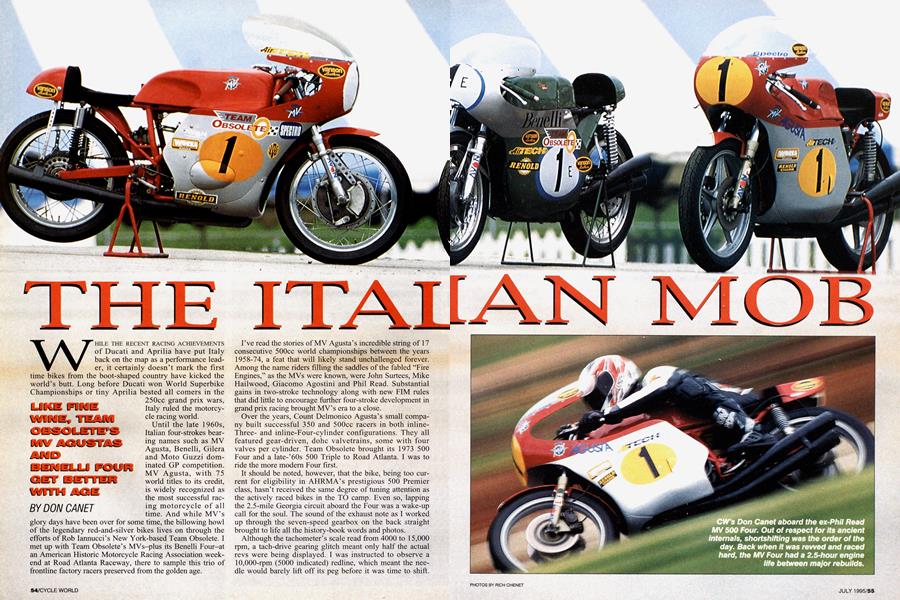

THE ITALIAN MOB

LIKE FINE WINE, TEAM OBSOLETE'S MV AGUSTAS AND BENELLI FOUR GET BETTER WITH AGE

DON CANET

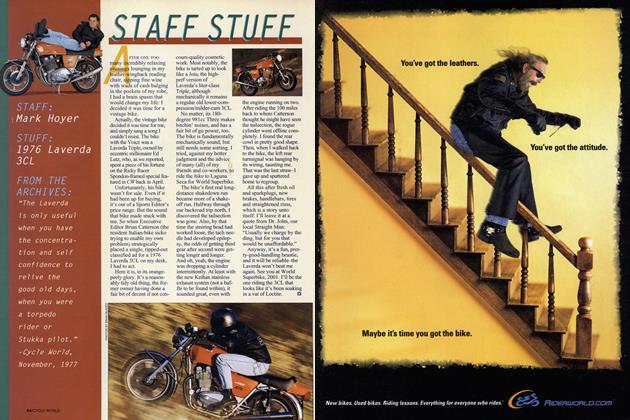

WHILE THE RECENT RACING ACHIEVEMENTS of Ducati and Aprilia have put Italy back on the map as a performance leader, it certainly doesn’t mark the first time bikes from the boot-shaped country have kicked the world’s butt. Long before Ducati won World Superbike Championships or tiny Aprilia bested all comers in the 250cc grand prix wars, Italy ruled the motorcycle racing world. Until the late 1960s, Italian four-strokes bearing names such as MV Agusta, Benelli, Güera and Moto Guzzi dominated GP competition. MV Agusta, with 75 world titles to its credit, is widely recognized as the most successful racing motorcycle of all time. And while MV’s glory days have been over for some time, the billowing howl of the legendary rcd-and-silver bikes lives on through the efforts of Rob Iannucci’s New York-based Team Obsolete. I met up with Team Obsolete’s MVs-plus its Benelli Four-at an American Historic Motorcycle Racing Association weekend at Road Atlanta Raceway, there to sample this trio of frontline factory racers preserved from the golden age.

I’ve read the stories of MV Agusta’s incredible string of 17 consecutive 500cc world championships between the years 1958-74, a feat that will likely stand unchallenged forever. Among the name riders filling the saddles of the fabled “Fire Engines,” as the MVs were known, were John Surtees, Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini and Phil Read. Substantial gains in two-stroke technology along with new FIM mies that did little to encourage further four-stroke development in grand prix racing brought MV’s era to a close.

Over the years, Count Delmonico Agusta’s small company built successful 350 and 500cc racers in both inlineThreeand inline-Four-cylinder configurations. They all featured gear-driven, dohc valvetrains, some with four valves per cylinder. Team Obsolete brought its 1973 500 Four and a late-’60s 500 Triple to Road Atlanta. I was to ride the more modern Four first.

