plunger hubs and such the other guyseven Indian in a much later guise-fiddled with in the 1940s and 1950s. It didn’t have damping, but then, neither did the front suspension or Harley’s trailing links.

Nor was this merely an option. As noted, the racing model aside, all the Indians for 1914 offered rear suspension as standard.

The second factor isn’t technical at all.

Hendee and Hedstrom were gentlemen, and in that far-off day a gentleman didn’t feel the need to pile up more moola than Scrooge McDuck could wade through in a week. The founders had seen their opportunity, they'd used their talents and industry and made their mark. In 1914, Indian was the largest motorcycle-maker in the world, with 2500 dealers worldwide, with a manufacturing plant that covered more than 1 1 acres, and with 35,000 in annual sales.

Indian was the biggest and the best, known around the world for innovation and improvement and value. On the strength of that, armed with a graph, so to speak, that went up, up, up, Hedstrom and Hendee were looking forward to retiring to their respective rural estates, to live the lives of country squires and to enjoy their families and the fruits of the hard work...and who can blame them.

Now, the new peak.

The lights and battery parts of Motorcycle Electricity had been pretty much worked out by this time. But for the actual starting system, the founders called in an outsider, an electrical-engineering company.

The collective design departments came up with the round thing at the engine’s left front. It's both a generator and a starter. Inboard of the motor there's a sprocket, and a chain runs from there back to the engine sprocket. That sprocket in turn (sorry) has a double row of teeth, and a second chain goes from engine to gearbox.

The starter/generator was always connected with the engine. No Bcndix drive, no disconnect.

The starter/generator system was built atop the twin batteries of the lighting system, in that the lights drew on one of a pair of batteries and when the lights got dim, the operator sw itched over and made a note to put the tired one on the charger, at home or wherever.

With the addition of the starter/generator, flipping to start mode provided 12 volts, enough when things went right to spin the engine at 500 rpm and start it from cold, the brochure promised, in 12 or 15 seconds, quicker than that when hot. Soon as the engine fired up and began to spin the generator, the switch went back and 6 volts were delivered to each battery, through the additional protection of a regulator.

Sounds pretty good, eh?

All this looked good in the book and performed well during the tests, which brings up 1914.

The system was offered on one model, named the Hcndee Special in honor of the founder, who had 1) been the motivator behind the innovation and 2) was in the process of retiring.

The actual machine, as seen here, was the two-speed Tourist, with lights, gearbox and foot clutch, Indian red with bright parts nickled, the starting system sending the sticker price to S325, compared with $300 for the kickstart model-and, yes, dollars were a whole bunch bigger back then.

We are at the peak of the curve, not that Hendee and Hedstrom had any suspicion of what would come next; in fact, the sales pamphlet mentions that just as Indian production went from 19,000 in 1912 to 35,000 in 1913, sales of 60,000 were predicted in 1914.

What actually came next was a shockingly quick death-and a slow and painful death.

The electric start was virtually dead on arrival. It was, so to speak, too good for this world. In the books and at the lab and, one assumes, during the tests, everything was fine. But the customers didn't take care of their machines, not as carefully as they were expected to, and there were more stops and starts per day, and each start took a few more spins, more time on the button and more drain from the batteries, than predicted. When the engine wouldn't start, there was no backup system. What there was, was unhappy buyers and furious dealers, and-again, one assumes (nobody with us here now was there thcn)-shame and blame in the engineering department.

Historical note: Before anybody snickers at the past, recall that when headlights went on permanently, back in the stone-age 1970s, lots and lots of then-new machines went dead because of the same thing: inadequate charging. The factories first denied it, then told the buyers they should take longer rides and then, there being no choice, made the improvements that should have been there in the first place.

In 1914, a red-faced (sorry again) Indian first handed out extra pairs of batteries, on the theory that owners with lights already had chargers, the hope being that the electric leg could stagger through a day per pair. Wrong.

Then management stopped production, yanked back all the Hendee Specials they could, from dealer floors as well as from customers (see the sidebar for more on that topic), ripped off the big round canister and installed a good of kick start.

Rear suspension died the lingering death.

There were two problems. One, the rear suspension didn't do its job. As with the electric start, when it was brand-new and operating in ideal conditions, the Cradle Frame was smoother and did, quoting the brochure one more time, provide “a sinuous gliding motion.”

But there was wear and tear and neglect, and when it didn't work right, rear suspension was worse than none at all. The bike weaved and sometimes threw its drive chain and it doesn't take much imagination to know what the guys down at the Harley and Henderson stores made of that.

Also, rear suspension didn’t do its other job. The Cradle Frame clearly cost more to make than bolting the rear wheel into the frame did, but the improvement just as clearly was made in expectation of more sales. They didn’t happen. Rather, nobody seemed to care. There were no ardent converts.

The subtle factor in both retreats-and that’s exactly what these were, retreats-was that the men in charge after Hendee and Hedstrom retired weren't committed to the innovations. The founders were motorcycle people as well as businessmen. The new owners were merely businessmen. They were just as honest and probably worked just as hard, but they could see no sense in making a product that was better than the customer wanted.

Thus, they bailed out of Motorcycle Electrics and when new Indians appeared, they had kick starters and rigid rear ends, just as the IOE engines were replaced with sidevalve Singles and V-Twins. They were just about as good, and they were cheaper, and the customers took what they were offered.

If any of this has any import, beyond the chagrin of the folks who designed, built, sold and bought that handful of Hendee Specials, it’s that Indian’s reputation overshadowed Indian’s failures here.

How so? Electric starting and rear suspension were both new, so new that nobody could tell whether the fault in these cases was the idea, or the execution. History, um, make that folklore, blamed the idea. To think that Indian, winner of all those races, biggest factory in the world, could make such blunders would be to believe that General Motors, also largest in the world, would offer a car that fell off the road, or that German engineering brilliance could put the motor in the wrong end of the vehicle.

No, we can't point too sharp a finger. Instead, it’s a matter of record that there was for years and years a consensus that motorcycles didn't need to start easily or ride comfortably and it wasn’t until a challenge from people who didn't know any better that the lesson was learned.

At the same time and even so, one can't help wondering, what if Hendee and Hedstrom had still been at the helm, what if they’d said, “Guys, we’re gonna play this song 'til we get it right?”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOklahoma Hits Home

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsGood Company

August 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThunder Bolts

August 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupBritten To Build Indians

August 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupBikes Will Be Made In the Usa, Says Indian's New Chieftain

August 1995 By Alan Cathcart