It should be noted, however, that the bike, being too current for eligibility in AHRMA’s prestigious 500 Premier class, hasn’t received the same degree of tuning attention as the actively raced bikes in the TO camp. Even so, lapping the 2.5-mile Georgia circuit aboard the Four was a wake-up call for the soul. The sound of the exhaust note as I worked up through the seven-speed gearbox on the back straight brought to life all the history-book words and photos.

Although the tachometer’s scale read from 4000 to 15,000 rpm, a tach-drive gearing glitch meant only half the actual revs were being displayed. 1 was instructed to observe a 10,000-rpm (5000 indicated) redline, which meant the needle would barely lift off its peg before it was time to shift. Adding to the difficulty was the fact the engine didn't clear its throat and pull cleanly until about the time the tach needle made its move, resulting in a very narrow pie-slice of usable powerband.

While clutch pull was light, shifting action proved sloppy and notchy, with multiple false neutrals ready to catch the complacent foot on downshifts. Another disappointment was the performance of the Lockheed triple disc brakes. A strong three-finger pull at the lever was needed to get the bike slowed, and applying the rear brake didn't help much, either. On a positive note, overall handling was very solid, steering neutral and of average effort.

Throwing a leg over the MV three-cylinder provided a better impression of the Fire Engines’ potential. Raced on a regular basis by Team Obsolete lead rider Dave Roper, the 50ÖCC Triple was ready to do business. It pulled crisply from 5500 rpm to its 11,000-rpm redline and happily accepted full throttle at lower revs, especially after team mechanic Nobby Clark performed a quick air-screw adjustment on the trio of Dell’Orto carburetors to clear up a low-rpm hesitation.

Smooth action of the Triple’s six-speed gearbox allowed concentration to be directed to more important concerns, like the grubbiness of the front twin-leading-shoe drum brake. Its servo action, characteristic of the design, provided excellent stopping power but little in the way of progressive feel.

Virtually every aspect of going fast on a vintage racer requires effort in areas I take for granted on modem equipment. Little details such as a front-brake lever being positioned way too far from the clip-on, or a throttle requiring a good twist (and then some) to get the slides fully open all add up to distraction. No complaints with the Triple’s handling and steering manners, however. It matched the Four in stability and was lighter in feel.

While there were years in which MV faced little opposition on the GP circuit, Benclli did its part to keep the heat on MV following Honda’s departure from grand prix racing at the end of 1967. Indeed, Agostini had his hands full fending off the advances of Benclli factory rider Renzo Pasolini aboard the 350 Four.

When Team Obsolete’s restored Benclli 350 fires, you best have your earplugs in. Whereas the MVs give off a throaty exhaust note, the high-revving Bcnelli-riddcn by Pasolini during the 1967 through ’69 seasons-delivers a forceful shriek from its open megaphones that surely was heard throughout Dixie. Music to the ears! On cold starts, the engine tends to burble and sputter on two cylinders, taking several seconds before it clears itself and hits on all four. Once that happens, it’s a matter of continually blipping the throttle, keeping the revs between 6000 and 10,000 rpm as the engine warms, an exercise that’s nearly as satisfying as the ride itself. There’s little flywheel effect, making for very snappy throttle response. Getting underway, much like on a 250 two-stroke, calls for a fair amount of clutch feed while the revs are maintained around 10,000 rpm. The tachometer needle sweeps counter-clockwise, as if to remind me that, as on the MVs, the shifter is located on the right and has a racer’s reverse-shift pattern. I’m pleased with the feel of the seven-speed gearbox, making easy work of rowing through the ratios-with the change in exhaust pitch my commission. Clutch pull, unncccssary on upshifts, is heavier than that of the MVs; this is more than oil set by the light-action quarter-turn throttle.

I soon learn the importance of keeping the revs above 8000 rpm-that’s if your plan is to drive off corners like a man on something more potent than a Vespa scooter. My first laps are spent shortshifting at 12,000 rpm, but on my final few circuits I reward my senses with the engine's song as it nears 14,000 rpm in each gear, Chin on the tank, tucked behind the mid-height windscreen, all that’s missing is someone to race with. Surely, Roper and the MV Three would be game for a little reenactment of the great Agostini/ Pasolini battles of yore?

With that thought, I begin to realize that the Benclli is pushing all the right buttons, the ones that toggle me into racing mode. Roper and I never hook up, but there’s a wide variety of classic racing machines out in this AH RM A practice session and the little bike just cats them up. The MVs may inspire awe, but I'm completely under the spell of this wailing 350 Four.

I’ve fallen in love with a motorcycle that was built when 1 was 5 years old. And I must admit, handing the green-and-silver Benclli back to Team Obsolete boss Rob lannucci has left a hole in my heart there’s no hope of healing. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter To Willie G., No.2

July 1995 By David Edwards -

Leaning

LeaningNorton Goes To Florida

July 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCHeated Exchange

July 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

July 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupIndians, Yes, But Which Tribe?

July 1995 By Ion F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupNaked Honda Gets A Bikini

July 1995 By Yasushi Ichikawa